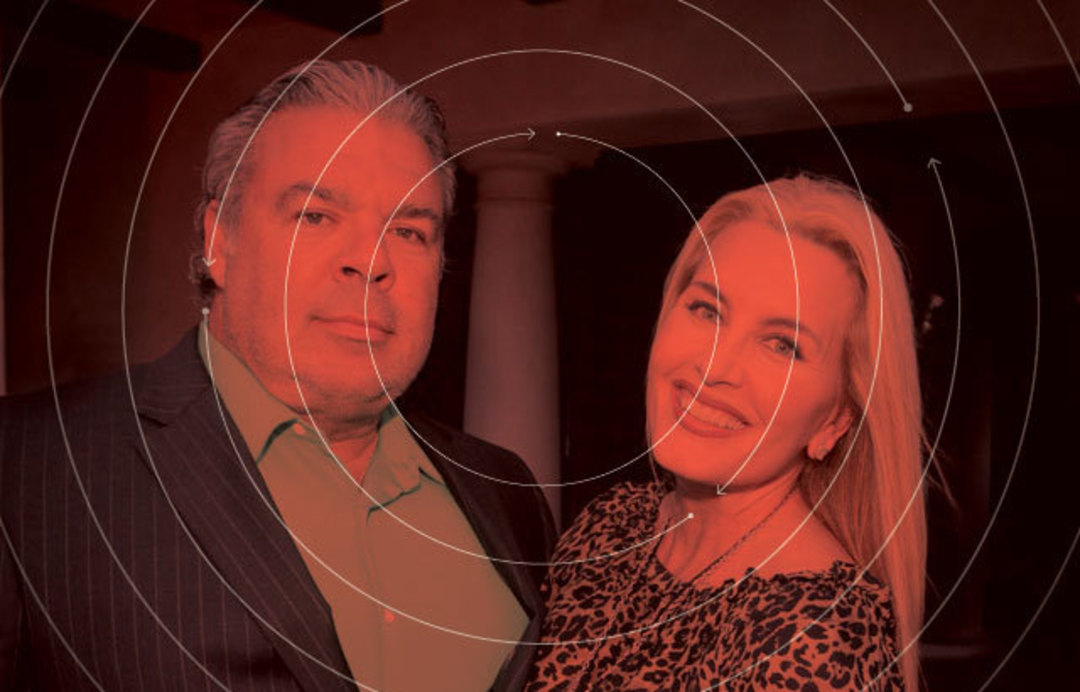

Who Are Frank and Kimberly DeLape?

Frank & Kimberly DeLape

Image: Gary Fountain

The world is full of magic things, patiently waiting for our senses to grow sharper. –Yeats

Each year, on Christmas Eve, he arrives in a bright red suit with a bulging sack of toys over his shoulder, a burly figure as welcome as it is familiar. His eyes may not twinkle nor his dimples be merry, but the Ho! Ho! Ho! is as convincing as it gets.

Soon he is at the center of the room and the children have begun to squeal and swarm, wrapping tiny arms around the man’s bowlful-of-jelly belly as he seats himself beside the Christmas tree. Then, the jolly old elf goes straight to his work, spending the next few hours handing out dozens of presents, two for every child.

To the children’s mothers, their faces both weary and grateful, as well as the staff at The Bridge Over Troubled Waters—which provides housing for women fleeing domestic abuse—he is known only as Frank. To the hundreds of kids he’s greeted over the years and for whom he is often the only father figure on this holiday, he is certainly, unquestionably St. Nick.

“They actually think they’re seeing Santa,” says Thecia Jenkins, the Pasadena facility’s education director. “The kids and women need positive male role models, and he is a reminder that there are good and trustworthy men out there who can restore their hope.”

To the rest of Houston, he is known as a prominent businessman, financier, and philanthropist, as Frank DeLape, a hulking New Jersey transplant whose husky voice and cool demeanor draw comparisons to Tony Soprano, although those close to him say he is more friendly than frightening.

