What You Need to Know About Calabrian Food

Stefano Caccavari discusses his project, Mulinum.

Image: Alice Levitt

When I told people I was going to Calabria, I was usually met with blank looks. I would staunch the awkwardness with five words: "The toe of the boot." It's the easiest way to explain where I was going—the southwestern-most slice of Italy—but explaining why is harder. In my case, I was headed to speak at NanoGagliato, a nanomedical conference in the tiny, mountainous town of Gagliato, located so to speak, in the instep of the boot. But much of the time, medicine played third or fourth fiddle to food.

The thing that many Americans don't realize is that Italian-American culture is largely Calabrese culture. The bulk of the five million Italians who emigrated to the United States between the unification of Italy in 1870 and America's Great Depression were either Calabrese or Sicilian. Therefore, what we know as Italian food, unless it's specifically Tuscan—remember that vogue in the '90s?—probably has Calabrese roots.

The difference between what we eat and what Calabrians still in Calabria eat is tied to the food system. In the mostly rural region, pasta and pizza come from wheat that's harvested locally and topped with ingredients that come from land or sea that's right there. The best example?

Mulinum

In the town of San Floro, 29-year-old Stefano Caccavari grows an ancient variety of wheat that had long fallen out of favor in a field that was slated to become a garbage dump. Instead, he used Facebook to crowd fund not only a farm, but the construction of a stone mill that grinds the grain to two different textures, one for intensely rustic loaves of bread, another for pizza and pasta. Taste a slice of bread, and you'll be tasting history, fueled by modern technology.

To New Yorkers, this will taste just like home.

Image: Alice Levitt

Pizza Like Home

Thus far, it's been a challenge for this New-York-area native to find a pizza in Houston that's tasted just right. Apparently, I had to go to Italy. In other parts of the country, pies are more like Neapolitan pizzas, or bready Sicilian-style, even if they're not explicitly labeled as such. But I was a moth to a flame once I discovered the pizza at Galatos, the only full-service restaurant in Gagliato. The thin, chewy crust, the even layer of cheese, the acidic sauce, were all exactly what I craved. With prosciutto, corn, Grana Padano and arugula another night, it was a grown-up take on a childhood favorite.

Your new favorite pasta shape.

Image: Alice Levitt

Meet Scilatelle

Not surprisingly, you see as much, if not more, fresh pasta than dry in Calabrese restaurants. This was expected, but what I didn't anticipate was that the prevailing shape was one I'd never seen before. Scilatelli are made with such love that each noodle is careful folded into something that looks like a loosely formed green bean. It's a rare thing to go to a non-tourist restaurant and not see the shape. The above, my favorite version of scilatelle, is served in a tomato sauce with eggplant and chunks of swordfish at Lido San Domenico, the beach in Soverato.

These can make even a teetotaler consider a life as a lush.

Image: Alice Levitt

Farm-Fresh Liquor

I don't drink unless I have to work. But I made several exceptions to the rule at the gorgeous Slow Food restaurant at Azienda Agricola Barone G.R. Macrì. Following course after course of house-made cheese and salumi, scilatelle with stuffed baby eggplant, and potato doughnuts, the finale was fresh fruit and a quintet of liquors also made on the farm. Citruses dominated, with bergamot (the most common local citrus, which tastes something like grapefruit), mandarin orange and lemon. But my favorites were the departures: viscous dark chocolate and strawberry that tasted like the tiny wild fruits that pepper the countryside. The two combined was best of all.

