From Refugee to Jewelry Mogul: Daniel Dang's Rise in Houston

Image: Anthony Rathbun

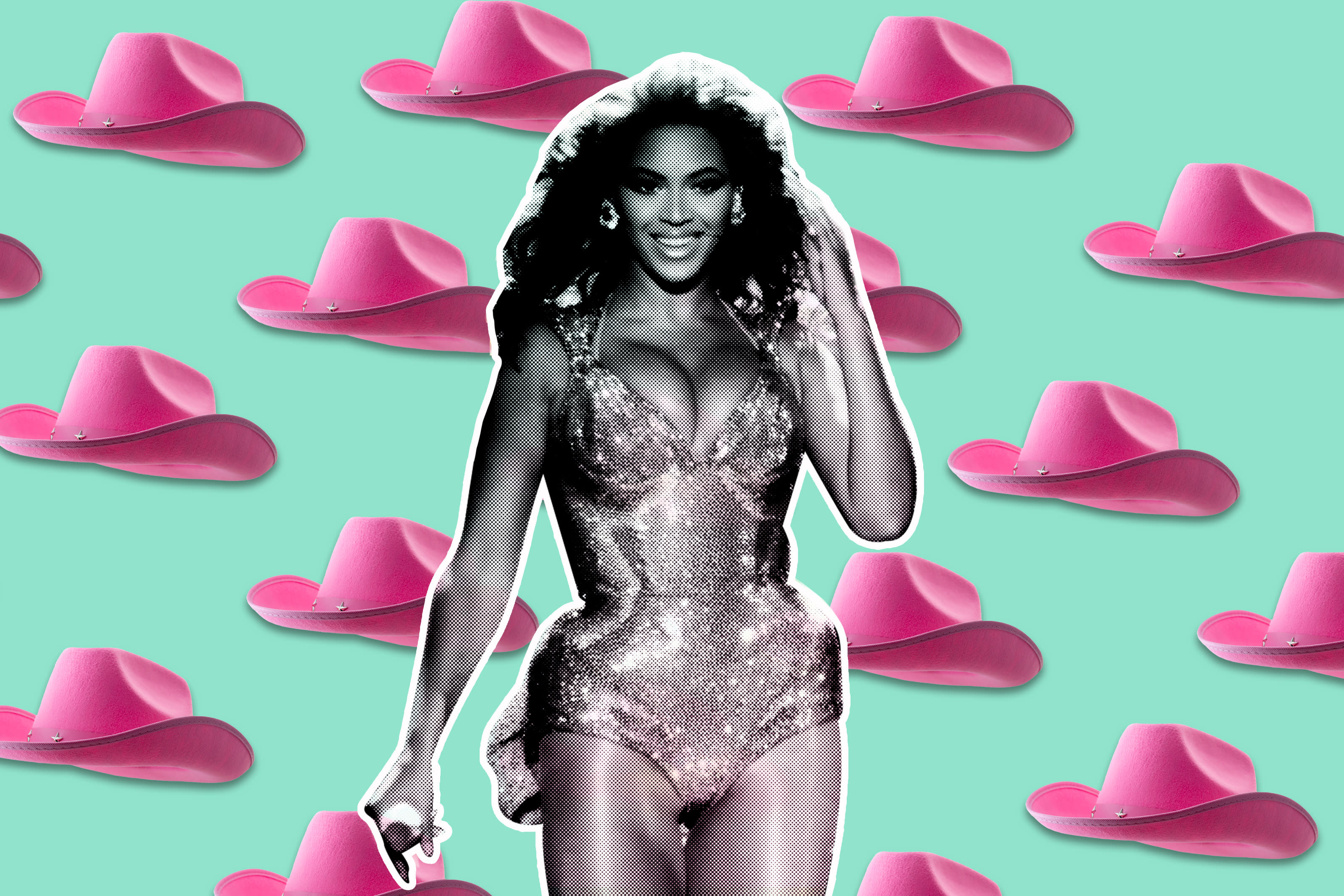

Every bona fide Houstonian knows Johnny Dang. The Vietnamese jeweler is credited with customizing grills, platinum and gold custom mouthpieces blinged out with diamonds, for stars like Paul Wall, Megan Thee Stallion, Cardi B, and Beyoncé. Lesser known, however, is his brother Daniel Dang, who paved the way. As the eldest child of a long legacy of jewelers, Daniel’s rise in Houston is a full-circle moment, not just for him, but for his entire family.