Trailing close behind him at Christmastime each year, her arms full of presents and her mouth locked in the gleaming, trademark smile that has graced the city’s society pages for years, is his wife Kimberly, an Alabama native and onetime single mom who has called Houston home for more than a decade. A statuesque blonde just under six feet, she is the sort of woman who cannot help but command attention, even at the highest of high-profile events. But she is down-home enough to be approachable in the same setting, according to friends, which is to say that Kimberly DeLape has an uncommon knack for putting people at ease regardless of where she is and whom she’s talking to.

Together, they have become one of Houston’s most prominent power couples over the past 10-plus years, with Frank, who turned 60 this year, typically less visible, though only slightly so, and Kimberly out front and center. She is—or at least was until recently—one of Houston’s most sought-after fundraisers, a fixture of the city’s board circuit, with stints everywhere from the March of Dimes to the Houston Ballet to UNICEF. All agree that Kimberly is passionate in her desire to help others, but that’s not what truly sets the 52-year-old apart. What sets her apart, they say, is her uncanny ability to raise large amounts of money from the people who matter most.

“There’s an art to it,” says lobbyist and attorney Roland Garcia, a friend of Kimberly’s and a former campaign advisor to Mayor Annise Parker. “And she’s one of the few people with the right balance of skills—personality, passion, and the ability to convince others that something matters—to do it really well. She’s part of the top tier.”

Debbie Moseley, the executive director of Bridge Over Troubled Waters, agrees, noting that during the decade in which the DeLapes have been involved with the organization, Kimberly has hosted luncheons, put on a fashion show at the shelter, even paid for female residents to get makeovers. She has singlehandedly raised $500,000 for the nonprofit, Moseley estimates, an astounding sum. And husband Frank does far more than throw on a Santa Claus costume and pass out gifts every year. Moseley tells stories of a 13-year-old for whom Frank bought an Xbox, of a high school senior who needed a laptop. Frank not only bought the computer, he footed the bill for tuition at a junior college for the boy, who “went on to finish his two-year degree,” says Moseley. “It was just amazing.”

She says it has been months since she’s heard from either Kimberly or Frank, and admits she’s aware that something might be amiss—that the couple has hit a rough patch, or is perhaps in some legal trouble. Yes, she’s heard whispers of malfeasance, or was it bankruptcy? But it doesn’t matter, she says. Those are just rumors, the same rumors you always hear about people like the DeLapes, rumors that are as much a part of being rich and successful in America as mansions and fancy cars.

“I know who they are,” she says adamantly. “I know their heart.”

Others have a different opinion of the DeLapes’ heart, one you’re more likely to hear in the locker room at The Houstonian or over lunch at La Griglia than in a Pasadena shelter. Eavesdrop on the conversations of our city’s rich and socially-minded, and it won’t be long before talk turns to the couple. Their motivations and exploits, their business ventures and charity work, their websites and Instagram postings—all are endlessly scrutinized these days. As befits a world fiercely protective of its own—and utterly ignorant of its complicity—high society whispers rather than shouts the names of Frank and Kimberly DeLape. Still, the rare and unmistakable sound of moneyed griping can indeed be heard, not least because several of the couple’s wealthy friends, along with wealthy individuals elsewhere, have gone so far as to allege in court that Frank DeLape has swindled them out of sums of money. Large sums of money.

Deep in the hills of southern Virginia, along winding back roads populated by stray dogs and one-room Pentecostal churches, you will not see signs pointing the way to Mine No. 7. To get there, they say, just keep driving. You’ll know you’re close when the GPS on your iPhone stops working and the only thing the radio picks up is the voice of Kenny Mitchell. He is the pastor at Healing Hands Ministry in Squire, West Virginia, just a few hills away. Perhaps he will be singing, as he is now, delivering a fair rendition of the Southern gospel classic “Old Country Church” that crackles in and out with each bend in the road.

