How Yellow Fever Shaped Houston in Its Infancy

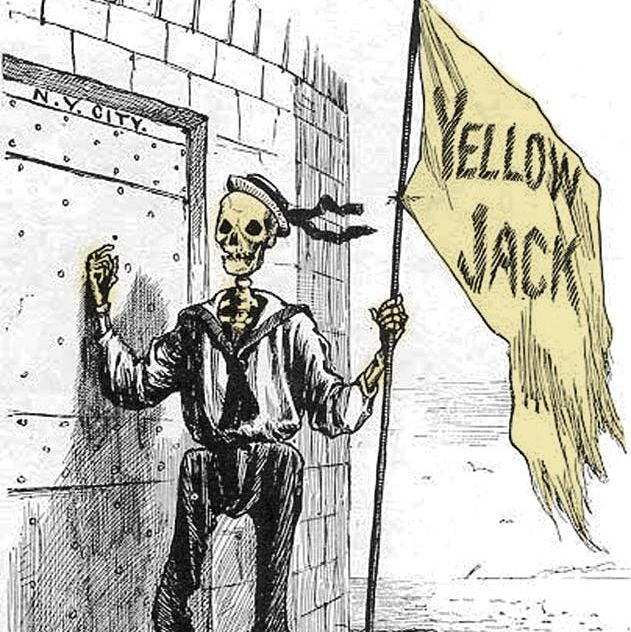

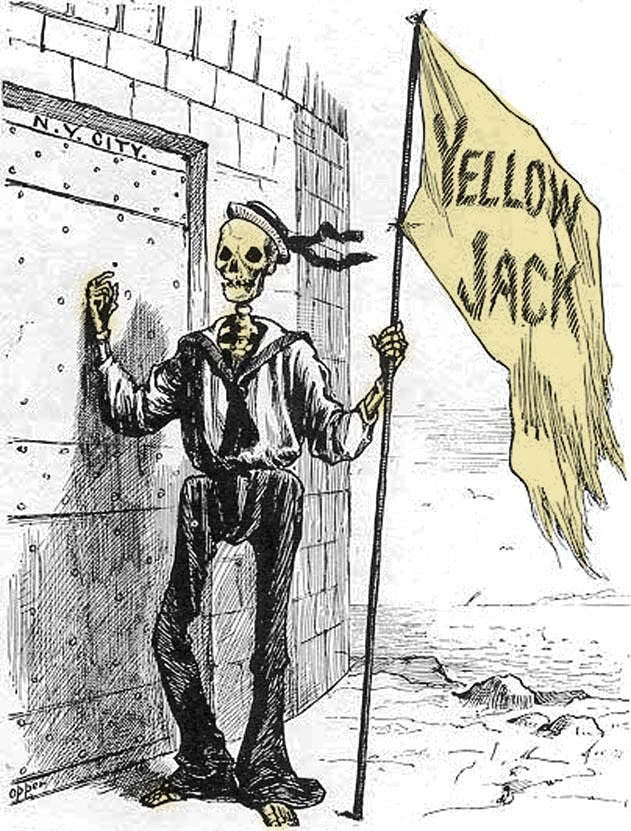

Image: Fair Use

In the mid-19th century, Houston was still barely discernible amid the swamps and grasslands it was erected upon when it became the capital of the nascent republic of Texas, with the promise of becoming a hub of both trade and political power, a city strapped to a rocket. Nothing could stop this fast-growing town—except for yellow fever, a then-mysterious virus that struck without warning, killing one in five of its victims. The disease proved fatal to hundreds of Houstonians over the course of 30 years, bringing the Bayou City to its knees.

“Sickness, sickness all around and many deaths,” a Houston diarist wrote at the time of the 1839 outbreak. “This is an awful disease and does not seem to be understood by the physicians.”

The virus first arrived in North America during the 1600s with the Atlantic slave trade, when infected female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes laid eggs in stagnant water and in cotton bales on ships, and bit and infected slaves. But it didn’t reach the Gulf Coast until the 1830s, after native mosquitoes transmitted the spreading disease from infected hosts to non-carriers. In the summer of 1839, two years after being named the capital of the Republic of Texas, Houston saw its first outbreak of yellow jack.

“That’s the reason why our capital is in Austin and not in Houston,” says Catherine Troisi, an epidemiologist with UT Health. After a brief sojourn in Houston that summer, then-Republic President Mirabeau B. Lamar moved the capital to Waterloo, later renamed Austin, to escape the epidemic.

Image: Fair Use

At first few people connected the disease’s transmission to mosquito bites, and physicians instructed Houstonians to try a number of useless methods to stop the virus’s spread. The air filled with acrid smoke from the burning of tar and sulfur, on doctors’ orders, in misguided efforts to clear the “bad air” thought to be the culprit, but people continued to fall ill. The sick went into quarantine. People shot off cannons hoping to clear the infection out by force.

