What Happens When You Change a Street Name?

Dowling Street is no more.

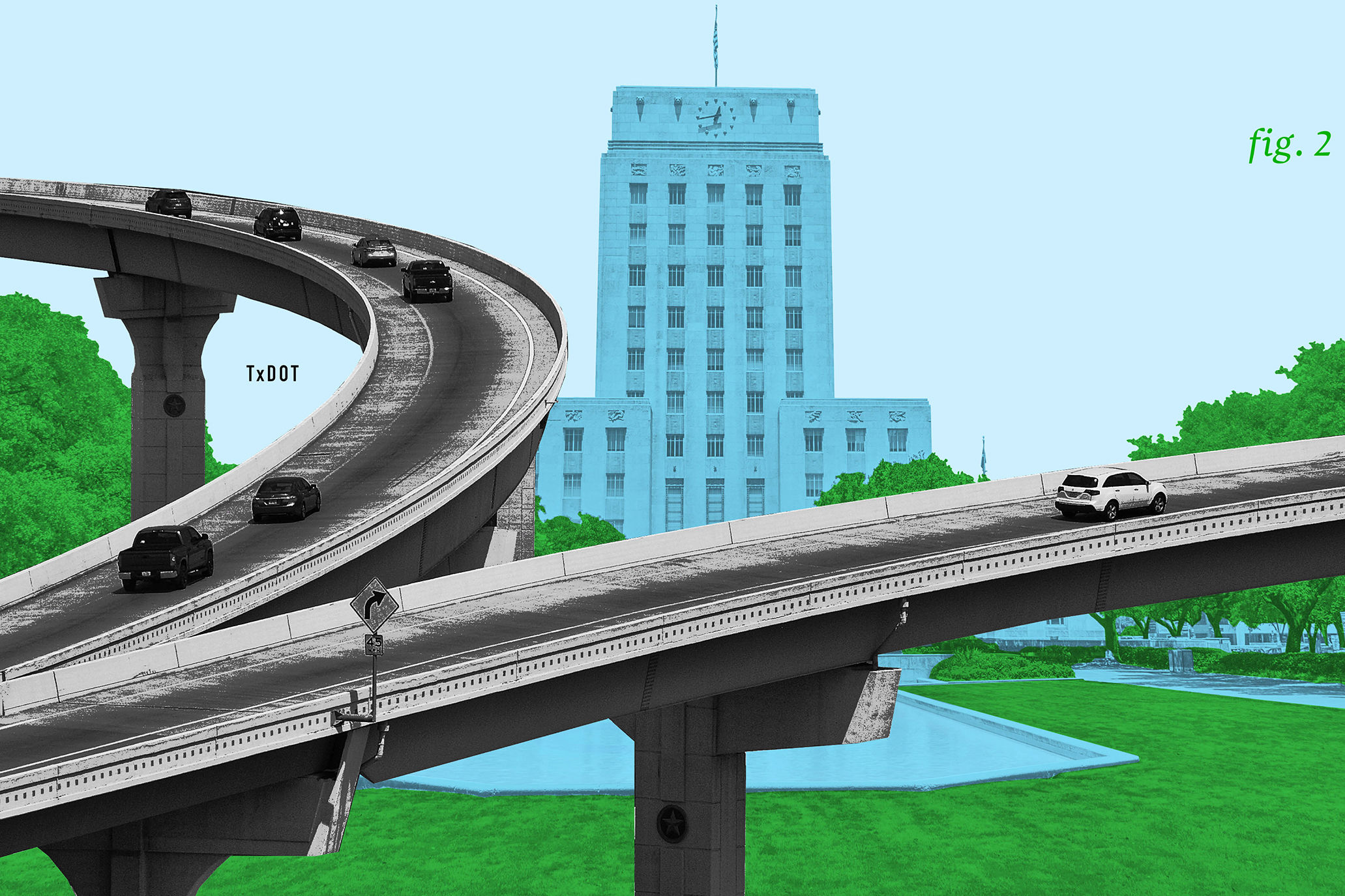

Image: COURTESY BLUETILEPROJECT.COM

On a hazy day in early June, Not Jus’ Donuts relocated from Dowling Street to Emancipation Avenue in about 10 minutes. City workers arrived outside the Third Ward bake shop in a hydraulic lift, climbed above the adjacent intersection, and swapped out one street sign for the other.

That moment caught manager Andrea Jackson, whose mom owns the shop, by surprise—in a good way. “It should have been renamed years ago,” she says.

The sign swap was the culmination of more than a year of community activism to remove the name of Richard Dowling, a Confederate war hero, from the thoroughfare in the historically black Third Ward. State Rep. Garnet Coleman started a petition for the name change in 2015 that led to a protracted process of hearings and procedural maneuvering.

In January, with City Council set to vote on the matter, Mayor Sylvester Turner rebuked Dowling apologists, and the change was approved unanimously, with the goal of transitioning by Juneteenth (June 19), the day marking the end of slavery in Texas and, this year, the rededication of Third Ward’s Emancipation Park.

But mixed in with the history is a set of pedestrian questions left unanswered: What’s in a street-name change? Where do the old signs go? What does the city take care of, and what are property owners left to handle themselves?

As far as the street signs, the city replaced approximately 80 of them at an estimated total cost of $30,400—almost $400 a pop—donated by former at-large councilmember Peter Brown. Houston Public Information Officer Alanna Reed says the old Dowling Street signs remain “in a secure facility,” supervised by the Department of Public Works and Engineering, until Mayor Turner decides “how to handle the demands for them.” The city also took care of the absolute essentials, rerouting 911 calls to the proper address and forwarding mail.

Maps are a bit trickier, as all the city can do is push out the information and wait for third parties to download it. Google updated its map almost immediately, but the ghost of Dowling continues to linger on Yahoo and MapQuest.

Jackson says Not Jus’ Donuts had to personally update various business listings online to make customers aware of the change. But she’s unable to fix several thousand previously printed direct mailers that are now outdated. A new round will cost more than a thousand dollars, although Jackson recognizes it is a one-time expense. “Once they change it, it’s permanent,” she says about the name.

File-It, a bookkeeping service located a few doors down from the doughnut shop on Emancipation Avenue, finds the change has caused some minor confusion among clients. “The first question they ask is, ‘Oh you moved your office?’” says Neferteri Williams, who works at the front desk.

But one of those clients, Edwin Harrison, general manager of Row House Community Development Corporation and a proponent of the name change, shrugs off these hiccups; streets have been renamed before, and the name had to go. He says the inconvenience should be considered within the larger context of ceasing to lionize Dowling, a man who fought to preserve slavery.

“I don’t think there are any black folks around here who will be disgruntled about this,” Harrison says. “If you’re doing the right thing, does it really matter what it costs?”