Just a little further down the highway you’ll find the tiny town of Jewell Ridge, Virginia, its civic boundaries delineated by a single hand-painted, black-and-white sign thrust into an earthy embankment at the top of a mountain shrouded in early-morning fog. If you’re looking for a miner, you’ll likely find one at the only commercial building in town, a ramshackle country store guarded by an American flag and a collarless, aging mutt, head drooped and fur matted.

Shortly thereafter, you’ll follow one of the miners—friendly, middle-aged—as his Nissan truck descends the backside of a mountain, and past yet more stray dogs and Pentecostal churches buried deep in the woods. Finally, on a dirt road several roads beyond the main one, you’ll see it.

Mine No. 7

Image: Peter Holley

Big rigs come and go and a hazard sign halts further progress, but Mine No. 7 is still visible in the distance. From behind a wall of trees, a roaring sound emanates from a gaping hole in the earth’s crust, one lapped by a soaring conveyor belt and surrounded by several windowless industrial buildings. Soon, your car will be thickly splattered by a heavy black mud, just like everything else on this melancholy mountain, the miners included. You’ll see the men emerge from untold depths, their clothing caked in mud, their eyes the essence of quiet resignation. It will look like a scene from the early Industrial Age—about as far from Houston’s glitzy, upper-crust social stratum as you can get.

But it was here, not Palo Alto or Wall Street or even the Energy Corridor, that Frank DeLape claimed a fortune was waiting to be made, according to a lawsuit later filed by Houstonians Lance and Alicia Smith, who had been friends of the DeLapes. Frank, the suit maintains, told the Smiths he had a controlling interest in Mine No. 7, which contained huge deposits of Virginia coal that would soon bring big profits to DeLape, just as it would to any investors who jumped aboard.

And so, on March 28, 2012, the suit alleges, “at the urging of DeLape and his wife Kimberly DeLape,” L&A Smith Investments loaned $150,000 to Benchmark Equity Group, DeLape’s company, in return for a promissory note as well as a sale of a royalty interest in the mine. DeLape, again according to the lawsuit, agreed to pay the promissory note in full with interest no later than August 31 of that year. As for the royalties, they would be doled out over 19 months and would be handsome: $730,000. According to the Smiths’ suit, DeLape told them that a personal guarantee of repayment was not necessary, as Benchmark was flush with funds, and they didn’t ask for one as the two couples were good friends, and had been for years. DeLape did present a prospectus and a sales brochure for the coal mine, which according to the suit was all a ruse, as were “bank guarantees of funds which DeLape said showed over $100,000,000 going into the coal mine project.”

Not only did Benchmark never make any payments on the promissory note or the royalty agreement, the suit maintains, but the DeLapes never intended to pay back the Smiths in the first place. The money, they allege, was instead “embezzled out of Benchmark by [Frank] DeLape and used to pay for the DeLapes’ lavish lifestyle rather than coal mining.” The DeLapes would not speak with Houstonia about court proceedings, citing a gag order, but their attorney denied all allegations of fraudulent behavior and argued that none of the allegations have yet been finally resolved by a judge or jury.

The claim seems to have gained some credence in March of 2013, however, when Frank DeLape filed for bankruptcy and didn’t list the mine among his assets. Lance and Alicia Smith, currently involved in settlement negotiations with DeLape and citing a gag order that forbids them from speaking about the case, declined comment on the suit through their attorney. Still, in an audio recording obtained by Houstonia from a bankruptcy creditors meeting in October of that year—particularly in an exchange between DeLape and a lawyer for the creditors—the extent of DeLape’s involvement in Virginia’s coal mines seems clear, or as clear as things get in this case.

Lawyer: Do you own any interest in any coal mines?

DeLape: No.

Lawyer: You do not?

DeLape: Individually?

Lawyer: Individually you do not. Does the company you own 100 percent, Benchmark, do they own any interest in coal mines?

DeLape: Not sure.

Lawyer: You don’t know if your company owns any interest in coal mines?

DeLape: That’s what I just said.

Testimony continued for a few more minutes, at which point the lawyer asked, “In the last two years, have you ever owned an interest in any coal mine?”

