Futurama: What’s Next for Houston’s Neighborhoods?

Image: Nurit Benchetrit

Houston, 2016: We have, without a doubt, doubled down on sprawl. The new Grand Parkway, our gigantic third loop, will be 170 miles long when complete in 2023. And its construction is already ushering in wave after wave of brown-roofed homes in master-planned subdivisions and grocery-anchored strip centers in far-flung corners of the metro area—only the latest evidence that the Houston of the future will continue to look, in some ways, like the Houston of the present.

But. But. As Houstonia grows—the population of the eight-county region, currently 6.3 million, is expected to increase to 10 million by 2040—it will inevitably change. Developers have already started to focus on what the next generation of Houstonians will want, replacing dead malls with outdoor “town centers,” for example, and swapping parking lots for street-facing retail on the ground level of larger, vertical developments.

“A concentration of activities is necessary for a vibrant neighborhood,” said Bill Fulton, the director of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research at Rice University. “If you’re going to have a vibrant neighborhood with vibrant street life, what that generally means is that you need a lot of people there. The best way to do that is to have multistory buildings where people either live or work.”

Which brings us to an interesting thing happening right now—a thing for which Houston has never been known. As the inner city densifies, developers and designers and urban planners have started to consider planning for that growth. That’s right—planning. In Houston. Curious about this bizarre turn of events, we assembled a panel of experts to find out what the city’s neighborhoods of the future might look and feel like.

According to the Kinder Institute’s most recent Houston Area Survey, 49 percent of Harris County respondents said they prefer areas with a mix of developments, including homes, shops and restaurants.

Without a concentration of activities and people either living or working in an area, you’re going to get nothing but people driving in and out. That, of course, leads to traffic. In the same Kinder survey, 65 percent of respondents said traffic has gotten worse over the past three years. Asked what they consider the greatest problem facing Houston today, respondents’ No. 1 answer was traffic.

But how do you turn a city of drivers into a place with a thriving public transportation system? “There are two worlds, probably in any city but certainly in Houston,” David Crossley, president of urban think tank Houston Tomorrow, told the diverse crew that stopped by the Houstonia house recently for wine, cheese and a lively discussion. “One world is the world where you’re required to have a car to do everything. And the other one is where there’s a possibility of walking to the store, of having access to some kind of transit.”

In Crossley’s vision of the future, Houston’s multiple economic hubs—including downtown, Uptown, the Energy Corridor and Westchase—will be linked together, allowing Houstonians to live and work in various areas without needing to drive. “We’ll have many walkable neighborhoods, with plentiful goods and services, that are connected by high-quality transit service to other walkable urban neighborhoods.”

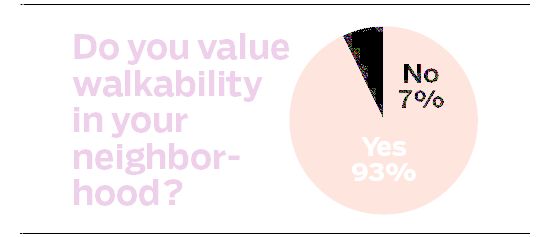

But while “walkable urbanism” has become a big buzzword in planning and development, Houston, which is larger than New Jersey, has never been a land of pedestrians. Yes, half of Houstonians want to live in a walkable area, but the fact remains that the other half are happy to keep their cars and big yards, thank you.

Of the metro area’s 6.3 million people, 2.2 million live in the city limits, with only half a million of those residing inside the Loop. As a result, ringing Houston in all directions, “there are cities that have been created—Sugar Land, Katy, Woodlands, League City, Clear Lake,” said Paul Layne, a vice president of Howard Hughes Corp. in charge of The Woodlands Development Company. “And those cities have great schools and a great quality of life if you want to be there.”

Layne stressed that people’s preferences vary wildly, and “there’s something for everyone in Houston.” But how big a difference is there, really, between what the car-free residents of Midtown and the mansion owners of The Woodlands want?Of the metro area’s 6.3 million people, 2.2 million live in the city limits, with only half a million of those residing inside the Loop. As a result, ringing Houston in all directions, “there are cities that have been created—Sugar Land, Katy, Woodlands, League City, Clear Lake,” said Paul Layne, a vice president of Howard Hughes Corp. in charge of The Woodlands Development Company. “And those cities have great schools and a great quality of life if you want to be there.”

Peter Merwin, an architect at Gensler who heads up its Houston mixed-use practice, said he thinks the two groups actually share plenty in common. “We’re talking about suburban development or ring development around Houston, and we’re talking about urban infill development,” he said. “But the model that we’re talking about is sort of similar in both conditions, right?”

Whether it’s open-air town centers where residents can shop, catch a movie, get a bite to eat or relax in the park without getting back in their car, or a fully walkable neighborhood where your grocery store, dry cleaner and favorite bar are across the street, both Inner Loop and Outer Loop residents are flocking to more connected spaces.

According to the Kinder Institute, more than 60 percent of Inner Loopers prefer walkable urbanism, but a full 40 percent of those in Fort Bend and Montgomery counties do, too. “We’re talking about vibrant, walkable places where people can live and go out and eat,” said Merwin. “We’re talking about similar aspirational goals for the resident in both of those things.”

As the evening went on and plastic wine glasses emptied, the experts kept coming back to another theme: affordability. Whether we were talking about luxury Inner Loop condos or well-located suburban homes, one thing was indisputable: Both come with a hefty price tag.

“A lot of people are chasing that upscale market, but there’s this huge demand for folks in the middle or with lower, more moderate incomes,” said Ann Taylor, vice president at Midway Companies, whose developments include CityCentre, a landmark mixed-use development for Houston that replaced the mostly-dead Town & Country Mall. “There’s a huge demand for what they’re calling ‘the missing middle.’ I think that’s a challenge for Houston.”

In 2011, the Center for Houston’s Future, a think tank affiliated with the Greater Houston Partnership, came up with two different scenarios for what Houston might look like in 2040. In the first, the city struggles to grow before finally focusing on improving the quality of life for all classes of Houstonians, from social programs to education. In the second, business is booming, the city’s growing rapidly, and the chasm between rich and poor is getting wider. Catherine Mosbacher, the think tank’s president, said the second scenario has already begun to unfold.

“Houston is the most income-segregated major metro area in the United States,” she said. “So I hope the discussion isn’t just all about gentrification, and ‘let’s just have the good life for people who can afford it.’”