“It was a bad time, and people were very afraid,” Troisi says. “But they thought it was spread through the air or person to person, so the measures that they took to protect themselves didn’t work.”

One Galveston doctor, Ashbel Smith, even swallowed the vomit of infected patients to find out what would happen—he didn’t get sick. The dead piled up so fast they were buried in long trenches and without any ceremony. A twelfth of Houston’s population died before the cooler months provided a reprieve.

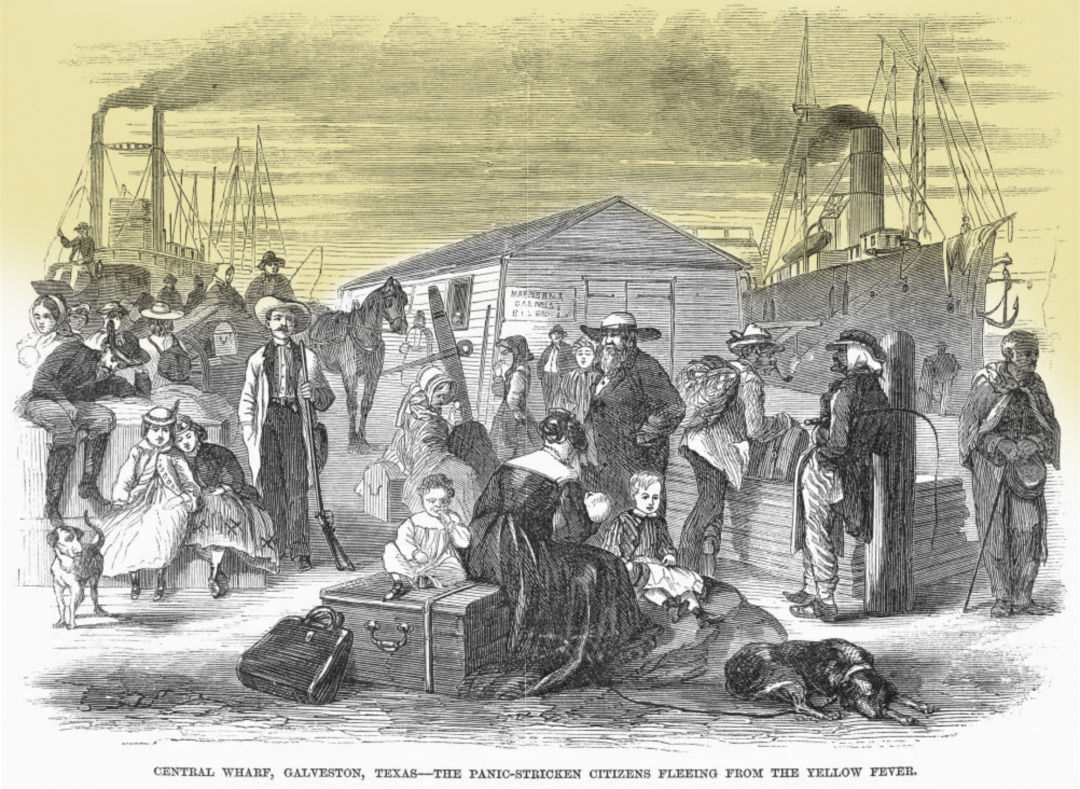

The epidemic returned in the summer of 1843, and again and again over the following decades, with outbreaks in New Orleans usually triggering more on the Texas coast and then creeping inland. The worst came in 1867, as Houston, then a city of about 6,000 people, was becoming the military hub of the state thanks to a growing influx of federal troops stationed here during Reconstruction. That summer 492 Houstonians died of yellow fever. Even Sam Houston’s widow was buried hastily just outside the city.

By then the theory of mosquito transmission hadn’t been proven, but it was gaining traction. (Although Cuban physician Carlos Finlay would lead a controlled experiment within a decade in which the same mosquitoes bit infected patients and then a healthy, willing subject, it would take until 1900 to confirm that mosquitoes were the disease vectors.)

However, when yellow jack returned to Galveston in 1870, Houstonians were savvy. The city employed a strict armed quarantine, which kept infected islanders from coming to town. Sure enough, the scourge didn’t penetrate the city as in years past, and from then on quarantines were put in place whenever yellow jack showed up on the coast, helping to curb the spread.

Along with that, Houston’s evolution into a maturing commercial hub by the dawn of the 20th century brought improved drainage systems. As the city built more roads, ditches, and channels, it raised itself up from the swamp enough to keep the mosquitoes from doing grave damage to the population.

Yellow fever still exists in parts of Africa and South America, and people planning to travel to those higher-risk locations should receive the vaccine, which has been available since the 1940s. Scientists say the virus can always return here, but we’re now well versed in mosquito-borne illnesses in Houston: just use that bug spray vigorously. And even though Austin is still the capital of Texas thanks to yellow jack, Houston has managed to do just fine being the energy capital of the nation.