“No,” DeLape is heard to reply.

If the dispute between the Smiths and DeLape were an isolated incident, it might be easily dismissed as a failed business deal, or perhaps just a falling-out between two wealthy couples. But an examination of DeLape’s bankruptcy court records tells another story, two of them actually, and the allegations are of a piece with the Smiths’ case.

According to the first suit, DeLape, through an intermediary, approached a group of Minneapolis investors known as the After Midnight Group in 2011 claiming that he had “acquired all of the rights to 23 million tons of coal located at the Fiatt Coal Field in Cuba, Illinois.” DeLape promised AMG, again according to the suit, that he would obtain a $25,000,000 loan to process and transport the coal, and in June of that year invited several members of AMG to meet with him in the Clear Lake offices of Blackstone Worldwide Partners, another company owned by DeLape. The suit describes what happened next as “a tremendous dog and pony show” designed to convince the men of the investment’s value, one in which “Kimberly DeLape, the CFO of Blackstone, served food and drinks. There were photos, PowerPoint presentations, a video, and documents.”

Frank DeLape claimed that he owned all of Fiatt’s coal, according to the suit, had the machinery ready to load it for transportation, and that all he needed from AMG was $1 million, which would be used to build a road into the site. The men returned to Minneapolis with the recommendation that AMG invest in the deal, which it did, giving DeLape the $1 million asked for.

Over the next few months DeLape continued to promote further investment opportunities, according to the AMG suit, even going so far as to fly to Minneapolis with “a tube full of dirt” from a prospective mine in Utah that DeLape claimed he was having tested in a laboratory for its gold content. AMG declined to invest a second time. February 2012, the deadline for repayment of their first investment, came and went, and despite DeLape’s assurances to the contrary, “AMG was never paid anything,” according to the lawsuit.

Just a few months later, in April, DeLape approached Manny Bello, a New York–based businessman—“a peerless force in the evolution of angel investing,” according to his website—on behalf of Benchmark Equity Group, a Delaware corporation headquartered in Texas and owned by DeLape. According to Bello’s suit, what DeLape sought from him was a loan in connection with “an exciting bond trading opportunity,” meanwhile producing account statements and other supporting documentation designed to convince Bello that he had already invested millions of dollars of his own money, and that the New Yorker’s contribution “was the ‘final piece’ needed.” That final piece was $765,000, according to Bello, whose suit says DeLape promised to pay the money back with interest 90 days later.

“Bello accepted DeLape’s personal guarantee,” it reads, “because DeLape told Bello that he had millions in assets, including a home in Houston worth millions and real estate worth $52 million in Panama.”

DeLape took Bello’s money, used it not for investments but “to personally enrich himself,” and never paid it back, according to the suit. Instead, less than a year after meeting Manny Bello, DeLape filed for bankruptcy.

On a Thursday evening this past May, The League of Professional Women, a group within the women’s ministry at Lakewood Church, met in a chapel on the large church’s third floor. Offering a stage, a piano, and enough seating for 600 people, the chapel, with its plush, navy blue carpeting, is a popular location for weddings at Lakewood. But on this night the members of the ministry were gathered to hear a guest speaker: Kimberly DeLape. Her talk, entitled “Reinvent YOU,” challenged listeners to consider their “vision and purpose.”

“Who you are is synonymous with what you bring to the table…your personal brand,” read a description of the event on the ministry calendar. “Make yourself more marketable in the workplace as Kimberly DeLape, CEO of Brand Moguls, leads an inspiring panel on discovering your personal brand, choosing the right opportunities, and a fresh perspective to shift into YOUR BEST YOU!”

As a prominent and active member of Lakewood Church, and a successful businesswoman, DeLape would seem an obvious choice to give a talk to the league. A friend of Victoria Osteen—wife of Lakewood pastor Joel Osteen—Kimberly, along with her husband Frank, are often seen in the church’s VIP section, a cluster of seats near the stage often reserved for family, friends, and important guests.