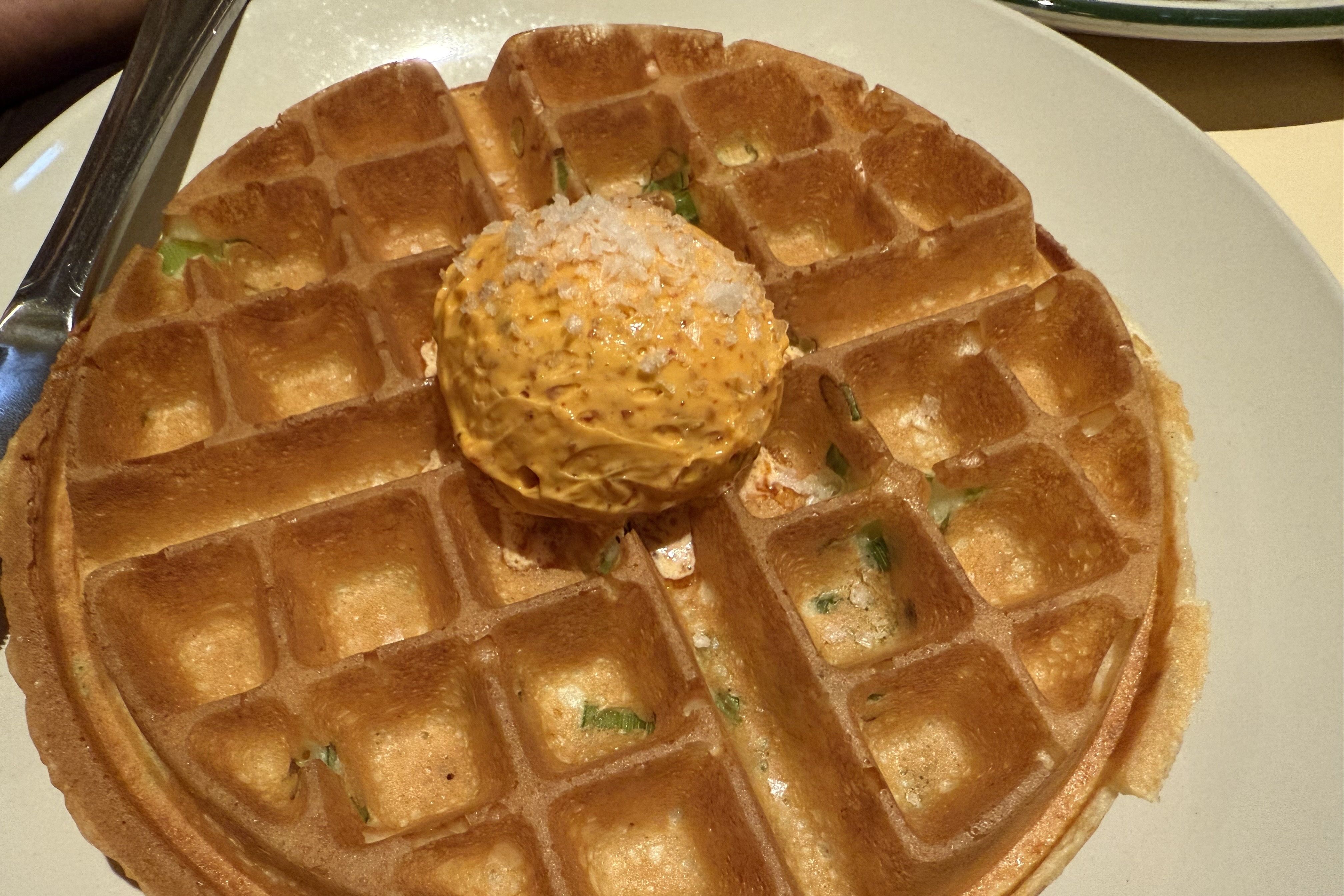

Tartufo di Pizzo isn't the same as the ice cream truffles you'll find at your favorite pizzeria.

Image: Alice Levitt

Real-Deal Tartufo

Most of us have been to a pizzeria and had a layered ice cream bombe (or bomba, if you're going Italian) with a hard chocolate shell, chocolate and vanilla ice creams, and a cherry in the center. When I told Calabrese that this was the American definition of tartufo, they were shocked. The ice cream truffle (the word tartufo means truffle) was invented in the city of Pizzo—as famous for its Piedigrotta, a church carved into the side of a cliff, and the location of the execution of Gioachim Murat, Napoleon's brother-in-law and King of Naples—as it is yummy sweets. Ice cream spots dot the streets there, each claiming to be the inventor of the dessert. My guide recommended Pasticceria Gelateria Raffaele for its dense menu and status as staying in the same family for more than a hundred years. I tried both a pistachio flavor coated in nuts, and the most common version, Tartufo Nero, made with layers of chocolate and oozing chocolate sauce.

Worth a trip on its own? Well, yes. But Calabria's riches are far deeper than just tartufo. There's pizza, too.