Finding Home a World Away: Central America

Image: Michael Starghill

Devani Gonzalez

Mexico

In 2019 Gonzalez traveled to Washington, D.C., as Democratic congresswoman Sylvia Garcia’s guest, to hear President Donald Trump give the State of the Union address. Garcia invited Gonzalez for a reason: to highlight the plight of America’s DREAMERs who, under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, are able to go to college and work—for now.

Gonzalez has been in the U.S. since she was 7 years old, arriving here in 2003 with her family, who settled in Galena Park. “I don’t remember much from when I was a child living in Mexico,” she says. Currently enrolled at San Jacinto College, where she’s pursuing an associate degree in applied science and paralegal studies, Gonzalez dreams of becoming a police officer, of giving back to her community through public service. But her future is uncertain because the DACA program’s future is uncertain. “At the end of the day,” she says, “we just want a better future.” —EH

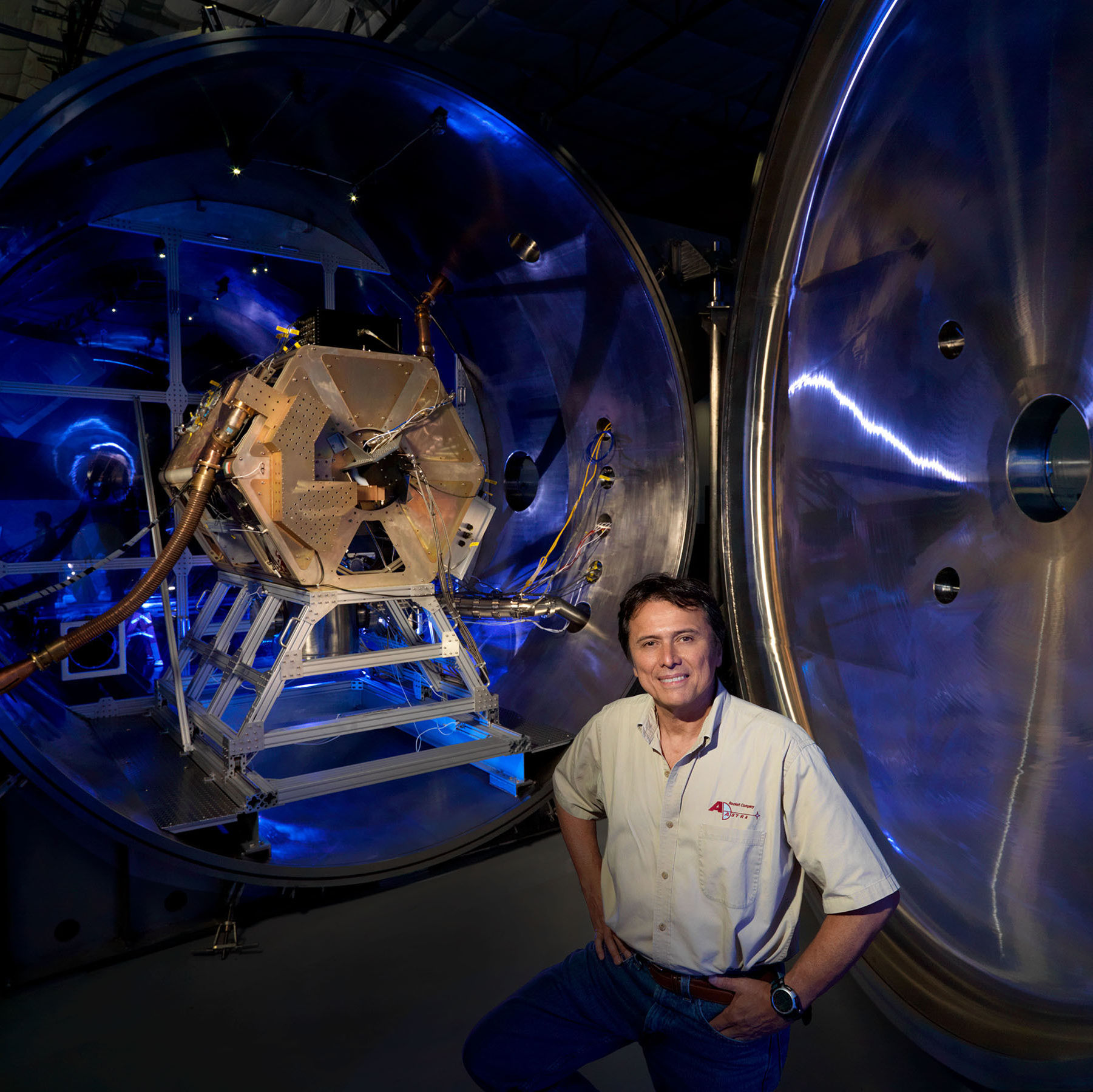

Franklin Chang Díaz

Franklin Chang Díaz

Costa Rica

Chang Díaz—who was named after FDR, his grandfather’s hero—knows his childhood dream to explore the cosmos wouldn’t have come true had he not been welcomed to America as an 18-year-old Costa Rican who didn’t know a word of English back in 1968. He went on to earn a Ph.D. in physics from MIT and, in 1986, become the first Latin American NASA astronaut to visit space. “I’m indebted to this society for all the opportunity that I’ve received,” he says today, “and I’ve been trying for the past 50 years to give back.”

After seven space missions, Chang Díaz retired from NASA in 2005 before founding the Ad Astra Rocket Company in Webster, where he’s developing advanced rocket tech that he hopes will help make human colonies on other planets a reality. He envisions a future, he says, in which humanity will work together to become a spacefaring, multi-planet species. In 2012 he was inducted into NASA’s Hall of Fame. —SE

Image: Thomas Shea

Marcelino Cantu

Mexico

"My brain didn't help me a lot," says Cantu, when asked why he ditched school in Mexico to cross the border into Texas back in 1974. Soon afterward he joined his brother as a busboy at the posh Brennan’s of Houston, and he’s still there today, 46 years later, serving as the Midtown restaurant’s senior captain and leading its waitstaff. And the truth is, his brain is invaluable. Cantu remembers everything