Pioneering Dadaist Jack Massing Has Not-So-Absurd Plans for the Orange Show

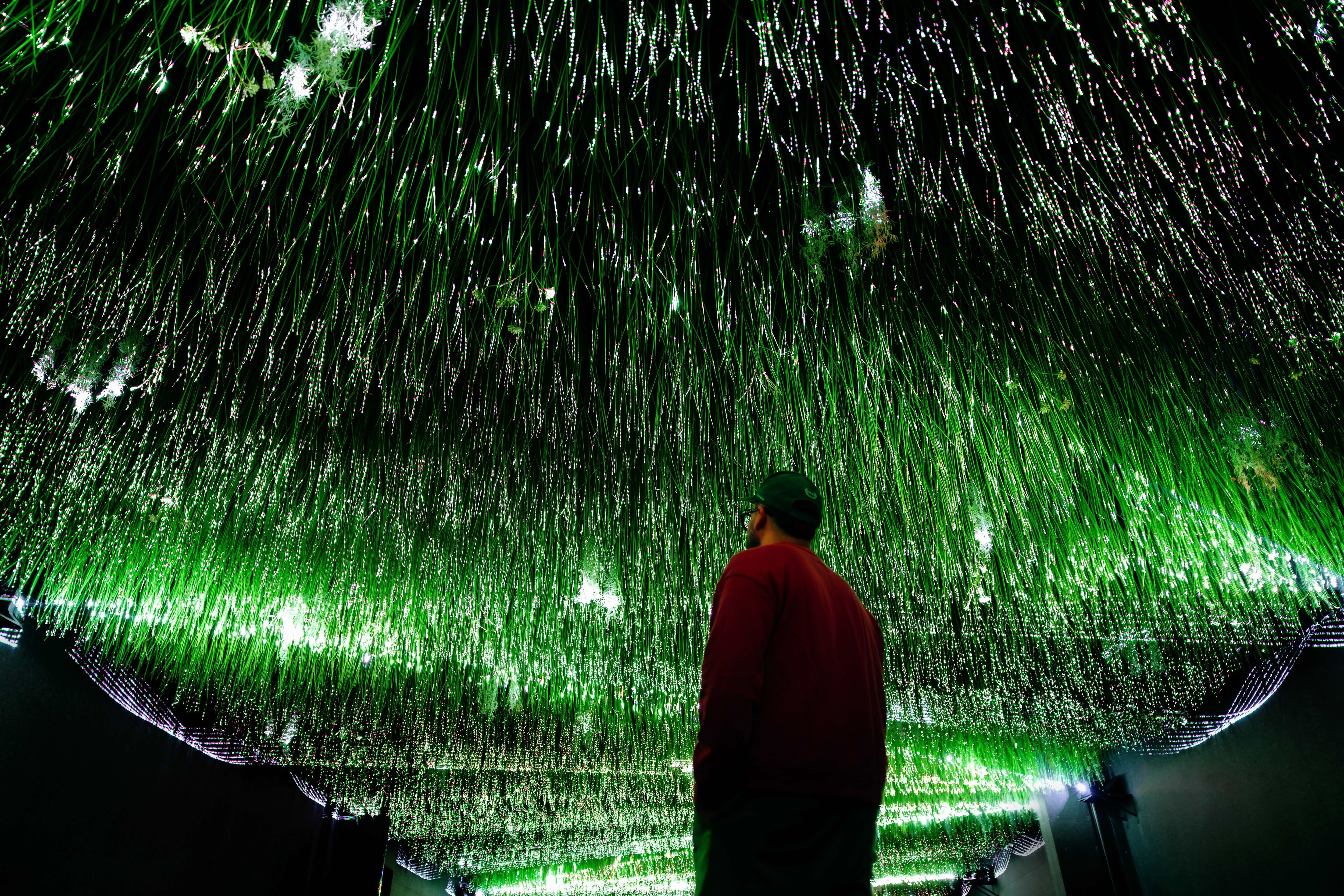

Image: Courtesy of Sean Miller

The Orange Show Center for Visionary Art's executive director, Jack Massing, kissed a lot of people in May 2008—and not always on the face. This isn’t a scandalous revelation. It’s immortalized in Nothing To It, a recording of an evening’s performance at Massing’s alma mater University of Houston. Titled Kiss Piece, Massing and his late creative partner, Michael Galbreth, set out to smooch every member of the Wortham Theater Center audience. If it all sounds incredibly silly, then congratulations. You understand what the Art Guys were all about.

The formal name for Massing and Galbreth’s collaboration and meta project ran from 1983 until Galbreth’s passing in 2019. “We tried to do everything we could under the guise of art and share our production and develop projects that we both were really interested in for whatever reason,” Massing says. “We jumped around too much. I think we just went from one idea to the next a little bit too rapidly, because it was fun.”