Brand Moguls, meanwhile, a company Kimberly founded in 2008, specializes in helping companies retool their identities through website design, video production, and marketing. The firm has worked with a variety of friends and business associates of the DeLapes, although its greatest success story, at least in terms of accolades received, was its campaign for Emerald Monkey Eco-Luxe Resort, an exclusive island getaway then in the planning stages, with private villas scattered on the hillsides of Isla Pastor, part of the Bocas del Toro archipelago off the Caribbean coast of Panama.

The resort’s developers? Kimberly and Frank DeLape, who intended to build what they called the world’s first five-star, zero-carbon-footprint community, a development that would rely on hydroelectric and solar power yet still possess luxurious amenities like a fitness center, gourmet restaurant, and Balinese-inspired villas with private plunge pools. According to CultureMap, a news and entertainment website, the resort had already won awards for its design in 2009, “even though,” read the article, “the project won’t be completed until late next year.”

The resort was not completed the following year, or ever, it seems, and the only question is whether it ever actually broke ground. An online search reveals a variety of ads for Emerald Monkey, as well as a number of computer-generated photos from Brand Moguls, but no customer reviews or other evidence that the resort has hosted guests. Attempts to book a room, even months in advance, were unsuccessful. There’s a good reason for that, according to Okke Ornstein, a journalist based in Panama who says he met DeLape several times in that country: the resort doesn’t exist.

DeLape was behind the “failed ‘Emerald Monkey’ project on Isla Pastor and a whole bunch of other projects that never materialized,” according to an email Ornstein wrote to Houstonia, adding that DeLape was “a big talker.… He and his people were all over the map with their projects.”

The DeLape Residence in Seabrook

Image: Max Burkhalter

The DeLapes originally met at Houston’s Neiman Marcus in the Galleria, according to friends, where Kimberly worked (“as a perfume girl,” as one put it), and married in 1999. Their home, then and now, is on a peninsula in El Lago, which, as it happens, was once a favorite hiding place for Jean Lafitte, the notorious French pirate. A 13,000-square-foot estate with 8 bedrooms, 12 bathrooms, and a 6-car garage, the DeLapes’ faux-Italian villa sits majestically on Lake Taylor not far from NASA, its pool set off by bubbling fountains, its grounds dotted with statuary.

The home’s occupants are eye-popping presences too, especially within the rarefied climes of Houston society. “Over the last 14 years,” according to a children’s book by Kimberly published earlier this year, “Kimberly has helped raise millions of dollars for organizations by co-chairing events, serving on various committees and serving on numerous charitable boards in the community.”

The couple’s names began appearing in the Chronicle’s society pages at least as early as 2005. (Full disclosure: the author worked as a reporter at the Chronicle until 2012, but never wrote for the society pages or covered the DeLapes). The same year, the Chronicle published a story about the fall of Isolagen, a biotech company with Houston ties, a story that, somewhat surprisingly, never mentioned Frank DeLape, even though he had been chairman of the company’s board.

The Isolagen process—in which a patient’s own cells would be harvested from a biopsy, grown in culture, and then transplanted back into the patient—was sometimes referred to as the grow-your-own-facelift technique, a promising anti-aging treatment whose cosmetic effects would hopefully aid burn victims too. But after “scientists reported disappointing results in late-stage trials,” as the Chronicle put it, Isolagen’s stock took a nosedive, at which point a class-action lawsuit was filed “alleging that company officials misled them with false information.” In the suit, which the Chronicle did not subsequently report on, Isolagen shareholders claimed that although company executives had become aware that their treatment would not likely gain FDA approval, they continued to raise capital anyway, even as the executives themselves were cashing in their own stock. DeLape alone sold $5 million worth, according to the suit, which Isolagen contested but then settled in 2008, just before filing for bankruptcy.

Over the next several years, even as more of their business dealings began raising questions, even as they turned their attention to coal miles in Appalachia and the beaches of Panama, no story about the DeLapes ever appeared within the Chronicle’s news pages. Only the society pages seemed interested in the couple, and their conspicuous presence there played no small part in the DeLapes’ rise within the Houston social scene.