from key dates to drink orders, one reason guests specifically ask for his section when reserving a table. Another reason? He’s warm and personable. The only thing he ever wanted, he says, is to have a job that could support a family. And he’s succeeded: His two adult children live locally with their own families. “I’m very proud because they live very nice,” he says. “It’s the reason I feel good.” —TM

Flor Marquez

El Salvador

A few years ago, when Marquez’s family refused to cave in to extortion from local gangs, she began getting threatening calls at the hospital in El Salvador where she worked. She and her husband scrambled to put together enough money for Flor, their two children, and their two grandchildren to make the dangerous 15-day trip to the U.S. Her husband, they decided, would stay behind in El Salvador for the time being.

In 2018 mother and son left home, hoping to reach Marquez’s daughter, who was already living in Houston. When they reached the border at Reynosa, Mexico, she and her son turned themselves in. They were transferred to a detention center in San Antonio, where they were kept for two weeks while the border patrol investigated their story before Flor’s daughter was allowed to take them to Houston.

In May 2018, with the help of a pro bono lawyer, the entire family was granted asylum. Tragically, her husband passed away from illness back in El Salvador just four months later. Despite all the pain, Marquez, who now works at a Houston-area shipping plant, is filled with hope for her son’s future and glad to be living a life without fear. “I’m happy to be somewhere where we’re safe and can prosper,” she says. —SE

Daniel Anguilu

Mexico

Hop the light rail in Houston, and Anguilu might be your driver—the coolest driver ever. Anguilu not only works for METRO, he’s also a street artist whose incredible murals—featuring modern interpretations of Aztec creation and water and bird stories inspired by his heritage, among other things—have appeared on over a hundred buildings across Houston. Anguilu actually learned to communicate with friends through graffiti, he explains, before he could even speak English. A few years after he arrived in Houston from Mexico City, at age 12 in 1991, a friend got him into graffiti, and they began painting buildings and trains in the Southwest and East Side areas of Houston. “There wasn’t a lot of talking involved,” he jokes—and, yes, it was pretty much illegal, but it also allowed him to develop as an artist.