Glittering gems reflect tiny rainbows on a jewelry box as Daniel Dang reaches in, picking up a platinum diamond ring. “When I go to Vegas, I go all out,” Daniel says with a chuckle as he drapes iced-out bracelets on his wrists. After tucking the jewels back into a safe box, Daniel leans back in his chair, taking in all that he’s built. His office, located along bustling Bellaire Boulevard, is filled with luxuries fit for, well, a jeweler. Photos of diamonds, designer watches, and framed copies of Daniel’s work certifications from the Gemological Institute of America hang on the walls. But before the glitz and glam, before he became one of Houston’s premier jewelers, Daniel’s journey was filled with strife, hustle, and war.

The oldest of four children, Daniel, legally Hoang Xuan Dang, was born and raised in Vietnam during the 1970s amid the contentious war between North and South Vietnam. Just five years after his birth, on April 30, 1975, Saigon fell and was overtaken by the communist-led North Vietnam. Daniel’s father, Thomas Dang, who had worked for the CIA, the US military, and the South Vietnamese army, was captured as a prisoner of war and thrown into a prison camp for the majority of Daniel’s childhood. Daniel recalls visiting his father in prison twice. Homelife was also challenging. Daniel remembers destroyed houses in his neighborhood, losing family members to war, and being so poor that his mother sent him away to live with relatives to lessen the financial burden.

But Thomas, though imprisoned, had a plan. “My dad knew under the Communist regime, I [would] never, ever have a future at all,” Daniel says, and so Thomas plotted a way for Daniel to escape Vietnam. The first attempt, which occurred when he was around 8 years old, “fell [through],” says Daniel, who recalls being chased and shot at as he “ran through the jungles, waters, ocean, rivers, try[ing] to hide.” Eventually, he was captured and imprisoned for three weeks before he was released.

Several years later, Thomas planned another escape. Following his dad’s plan, Daniel, then 12, swam roughly two miles into the ocean with a group of 17 other children. A small boat picked up the group, then left them on a deserted island before resuming their journey on another, larger boat days later. Daniel remembers thinking the boat wasn’t large enough to hold everyone, but he and the other children still rushed on, eager to get someplace safe. In the chaos, Daniel fell and injured his leg. Bleeding, he made it onto the boat, where he and the others still risked being captured. Some of the older children pretended to be fishermen to hide from coastal patrollers. “If they catch you escaping the country, they’ll kill you,” Daniel says.

After three days of sailing, the group entered international waters, but that was only half the journey. The boat drifted aimlessly through the ocean, its crew waiting for someone to rescue them. “There’s no food, there’s no drink, there’s no gas,” Daniel recalls, so the crew survived off of the occasional fish, rainwater, and during the most desperate times, whatever dead things floated to the surface in the ocean. Daniel even drank his own urine several times, mixing it with saltwater and toothpaste to make it more appetizing.

Image: Courtesy of Daniel Dang

Meanwhile, Daniel’s leg injury worsened. He fell in and out of consciousness, teetering on the brink of death as the tiny boat, too small for the dozens of passing cargo ships to spot, drifted. He listened to the whispers onboard. Boatmates were waiting for him to die so they could eat him. “Oh, s—, oh hell no, you’re not gonna eat me!” he recalls thinking. But he feared this would be his end. He apologized to his mother aloud, expressing his regret for leaving home. “There’s nothing else you can do, right?” he says. “You just wait and die.” Then, the unthinkable happened.

A boat filled with Filipino fishermen rushing to shore stumbled upon the crew. The men rescued them, bringing them to a small island on the edge of the Philippines. Had they stayed in the ocean for another 30 minutes, an incoming storm would have wiped them out, he was told.

Weak and emaciated, Daniel crawled onto the beach and chugged water from a bucket. “I can’t even express the feeling,” he says.

That island served as Daniel’s home for the next several days before the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or the UN Refugee Agency transferred him and the other children to the Palawan Refugee Camp.