It was Hurricane Rita in 2005 that first brought them to the paper’s attention. Then-Chronicle society columnist Shelby Hodge, calling the storm “a great equalizer,” informed readers that “Kimberly and Frank DeLape, from Clear Lake” had been forced to evacuate, taking shelter in Carolyn Farb’s River Oaks mansion, where the trio’s storm preparations had included buying plywood from a hardware store and provisions from nearby Central Market. But it was the DeLapes’ attendance at Houston Ballet’s 2007 Butterfly Ball in the Wortham Center, amid “an ethereal décor befitting the romantic nature of dance,” that earned the couple their first real mention in the Chronicle. And by 2010, Kimberly DeLape had become a “social butterfly” herself, impressing reporter Lindsey Love at a UNICEF gala held at the home of socialite Becca Cason Thrash. DeLape’s metamorphosis continued to fascinate the Chronicle in the years ahead, so much so that by 2012, the paper was even publishing her New Year’s resolutions, of which there were seven (“because that number represents completion in all things spiritual,” she told them).

But nothing on the DeLapes’ social calendar was more warmly received by the press than those Christmas Eves in Pasadena, and not only at the Chronicle. Other media outlets found themselves irresistibly drawn to the heart-tugging scenes that played out there, among them CultureMap, to which Shelby Hodge decamped in 2009. “Who knew,” she wrote on the website in 2009, “that the imposing, larger-than-life Frank DeLape would be such a congenial and believable Santa Claus? Or that he has such a generous heart?”

Over time, thanks in part to Frank’s legal battle with locals like Lance and Alicia Smith, word of the DeLapes’ troubles and bankruptcy seems to have spread to every tony enclave, private club, and newsroom in the city. As such, the couple appears to have become persona non grata. Still, few will publicly broach the subject of the DeLapes’ alleged misdeeds. Two of the couple’s alleged victims, Lance and Alicia Smith, were still under a gag order at press time. Members of the local press, meanwhile, including those who have covered the DeLapes’ adventures in society, are silent too. Although an email written by Shelby Hodge and obtained by Houstonia confirms that she knows couples who are “furious” about their treatment by the DeLape, her only public response thus far has been to stop mentioning the couple in her CultureMap columns.

And charities and other organizations that have worked closely with the DeLapes are also silent. Susannah Masur, a spokesperson for UNICEF, would only confirm that Kimberly DeLape joined the organization’s board in 2006 and that her term expired this year. Asked whether UNICEF is aware of the bankruptcy proceedings and accusations of fraud leveled against their former board member, and whether they played a role in DeLape’s exit from the board, Masur declined to comment directly.

“Yes, the leadership of the US Fund for UNICEF is aware,” she said. “As a matter of policy, we do not comment on ongoing litigation.” Houstonia also reached out to the Houston Ballet (whose annual ball was co-chaired by Kimberly DeLape and Lance and Alicia Smith in 2009, all of whom were board members), and the local chapter of the March of Dimes, where Kimberly served on the board until 2013. Both acknowledged DeLape’s involvement, but neither would comment on whether they had parted on good terms with her.

In an atmosphere such as this, in which charities, fellow board members, and the press are unable or unwilling to speak publicly to the allegations against the DeLapes, the full extent of the couple’s guilt or innocence may never be known.

The list of potential victims, from charities to investors, is a long one, and it reaches far beyond the Houston area. Some claim to know the DeLapes’ “heart,” as Debbie Moseley put it, although for others, the question of whether they were conned is an ongoing question.

Retired Col. Eugene W. Reaves is one of these. By the fall of 2007, the veteran says, he had grown tired of his expat adventure in Panama, where he lived for five years following his 33 years in the Army. And so he had no problem trading the land rights to a property he owned, a picturesque Panamanian island called Isla Pastor, for a $1.2 million promissory note. DeLape gave him the note, Reaves says, with the intention of building an eco-resort on the island, saying he would repay Reaves quickly and in full, offering a quick return on his investment. Reaves believed him.