Today Anguilu is renowned for his artwork, which has been featured at the Mexican Consulate. He only paints with permission and, mostly, by commission. It was in 2008 that, after traveling to numerous countries to paint, he joined METRO. He finds beauty in everyday things, including his day job, which he’s happy to note “isn’t damaging to the environment.” And he relishes the opportunity to share his vision with others. “As a native we’ve always moved around this land, our land, since the beginning of time. I don’t know if people ever think about—how does it look from someone who looks at the world in a completely different way? For me, to be able to paint and have a platform to explain to people how I see the world is beautiful.” —GK

Gislaine Williams

Image: Michael Starghill

Gislaine Williams

Honduras

Williams’s mother grew up in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, cared for by a single mother of five. From age 9, Williams says, her mom “started working, helping my abuela in restaurants or cleaning houses.” Despite the hardship the family faced, her grandmother always valued education, and Williams’s mom, aunts, and uncles all went on to get college degrees.

One evening Williams’s mom went out dancing and met a man from Madras (now Chennai), India, who was living in Honduras teaching English. They got married and had Williams in 1986. When she was 6, the family moved to Texas. While her dad got a job as a teacher with Fort Bend ISD, her mom’s education didn’t transfer over, so in the beginning she cleaned houses. “Both of my parents wanted me to have that American Dream,” Williams says. “They wanted to bring me here for a better life, to get a good education, to have opportunities.”

Williams considers herself lucky to have landed in Fort Bend County, where her shared Honduran and Indian heritage barely warranted mention. “It was already a pretty diverse place,” she says, “and so it was pretty easy to kind of fit in.”

Today Williams, who got her bachelor’s degree at Rice and her master’s in social work from UT, is the community relations director at the Alliance, which assists refugee women, immigrants, and underrepresented communities in Houston.

Over the years Williams has visited family in Honduras, but lately things have gotten so bad there, she says, that her grandmother has told her and her mother to stay away. She doesn’t have a family member living there who’s been unaffected by the country’s gang violence. Meanwhile, it’s near impossible for her Honduran relatives to get visas to visit the U.S.

“It’s really sad,” she says, “because it means we’ve missed things that have happened—weddings, funerals, babies being born. It’s really kind of heartbreaking to not be able to go there. Also, I recently got married, and except for my grandmother, none of my Honduran family was able to come.” —CM

Pascual Callejas Ramirez

Mexico

Ramirez was born in a rural area outside Querétaro, Mexico. “My parents grew up with no running water, dirt floors. They didn’t have access to public education. There was very little work. So they saw their situation and thought they didn’t want to raise a family there.” In 1998, when Ramirez was still a baby, they crossed the Rio Grande with their three children, eventually arriving in the small central Texas town of Mason.

Because the family was undocumented, fear was ever-present. They didn’t travel much except for school trips and functions. “We never knew if my mom or dad was going to come home,” Ramirez says. Nevertheless he thrived, excelling in school, graduating at the top of his class, earning DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) status his senior year of high school, and winning a scholarship to Angelo State University. He graduated from college in just three years, double-majoring in political science and Spanish, before moving to Houston in 2018 to take a job as a legal assistant with Catholic Charities.

Ramirez loves working and living independently here in Houston. He wants to continue to serve the immigrant community, and perhaps one day become an immigration attorney. But with the DACA program—which has allowed more than 700,000 immigrants to live and work here legally—landing in front of the Supreme Court, probably sometime this spring, he’s uncertain of the future.

“It’s very nerve-wracking to know that everything that my parents have sacrificed for, everything they’ve worked toward, could be destroyed. I try not to think about it too much. I try to be hopeful, but it’s hard. We can rally, and we can advocate, and we can inform, but I can’t go to the polls. I can’t vote.”

And if the program is halted? “I can’t even imagine what would happen. Without some sort of way to work and make a living, I wouldn’t know what to do.” —CM