What Will Happen to Houston's Salvadoran Immigrants?

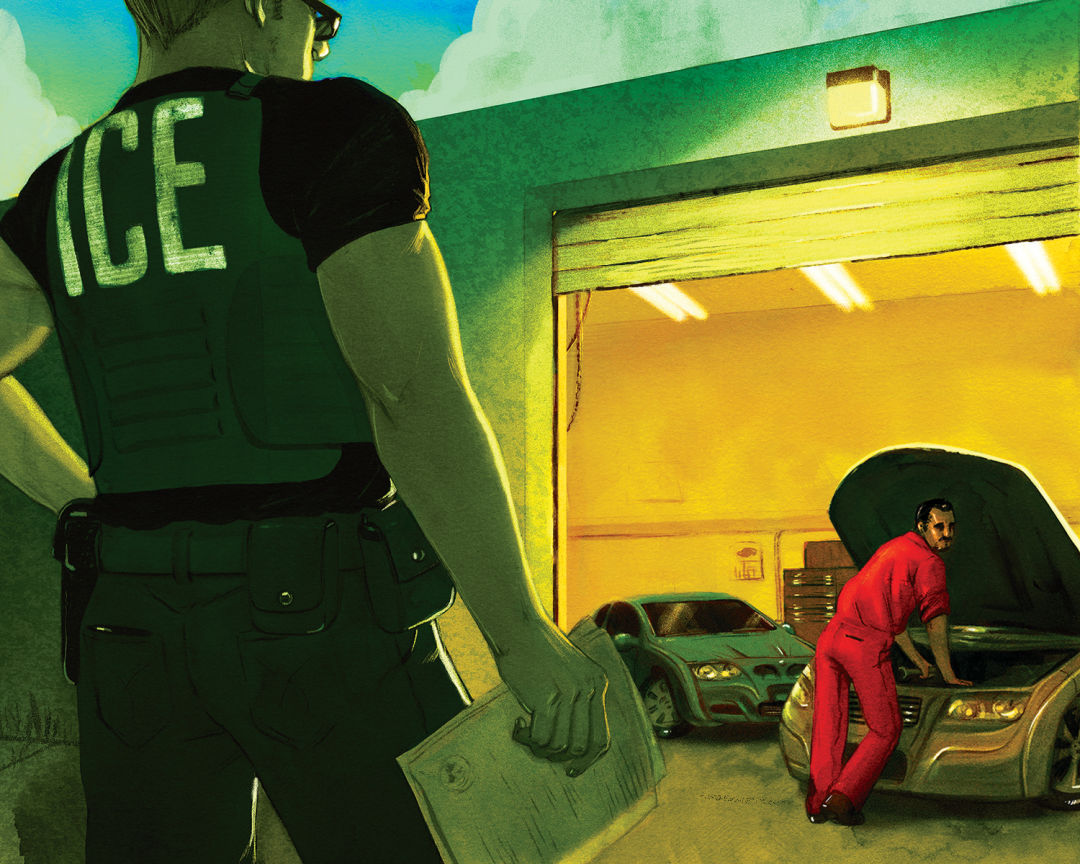

Image: Zoë van Dijk

September 9, 2019: It hangs like a dark cloud over Manuel Flores’s entire existence. This is the date that temporary protected status (TPS) for nationals of El Salvador—a designation that, for the last 16 years, has granted eligible Salvadorans the ability to live and work legally in the United States—is set to end. In January, the federal government announced it would revoke TPS for Salvadorans 18 months after the current designation expires—this month, on March 9.

Flores is a 46-year-old father of two who’s been in this country for some 25 years. He originally came to the U.S. through a different immigration program—the now-defunct ABC Settlement Agreement, which essentially granted asylum to some Salvadorans and Guatemalans—and settled in Houston.

Today, he’s lived here longer than he’s lived anywhere else, through a marriage and a divorce, the birth of his daughters, the start of his auto-repair business, hurricanes, tropical storms, droughts, recessions, and, the whole time, repeated extensions of his status through the TPS program, under both the Bush and Obama administrations.

“Just to get to the United States, for anybody, is a dream,” Flores says in Spanish as his immigration attorney, Carolina Ortuzar-Diaz, translates. “When you’re fleeing poverty and a civil war, it’s a relief. You feel like you are free.”

The TPS program is being canceled, feds say, because its original justification—El Salvador’s 2001 earthquake and the widespread devastation that followed—is in the distant past. They point to the word “temporary” right there in the name. But Flores and many of the more than 200,000 others with TPS across the U.S.—36,300 of them in Texas; 19,000 in Houston alone—long ago put down roots here. And many have nothing to go back to in their home country.

For Flores, returning is unthinkable. He actually left El Salvador at 14, first traveling to Mexico to find his estranged mother and get work. His familiarity with his home country is reduced to childhood memories and dispatches from his only remaining contacts there: a single friend and two sick, elderly aunts who depend entirely on his monthly $350 checks. Years ago, that money fulfilled a promise to the grandmother who raised him—it built her a modest home, where she lived until she died.

Flores knows El Salvador’s poverty, crime, and violence are even worse than what he fled when the nation was embroiled in a brutal civil war. Then, a young Salvadoran had two options: fight for the guerillas against the government, or fight for the government against the guerillas. Boys were pulled from school and strapped with machine guns. Flores jokes that he’s only alive because he was too skinny to support a weapon.

As a child in El Salvador, Flores learned to repair cars, something that assisted him when he arrived in Houston, where jobs were plentiful, at age 19 or 20. He found work at dealerships across the city, sending home money from his very first paycheck.

Eighty-eight percent of Salvadorans with TPS participate in the labor force, compared to just 63 percent of the total U.S. population. Six years ago, Flores became one of the 11 percent of TPS recipients who are self-employed. His body shop employs two full-time workers and a slew of sub-contractors. He himself works 10-hour days.

Over half of Salvadorans with TPS have lived in the U.S. for 20 years or more. Collectively, they have 192,700 U.S.-born children, 20,300 of whom live in Houston, including Flores’s two daughters. One is 18 and plans to attend medical school; the other was born the day before Flores spoke with Houstonia, fidgeting with the hospital bracelet still on his wrist.

“We don’t have the gift of being born here; we’re not American in that sense, but we work hard and we try to do things in the proper way,” he says. “I think we deserve to stay as long as we continue to contribute to this country, because we want this country to be number one.”

Flores wants to expand his business, open a dealership, invest in property—all ambitions currently deferred. Should he be separated from his family, he’ll surely lose his means of supporting the children and elders who depend on him. A directive to “go home” is nonsensical to him, he says. He is home.

“When I came to this country, I thought, ‘Here’s where I’m going to die,’” he says. “It still feels like I’ve fought so hard for so long for everything I have, and suddenly everything is just falling apart. … I have no reason to go back. I have planted my roots here, and I think I have been able to produce a good harvest.”