Life there was different. “Basically, you’re on your own,” Daniel recalled. People who lived in the camp, which was divided into zones, shared mud homes with straw roofs. Daniel, who lived among other single Vietnamese refugees, says in some ways, conditions were better. Food and water were more abundant. People would gather at a local temple and church, and he remembers playing soccer with other children, taking English classes, and watching Jackie Chan movies during the occasional weekend movie night.

Image: Courtesy of Daniel Dang

All the while, he and the other refugees dreamed of being sent to America. Two years later, Daniel was the first in his immediate family, and one of the few in his camp, to be granted refugee status in the United States. He came to Houston as a young teenager in the early 1980s to live with an aunt and uncle who had fled Vietnam years before him. Daniel acclimated to life in Alief, attending local schools like Elsik and Hastings high schools, but learning English, even through the ESL programs, was challenging. It was also a culture shock. He thought, “Why are you talking so fast? What kind of English is this?” Alief schools felt like a “five-star hotel.” “Back home, all schools [are] in the jungle,” he says. “There was no school.”

Still, Daniel excelled. He became fluent in English and worked odd jobs after high school to support himself. He waited tables at Vietnamese restaurants, served as a cook at local fast-food joints, sold security systems door-to-door, fixed cars at a mechanic shop, and even worked on the assembly line at the old Igloo coolers factory in West Houston—but it wasn’t enough to thrive.

In search of success, Daniel left Houston in 1987, bouncing around New York and California with friends. He landed a part-time gig at a flea market, widely known as a “swap meet” in California, where a jewelry store owner paid him $20 a day to set up and take down his stand. The owner taught him about the finances when things were slow. That’s when Daniel learned that the jewelry business was the most lucrative industry he had worked in.

In 1988, while still in California, Daniel got word that his father was free after making a successful escape from prison on his third attempt. With a bouquet of fresh flowers in hand, Daniel met Thomas at the airport. It was the first time they had seen each other since Daniel was a child. “It was very emotional,” Daniel says.

Daniel moved his father into his home, which was then half of a literal garage. “I [couldn’t] afford a whole garage,” he says with a laugh. “To me, it was fancy compared to the refugee camp.” After six months, they split up again to pursue their own careers. Daniel returned to Houston and delved into jewelry making. In 1991, he opened his first company, Daniel & Co., with two friends, leveraging six credit cards and borrowing $30,000 from acquaintances to establish a tiny stall in Sharpstown. They later opened another stall in a local flea market, which also offered jewelry repair and design.

Image: Anthony Rathbun

Daniel admits that the earliest designs were ugly and boring, crooked and unpolished. “Oh, my God, it [was a] disaster,” he says. But they were his. They were handmade, and they became a foundation that would help support his family.

Around 1996, Daniel’s mother and his three brothers—Kevin, Johnny, and Jimmy—were granted refugee status. The family reunited in Houston with Daniel and his father and quickly began working with Daniel at the flea market. Daniel’s brothers launched a business of their own, which would later expand into making their own signature grills (Johnny Dang launched TV Jewelry in 1998 and later went into business with local rapper Paul Wall). Daniel continued to customize jewelry and grow his business, Daniel & Co., which he’d later learn was in his bloodline: His great-grandparents had been jewelers for the Vietnamese royal family. Generations before him, the Dangs, including his father, uncle, and aunt, all worked for Vietnam’s leaders, crafting dazzling jewelry literally fit for kings. Returning to the family business was fate.

These days, Daniel runs the Bellaire Boulevard shop, drawing up new designs and creating glamorous one-of-a-kind pieces. His work has been showcased in high-profile events around the city, including the All-Stars Car Show, for which he encrusted the All-Stars trophy with 10,000 diamonds. Daniel also acquired Kim Chung Jewelry, a business located near Daniel & Co., to expand his footprint. Additionally, he hopes to expand his company through franchising.

Daniel realizes how far he’s come. “We always dream. We always want to dream [big] like this,” he says, looking around his office, remembering the days when his goal with his Sharpstown stand was to make a living. “It was too big [of a dream] for me, especially when you have nothing.” With his company, he’s exceeded his wildest expectations, but “I don’t think I’ve achieved anything yet,” he says.