Houston Is the Card Skimmer Capital of the Nation. What Is Being Done About It?

Image: Neil Webb

It happened to me back in 2017—the moment I crossed the Harris County line, in fact. I was at the wheel of a Ryder truck, a thunderstorm looming overhead, my mother following behind in my Tacoma. We pulled into a station on I-10. Popped out. I inserted my debit card at my pump, then at hers. As we filled our tanks, the skies opened up right there.

I didn’t realize what had happened until a week later when, settled into a Montrose apartment and a new job, I went out for a pizza at Love Buzz. “It’s declined,” the bartender said. “I mean, I can try it again.” She did. “Yeah, still declined.” It was embarrassing, but only a few other customers and a statue of Marge Simpson witnessed the rejection, and I was lucky—I had another card on me.

Back home I pulled up my account and noticed a few strange charges—small purchases at Duane Reade, a taxi ride, a MetroCard, something at Nordstrom. Somebody was living it up in New York City. Suspicious charges to account, a robot, and then an actual human, informed me when I called the bank. It wasn’t quite the welcome I’d hoped for from Houston, I’ll admit.

Skimming—the theft of credit, debit, and fuel card information, typically at gas stations, for the purpose of spending someone else’s hard-earned money—is a problem nationwide, but Texas currently accounts for 35 percent of the financial losses incurred via this type of crime in the entire country, with Houston skimmers making up a large portion of that, according to experts.

“You’ve got three hot spots—Miami, Las Vegas, and Houston,” Sergeant Adam Colby of the Tyler Police Department financial crimes unit said in May, testifying before the Texas House of Representatives in favor of new legislation to fight the problem. “Houston is the biggest one.”

Three quarters of the 46 skimming arrests made in Texas last year, all felonies, were for crimes committed in Houston. While that’s revealing, HPD Sergeant Jeff Headley, who works in financial crimes and testified alongside Sgt. Colby, said there are thousands of such scammers in the Bayou City alone. “It’s a profession for them,” he told the House.

Texas Department of Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller echoed that statement when reached by Houstonia. “It’s organized crime,” he said. His agency inspects gas pumps and runs a consumer-alert system, placing “Call Sid Miller” stickers at stations and releasing informative YouTube videos. “It’s not only getting more frequent, but technology is constantly evolving,” Miller explained. “We haven’t kept up.”

Skimmers are small computer chips attached to electric ribbon and, sometimes, encased in shrink wrap. To the untrained eye, they look like regular wiring. Assembled and coded from perfectly legal materials that can be purchased online, they often can be installed in seconds flat, simply by unplugging a cord and inserting a different one. There’s even a universal key that unlocks most older pumps, making placing the things even easier.

“We’ve got to get rid of those universal keys,” State Representative Mary Ann Perez, from Pasadena, who co-authored new anti-skimmer legislation this session, told us over the phone. “Texas didn’t have laws in place to adapt at the same pace as criminals.”

