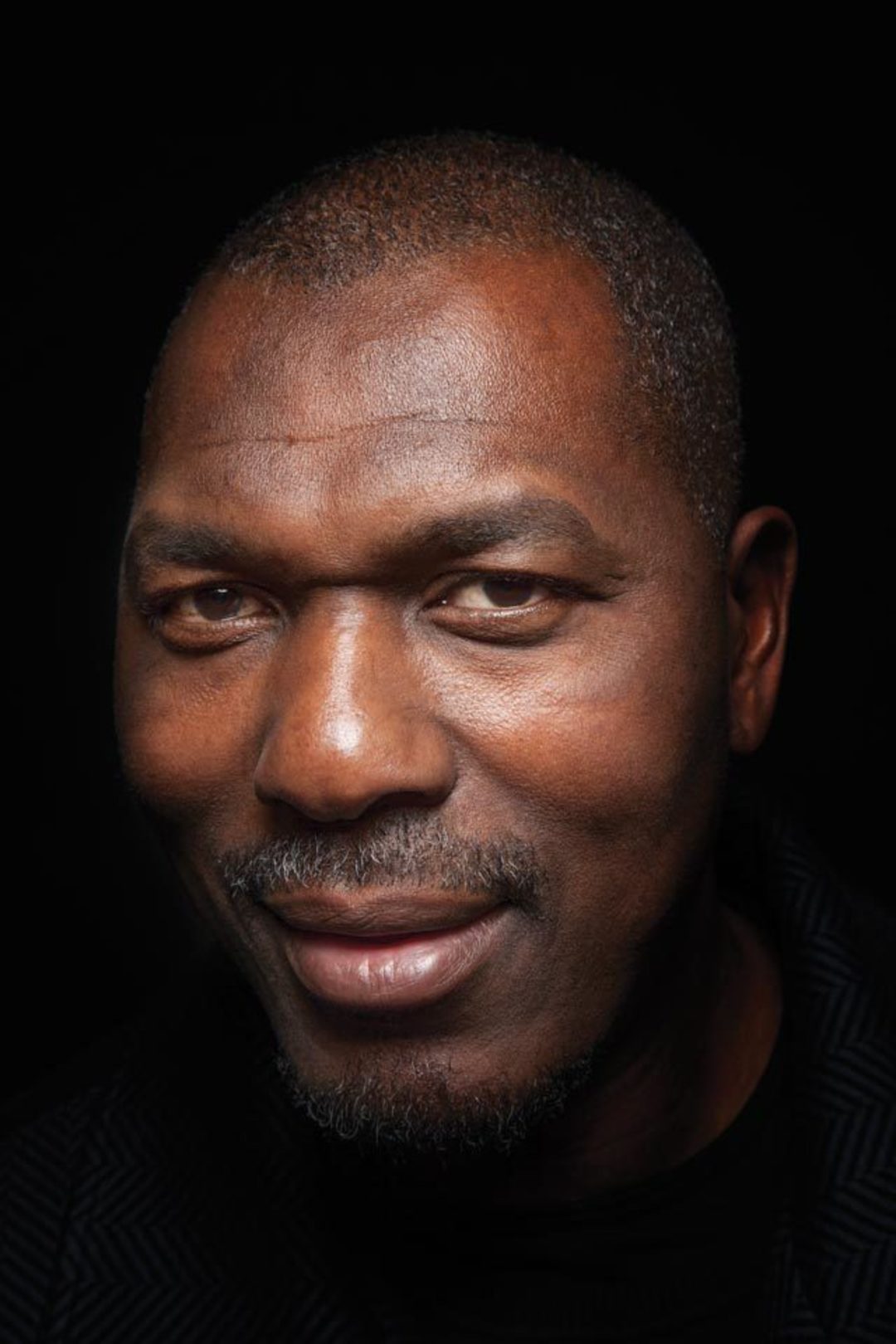

Dream Machine

Hoops Legend Hakeem Olajuwon

Image: Justin Calhoun

It’s safe to say Richmond Avenue along Greenway Plaza has never seen such a sight before or since: a black man in a suit and a white man without a shirt do-si-doeing in the intersection surrounded by a joyous, cheering crowd. The day was, of course, June 22, 1994, and the Houston Rockets, led by six-foot-ten Hakeem Olajuwon, had just beaten the New York Knicks to secure the first championship for Houston in the modern sports era. Thousands of ecstatic fans were pouring into the streets around the Summit. While other cities rioted after their teams’ victories, we danced.

The road to June 22 began many Junes earlier and can be traced to the day in 1980 when a skinny Nigerian teenager first stepped off the plane at Intercontinental. Houston was a boomtown on the brink of an oil bust then, and it wasn’t the happiest of times. Unless you were Hakeem Olajuwon.