“When my wife and I met Frank, I told him the worst thing about Panama is that you can’t get a good pecan pie,” Reaves recalls. “That Christmas, and the three after that, there was a pecan pie from Frank waiting for me wherever I was.”

Photo courtesy of Instagram

The men enjoyed an easy friendship based, in part, on their mutual history in the military (DeLape attended the Naval Academy but did not graduate). In addition to being a knowledgeable businessman with impressive financial backing, Frank, whom Reaves refers to as a “big teddy bear,” had a way of looking out for his new friend when it mattered most. After Reaves returned to the US, he recalls, DeLape found a new home for an adopted stray dog that Reaves hadn’t been able to bring back with him. “I’m not sure he was a big dog lover, but he knew it was important to me,” Reaves says.

DeLape had already begun to sour on Panama by 2009, Reaves believes. He remembers the moneyed businessman telling him that there was too much corruption in the country, and that a plan to build underwater power lines had proved too ambitious and expensive. DeLape was bleeding cash, believes Reaves, although he vowed he would still find a way to pay the trusting veteran back as soon as he could. Reaves, figuring his buddy had been ensnared by corrupt Panamanian politicians, felt sorry for DeLape.

Curiously, that same year, the DeLapes were busy promoting their plans for Emerald Monkey in the Houston media. That’s when CultureMap wrote about the still-in-progress resort. “The DeLapes couldn’t be happier,” said the article, referring to the awards Emerald Monkey had received.

Today, Isla Pastor, the speck of volcanic, Caribbean rock on which the DeLapes planned to build Emerald Monkey, is almost entirely deserted, according to its former owner. Google Maps satellite imagery, updated this year, shows a few indiscernible structures peaking out from a dense jungle canopy, but no infrastructure, no clearings, and no resort.

What of Frank DeLape’s relationship with Col. Reaves? “We talked for the next four years, and he initiated those phone calls, and he’d say, ‘Oh I’ve got this thing going, and I’m going to be able to pay you in a few weeks,’” Reaves recalls. “He never did, but at least he’d say that.”

Now 63 and unable to live on his fixed income, Reaves admits that although DeLape paid a sizable chunk of what was owed him for the island up front, he could really use the rest of the money—around $300,000. In fact, he desperately needs it, he says. Presently living in a small Missouri town and unemployed, he wonders whether anyone will hire a graying senior citizen like him. Is he angry at DeLape? Yes, but he’s even angrier with himself. He can’t stop asking himself why he allowed Frank to give him a promissory note instead of a check.

“I screwed up, I really did,” he says.

There was a time, early in DeLape’s bankruptcy hearings, when attorneys forbade the men from talking. More recently, however, the phone calls from DeLape have begun once again, Reaves says, although he still hasn’t received any money. He isn’t one to trust many people, but for some reason, one he can’t fully explain, he trusted DeLape, and still does, he says. The alternative, he admits, is frightening.

“I still believe he would pay me if he could,” he says. “If he’s a con man, well, he’s the greatest con man on earth.”

Even as the gala invitations come less and less often, and allegations continue to mount, the DeLapes seem to be taking things in stride. Still, there are moments when the façade cracks and hints of desperation can be seen. What expression did Kimberly DeLape wear, one wonders, when she began visiting Houston-area pawn shops last year? Was the CEO, fundraiser, and philanthropist flustered? Uneasy? Did she wear glasses? A hat? Was she nervous that someone might recognize her tall frame and blonde hair from the society photos, or the many appearances as a fashion expert on Deborah Duncan’s Great Day Houston? The answers to these questions, of course, are unknown.