Chasing curiosity and creativity has always been his goal, even from childhood. Born and raised in Tonawanda, New York, Massing grew up with a father who worked as both a chemical engineer at Union Carbide and a professional artist. His dad, who had an art studio in the basement, would often invite his children into his world, taking them to gallery shows and museums after hours. Early exposure, combined with the freedom to explore artistic topics on his own, led Massing to find inspiration in French artist Marcel Duchamp and his work in the avant-garde sensibilities of Dadaism, an early-twentieth-century movement characterized by absurdity, randomness, experimentation, and protests against capitalism and war. “I don't think I sat down and studied it to try to be like them. I think their tone and their ideas struck me as correct, so I just carried that with me,” he says.

New York’s Earl W. Brydges Artpark State Park, however, was “the most influential thing” to his then-burgeoning arts career. He and his father would visit Artpark together, where they’d meet artists working on their latest projects. “If the public came by to talk, they couldn’t shoo them away. They had to be accessible,” Massing says. “…I was looking at their work and just thinking, ‘Oh my gosh. I didn’t even know this was possible.’ I got super jazzed, and so did my dad.”

Massing signed up for classes at Niagara County Community College (NCCC) because the school had a close relationship with Artpark, often setting students up with internships. He worked there for three summers, getting to know the artists who created out in the open and making connections that he’s maintained throughout his life. Working with Artpark would lead to opportunities to assist artists in Seattle, Washington, and Amarillo, Texas, as well as at home in New York state, prompting him to drop out of NCCC to absorb all he could about the art world. “[Artpark was] where my mind was changed, and I met a lot of really influential people to me to this day, who were dabbling in everything that you can think of: land, art, sculpture, film, performance,” Massing says. “It was just an amazing thing for me.”

When his father moved the family to Spring, Texas, in 1979, he tagged along to help and subsequently decided to stay in Houston, enrolling in the prestigious Core Residency Program at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s Glassell School of Art, which opened that same year. Globally renowned sculptor and art professor James Surls, who taught at University of Houston (UH), dropped by Massing’s studio one day. The future Art Guy only lasted at Glassell for a year before running off with the Cougars and into the annals of art history.

Surls invited Massing to be part of an exhibition, and fellow art student Galbreth assisted with the hauling. Massing and Galbreth bonded over a disinterest in creating works made for the art market, preferring to play with ideas by stretching them into curious shapes. “When I met Mike, it was like two tuning forks together, working well, and we got really excited about talking about these different ideas, and it just worked,” Massing says. They formalized their Art Guys partnership in 1983 with their first of many video works, in which they dipped their hands in paint and shook them over a canvas to create the aptly titled The Art Guys Agree on a Painting. “Conceptual art is built upon ideas, not always complicated, sometimes simple. Sometimes they develop into complicated ideas,” he says. “But with that handshake, we became the Art Guys through a funny give and take and joking around, talking about it, which grew into a very complicated idea.”