“I saw this beautiful drive, beautiful oak trees, great architecture,” he says, recalling the day he arrived at the University of Houston campus to play basketball for the Cougars, then adding something you don’t often hear: “The weather was very nice.”

Almost thirty-four years later, the greatest number 34 in Houston sports history, now 50 years old, is still here, although he splits his time between this city and Amman, Jordan, where his children study Islam and Arabic. Even after a celebrated college ball career, two NBA titles, an Olympic gold medal, and induction into the basketball Hall of Fame, his special enthusiasm for Houston and passionate work ethic remain.

As evidence, consider Olajuwon’s high-end menswear, sportswear, and luxury leather goods clothing brand DR34M and its flagship store in Clear Lake City, housed in the 17,000-square-foot historic West Mansion that sits on tree-dotted acreage just steps away from the lake itself. In the process of opening his store this year, he’s also rescuing a beloved 1929 landmark that neighbors once feared would be demolished. They needn’t have worried. He recalls seeing the massive red-tiled Italianate villa and thinking, “I can’t tear this down.” Olajuwon might be a real estate man—that’s how he’s made most of his post-basketball fortune—but he’s one with a clear aesthetic bent.

That’s fitting for a man who, during his 18 seasons in the NBA, brought matchless creativity to his job as Rockets center, most famously during a legendary performance against the San Antonio Spurs and league MVP David Robinson in the 1995 Western Conference Finals. Olajuwon obliterated Robinson with eye-popping twists and turns, although he is quick to point out that he wasn’t motivated by sour grapes (Olajuwon was the player Robinson had bested for that MVP trophy). Rather, his performance was a kind of modern dance necessary to better his opponent. “You had to be creative against him to get your shot off,” he says. “He forces the creativity to the highest level.”

So it wasn’t a grudge match? “There’s no way to convince people that wasn’t my motivation,” he says with a laugh, adding, “We were in the Western Conference Finals. Why did I need motivation?”

Art, aesthetics, creativity—is it any wonder that the most athletic big man in basketball history is fascinated by the way things look and feel? “I love design, architecture, the feel of certain rooms,” he says simply, by way of explanation.

In person Olajuwon appears quiet, devout, even a bit shy. His disposition created a kind of mystique that lives on among Houstonians and his former teammates.

Robert Horry, Mario Elie, Sam Cassell, Kenny Smith, and Matt Bullard all heap praise on the Hall of Famer, speaking in almost reverent tones. The most common response when hearing his name is a smile and a shake of the head.

Horry says Olajuwon largely ignores the media: “He doesn’t let them inside his world”—which is odd, because in press interviews he is often at ease, engaging, funny even. And he isn’t as reserved as you might think. “I’m quiet out of respect,” says Olajuwon. “Part of being civilized is to respect everybody’s space.”

Perhaps Olajuwon’s most ardent supporter is Clyde Drexler. The two men were teammates both at UH and in the NBA, and Drexler remains one of his dearest friends. “As we grow together, we continue to have this high regard for each other,” says Olajuwon.

Olajuwon did a lot of growing himself during his early NBA years, a tumultuous roller coaster ride of massive successes, crushing defeats and fights both on the court (with opponents) and off (with management). He was a spectacular but undisciplined player. Then, in 1991, Olajuwon devoted himself to Islam, changing his name from Akeem to Hakeem. Everything began to change.

“Before, I got in a lot of fights.” Roughing him up was part of other teams’ strategy, he says, “and I retaliated.” With stronger self-discipline he attributes directly to his faith, Olajuwon learned to dominate his opponents with skill, not intimidation. His game flourished as he evolved into a transcendent star, and the Rockets’ fortunes followed, owing, he says, to the “sincerity of teamwork.”

Olajuwon's work and charitable pursuits keep him busy, as does his family in Jordan, including eight children ranging in age from 2 to 14. But he remembers keenly how it all began, just before a pickup game at Hofheinz Pavilion on his first day in Houston, when a group of varsity players he coaxed into letting him on their squad replaced him before he could get on the floor.

“I got cut from that team,” he says, still sounding incredulous after all these years. Luckily for generations of Houston sports fans, legendary coach and mentor Guy Lewis, watching from the stands, intervened. “All of a sudden, they called me back. They wanted to see me play.”

Now Olajuwon himself is a mentor, offering advice to young players like LeBron James and Carmelo Anthony the way Rockets center Moses Malone once mentored him at Fonde Rec Center. And he still loves the game as much as he did as a teenager in Lagos, even playing pickup games with “regular guys” on occasion.

“I started playing for the love of the game, made a career out of that,” Olajuwon says. “I didn’t leave the game to where, ‘I finished basketball and that’s it.’ I finished professional basketball.”