What is known is that Kimberly DeLape made visits to multiple pawn shops during a four-month period beginning in July of 2013. On July 3, she received $12,650 for a small treasure trove of jewelry that included 14-carat emerald earrings, a tennis bracelet chain with rubies, diamond hoop earrings, a heart necklace, and more. Two weeks later, she received $3,000 for seven Prada, Fendi, and Valentino handbags, and six days after that was paid $1,000 for four additional handbags. (If DeLape has a shopping weakness, it is for handbags, records reveal. Her collection included leather, suede, python, zebra, animal print, and studs, and she appears to have had a special affinity for green snake skin.)

By the time Kimberly DeLape stopped going to pawn shops, in late October, she had pulled in close to $70,000, according to bankruptcy court records for the Southern District of Texas.

Around the same time, Frank DeLape—who also made at least one trip to a Richmond Ave. pawn shop in September, where he received $1,913 for some sterling silverware—was wading through local bankruptcy court, where a judge had already appointed a trustee to appraise the entirety of the couple’s worldly belongings.

At a creditors meeting in March of this year, DeLape’s lawyer, Reese Baker, estimated his client’s total debt at $2.2 million. Meanwhile, DeLape stated in court that his personal bank accounts had all been shut down, and that his home, which was going on the market (and remains so—asking price: $5,495,500) was his sole principal asset. His companies—Blackstone, Benchmark, and others—were now of zero value, DeLape stated.

“They’re set up for really just transactions. I mean, they’re a pass-through,” he told the court. “They don’t really have employees or they don’t have any properties or desks or any of that stuff.”

At the same meeting, Ross Spence, attorney for the Smiths and AMG, asked DeLape about some pending business deals he had mentioned at a bankruptcy hearing several months prior, deals that were supposed to help DeLape repay the creditors to whom he owes money. Why, Spence asked, would DeLape not state for the record, under oath, the names of any of the other parties involved in his present deals?

“Because,” DeLape responded, “people in the room will put it all over the society world, and I’m not willing to put that business at risk, because it’s how I’m going to pay these creditors back.”

DeLape told the court he had five such deals in the works. “Yes, new deals coming now all the time,” he said. “Just got a deal I feel pretty good about…two of them…in the last five to seven days.”

The status of such deals, assuming they actually exist, is unknown. Ross Spence says that a settlement between his clients and Frank DeLape has been reached, but has yet to be approved by the court, which could take months. As for the DeLapes themselves, it’s difficult to imagine what could be going through their minds right now. But that too will likely remain a mystery. Here, as elsewhere, all we know about the DeLapes is what they want us to know.

“Me and Big Daddy just chillin at Sunset at Farfalle Sul Lago!” So reads the caption to a photo Kimberly posted to her Instagram account in June. In it, Frank is seen at sunset, relaxing in the pool with the bubbly fountains, a cigar in his hand. All that can be seen of Kimberly is her toes, at the bottom of the picture, the pedicure apparently recent, the toenails blue. The photo has so far received 27 likes.

During the course of this investigation, Houstonia reached out multiple times to the DeLapes, speaking to Frank once briefly (he declined to talk on the record), and a few times to Kimberly. During one call to the latter, we asked about two Brand Moguls employees pictured on the company’s website, saying that we had been unable to verify the men’s identities, locate their home addresses, or find social media accounts for them. Furthermore—as we also told DeLape—we had contacted a former Brand Moguls intern who claimed to have never heard either man’s name.

Would Kimberly DeLape provide us with contact information for the employees or anything else that might help us establish their existence, we wondered? After a long pause, she refused.

“They’re real,” she snarled, then abruptly ended our conversation.

Later the same day, we placed a call to the Brand Moguls office. In previous instances such calls had gone unanswered or the phone rang indefinitely. This time, after a couple of rings, the call was answered. A recorded message began to play.

“Hi, you have reached me on the greatest day of my life!” said a voice, a voice that almost certainly was Kimberly DeLape’s, a voice whose chirping effervescence might have been mistaken for sarcasm if it belonged to anyone else.

“Please leave your name, number, and a brief message,” it went on, “and I will get back to you as soon as possible. And I hope you continue to have a great day—because I know I will. Bye!”