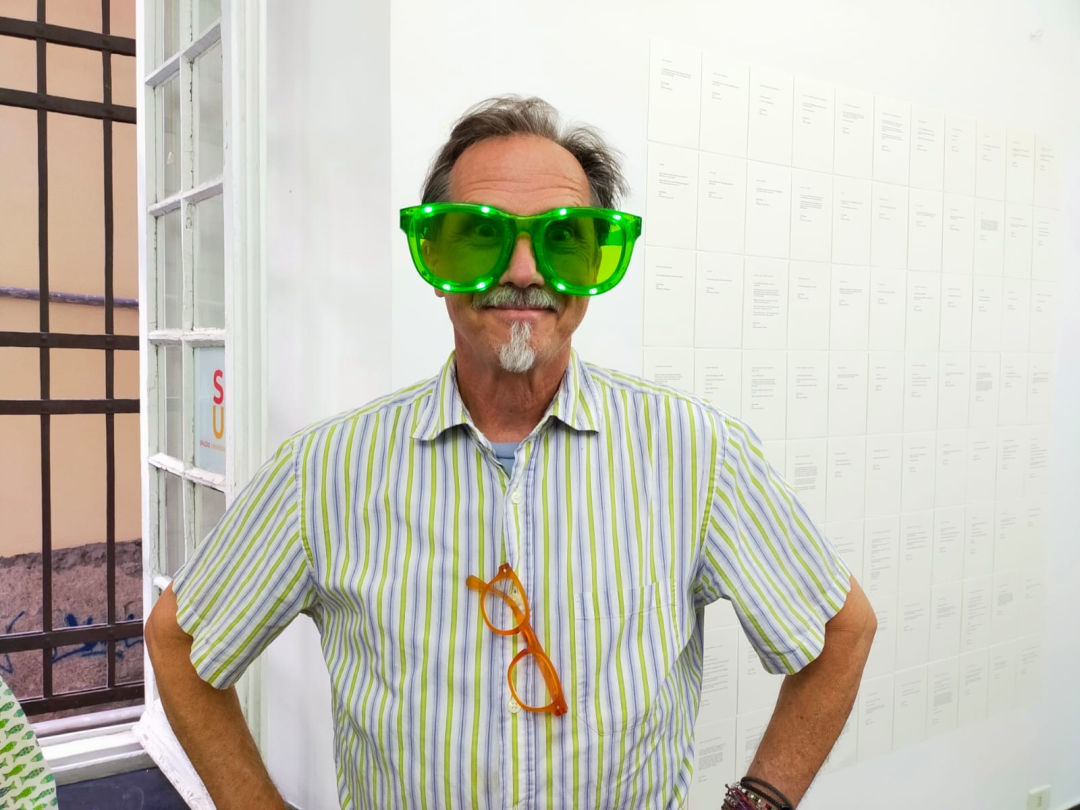

Image: Courtesy of Mark Seliger

This simple sketch evolved into a complex, decades-long project embodying the anarchic spirit of Dadaism. The Art Guys weren’t video artists, or visual artists, or performance artists, or even sound designers: Depending on the media and the ideas they were exploring, they were all of the above and more. Kiss Piece, for example, could only be performed live, as literal smooches were administered by Massing and Galbreth. Behavioral art events, similarly, had to take place in specific locations at designated times. For Blue Sunday, Massing and Galbreth stood in front of Houston City Hall on a Sunday, selling items that were prohibited from store shelves on that day due to Texas’s draconian blue laws. For Stop N Go, the duo worked a 24-hour shift at a convenience store in the Museum District.

Plunging through the depths of the Art Guys’ portfolio shows not only an almost improv-like fascination with saying, “Yes, and” to a suggestion and batting it around from there, but also a sincere love and appreciation for the banal—their work revels in discovering art in the everyday. “Art is not what it is. It's what it could be or what it can be, and people that are making things are making things to discover what more is out there,” Massing says. Among the performances in Nothing To It, there includes a fully choreographed musical number exalting plywood; the men silently adorning one another with repurposed wrapping paper, bows, and ribbons; plus soundscapes designed with packing tape.

A career devoted to finding beauty in life itself and celebrating all its contradictions, mundanities, and absurdities made Massing an ideal fit to take over as executive director of the Orange Show Center for Visionary Art in 2024. Founded in 1980 as the Orange Show Foundation, the site originated to preserve local post office worker Jeff McKissack’s folk art installation, dedicated to his favorite fruit. Since then, it has grown to include the Beer Can House (exactly what it sounds like) in the Heights; the folk art–centric Smither Park; the beloved Art Car and Art Bike Parades; and annual exhibitions of cutting-edge art that may not suit a more traditional gallery setting. Even before ascending to directorhood, Massing partnered with the Orange Show on multiple occasions, citing it as a space that inspires people and opens them up to new ideas. “They let their guard down, and they realize that you can make anything out of anything, and it’s fun and liberating, and it’s an exercise in being human,” he says. “We don’t do that much anymore, because we’re inside of a different bubble where we’re trying to be productive…financial responsibilities rather than artistic responsibilities.”

In addition to his passion for the arts, Massing, who once considered studying forestry, has a fascination with the natural world and a commitment to ecological preservation, environmentalism, and sustainability, which he incorporates into his art and leadership. The Orange Show will enhance its recycling and reuse policies—Massing believes this helps humans discover their own creative voices (he believes that viewing the rejuvenation of a material may inspire reflection on the rejuvenation of the self). Massing also recently debuted Waste Stream at Buffalo Bayou. Dubbed “the performance without an audience,” the show involved attaching a 12-foot plastic skeleton to the back of a kayak and collecting plastic waste from the water. The detritus was repurposed into an installation now on display at the Silos at Sawyer Yards, part of its Sculpture Month 2025 exhibition; Massing will later recycle it. Cleaning up litter and microplastics, to him, is a form of sculpture, comparable to the subtractive process of carving a figure out of marble. “I think ‘woke’ is really important right now. We need to wake up and see what’s happening around us,” he says. “Unfortunately, the political divisiveness has made something that’s an attribute seem ugly. I’d rather be woke than broke.”

Image: Courtesy of Fleabilly

There’s a direct line between loving the planet and the people on it that’s endemic to Massing’s works. Claiming of the oft-contradictory state, “Texas is hyperbole with a wink,” Houston has provided him with what he sees as one of the nation’s most enthusiastic and supportive visual arts scenes. “It’s amazing, the camaraderie here, and the attitude from one artist to another, the generosity and the helpfulness that they share here is unmatched,” he says. “I don’t know any other place that exists that is so open and sharing, at least that’s my perception of it…I think it has to do with the Southern hospitality meets the West expansion idea.”

Having lived and worked in the thick of it all since 1979, Massing has enjoyed a truly unique opportunity to both observe and directly shape the local arts over the past few decades. He’ll also oversee an upcoming capital campaign for Orange Show, aiming to expand the organization’s physical campus and, subsequently, increase the number of opportunities for artists of all backgrounds to learn, play, and explore along the way. When he reflects on his journey, the people he has met and the places he has been, Massing likens himself to Tom Hanks’s Oscar-winning character Forrest Gump. “I think the Orange Show, working on this as a project, is kind of a crowning jewel in my life,” he says. “It’s already an amazing, cool place, but we’re expanding…I’m dedicated to trying to make that the best thing that I can.”

That said, there’s still so much more to Massing than a visionary artist overseeing a visionary art organization. “I really like dogs, and I visited Europe a couple times. And popcorn is one of my favorite foods to eat as a snack,” he says.