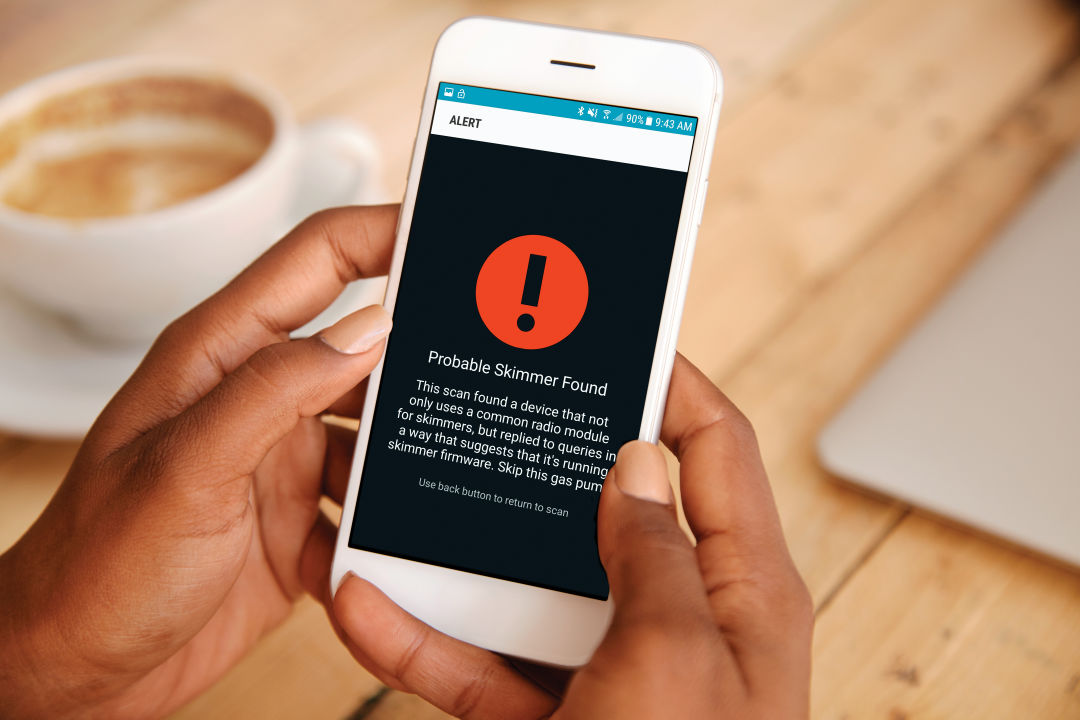

Tools like the Skimmer Scanner app help, to a point.

That’s for sure. Just a few years ago, skimmers had to be removed by hand for criminals to retrieve data, but today they can use Bluetooth and SMS technology—yes, text messaging—to simply send the information to themselves burner-phone style. “They don’t even have to be in the same city,” Miller says, “not even the same country.”

Around 1,400 skimmers were reported in Texas between December 2016 and November 2018, with fewer than a hundred of those devices discovered by law enforcement. A single undetected skimmer can make between $15,000 and $60,000 in a week, as Sgt. Headley testified.

While individual victims have to deal with the hassle of getting the money refunded and securing new cards, it’s the banks and credit unions, which have gotten very good at nipping suspicious charges in the bud, that nevertheless bear the brunt of these crimes. Last year multiple Texas credit unions reported losses in the vicinity of $200,000 due to skimming, whether in direct hits or costs incurred fighting fraud.

This city’s freeway layout is a major reason criminals have targeted us, according to Crime Stoppers CEO Rania Mankarious. “The way Houston is physically structured, you jump on any highway ... It’s very easy to get in and out.”

So far the gas stations themselves haven’t been held accountable for these crimes, although local media and sites like Nextdoor share hot spots to avoid. That is set to change, though, on September 1, when three new state House Bills passed this session—2945, 2624, and 2625—are signed into effect.

The new laws will implement best practices for gas station owners—upgrading pumps, performing routine checks—while instating penalties for those that fall short. They’ll also establish a new “payment fraud fusion center” in Tyler, which will facilitate coordination between agencies. “You’ve got multiple jurisdictions,” says Detective Colby, “chasing the same people across the state and country.” Meanwhile, for the first time it will be possible to prosecute criminals in any Texas county where they’ve planted skimmers, and people found in possession of counterfeit cards will face new penalties.

Typically skim artists will buy as many gift cards as they can until a card is shut down. They may get money orders, try to hit a bank account’s maximum withdrawal limit, or simply use a card to fill up tanks of gas to resell. I imagine my personal thief is riding through New York in a taxi, applying lip gloss from the pharmacy, wearing (ugly) shoes purchased at Nordstrom.

There are ways for consumers to guard against skimmers—skipping pumps located out of sight of the clerk, using credit cards instead of debit cards, looking for signs of tampering, using the Skimmer Scanner app, and filling up at stations with new skimmer-blocking pumps, among them. I for one always take the precaution of paying inside, at the counter. That’s the only way to be completely safe, right?

“Well now, we have found skimmers inside too,” says Miller. “It’s rare, but you should just pay in cash.”