The Deliberate Flooding of West Houston

It was Friday, September 15, nearly three weeks since Hurricane Harvey, and there were still fish swimming in the greenish-black waters of Barry LaCoste’s backyard pool. “If they’re alive, we’re taking that as a good sign,” he joked. “It means the water can’t be that toxic.” He seemed surprisingly jovial for a man who’d spent the past few days tearing out most of the first floor of his home and dragging it all out onto his lawn, where his family’s possessions sat in ruined heaps taller than he was.

One colorful jumble contained his 2-year-old son Christopher’s mold-covered toys. On a nearby water-damaged bookcase, a family photo album sat spread open in the sun. The debris piles lined both sides of the walkway leading to his home in Memorial Thicket, an Energy Corridor neighborhood where every single home was still under floodwaters as of a few days prior.

LaCoste’s family also had lost both of their cars as the entire first floor of their home filled with waist-deep water on Monday, August 28. As with many of the houses here in West Houston, it had never flooded before. And it didn’t flood during Harvey—only afterward, when the nearly full Addicks and Barker Reservoirs were released in a late-night panic, their waters quickly swamping downstream neighborhoods along Buffalo Bayou.

Along with 80 percent of Houstonians, LaCoste didn’t have flood insurance. And as one among many locals recovering from the recent oil and gas downturn, he’d been unemployed for two years before finally finding a new job in April. Money was already tight before Harvey.

As he surveyed the wreckage of his own and his neighbors’ homes—with their flooded-out cars and lawns overflowing with saggy piles of soaked furniture and drywall—LaCoste wondered how long it would take people like him to rebuild. He estimated he’d need $250,000 alone to restore his home, which had sat under flood waters for two long weeks before finally drying out, to livable conditions. But more importantly, he wondered if he should.

“If we can’t be reassured that we’re not going to get flooded again, we’re not going to spend the money,” he said. After all, now that a precedent for handling the over-saturated reservoirs had been set, who was to say these neighborhoods wouldn’t be sacrificed again, should Houston face another catastrophic flooding event?

And this was only one of the questions that had gone largely unanswered in the wake of the deliberate flooding of the Memorial and Energy Corridor neighborhoods southeast of the city’s two main reservoirs, where nearly 200,000 Houstonians live. Residents also complained that a lack of communication on the part of city and Harris County officials gave them no real understanding of the impact this would have on neighborhoods along Buffalo Bayou, and no time to make decisions that would have allowed them to save their cars and other possessions.

“Most of our neighbors didn’t know. It wasn’t on my TV. It wasn’t on our social sites. It wasn’t on my phone alerts, even though we got flood alerts every 15 minutes,” said LaCoste, who’d ended up evacuating with his terrified toddler and wife on August 28, the morning after the reservoirs were first released. No evacuation orders had yet been given, and yet there they were watching their world go under. They grabbed one toy and some milk for Christopher and a few items of clothing, and escaped.

“That’s the biggest complaint from anyone I’ve heard,” he said. “We weren’t given any time to save anything.”

Barry LaCoste's Memorial Thicket home sat underwater for two weeks.

Image: Max Burkhalter

On Friday, August 25, Hurricane Harvey made landfall near Rockport as a Category 4 storm. The next day, it was downgraded from a hurricane to a tropical storm as it hit Houston. At that point, many Houstonians experienced a false sense of relief.

Starting on Sunday, August 27, the storm—which had strengthened after a brief circle into the Gulf of Mexico—dumped a torrential 50 inches of rain on the city. And by midnight, the two reservoirs keeping Houston from experiencing catastrophic flooding could no longer contain the rising waters within; uncontrolled releases were already occurring at the edges of both dams.

So the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers made the decision: Release the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs, intentionally inundating Buffalo Bayou downstream and the thousands of houses on either side of its quiet banks. “If we don’t begin releasing now, the volume of uncontrolled water around the dams will be higher and have a greater impact on the surrounding communities,” said Col. Lars Zetterstrom, Galveston District commander for the Corps, in a press release. He also argued that no matter what they did, the excess water was coming for Buffalo Bayou one way or another.

“It’s going to be better to release the water through the gates directly into Buffalo Bayou as opposed to letting it go around the end and through additional neighborhoods and ultimately into the bayou,” said Zetterstrom. Such “uncontrolled” releases were even less predictable, and subsidence around the edges of the levees could lead to a failure in the dams. Such a breach, the Corps estimated, could affect 1 million residents downstream and cause $60 billion worth of damage.

By the morning of August 28, homes in Memorial and the Energy Corridor that had never once flooded were filling with five feet of water. The Harris County Flood Control District wouldn’t release a statement aimed at area residents until late the next day—August 29 at 10:45 p.m.—that briefly warned: “Controlled releases on Addicks and Barker Reservoir increase flooding threat along Buffalo Bayou.”

A mandatory evacuation order for the 4,000 affected homes wouldn’t be issued by Mayor Sylvester Turner until the following Saturday, September 2, long after the waters had swamped the area. It followed a voluntary evacuation order issued on September 1.

City officials told the Houston Chronicle on September 18 that the Corps had downplayed the extent of the expected flooding; they only anticipated it in the streets, not any homes. This communication breakdown appears to be the main reason an evacuation order wasn’t called for sooner; on September 26, Mayor Turner told the Texas Tribune that, “No, the communication was not good,” when asked how the Corps had handled conveying this information to the city.

“They told us they were going to release water from the reservoir,” Turner told Houstonia by phone on October 11. “Initially, it was 4,000 cubic feet per second from Addicks and 4,000 from Barker. That was what they posed initially, then they made a decision to increase that amount—but they didn’t tell us first; they simply did it. We found out the next day. It certainly would have been helpful if we had known that they were going beyond [that initial amount]—and when they were going to do it and what the effects of that would be—but we simply didn’t have those details.”

Leading up to the decision, said the Mayor, communication had been better. “We were talking with the Corps every day during the day—several times during the day—because we wanted to be kept abreast. We were having these news reports twice daily, getting as much information as we could, so we could relay it to the general public.”

But then, overnight, communication ceased; Turner’s office wouldn’t find out about the flash-flooding in West Houston until the next morning—at the same time residents were waking up to water in their homes. “They made the decision unilaterally,” said Turner. “It was a nighttime decision without any forewarning.”

For his part, Harris County Judge Ed Emmett also could have called for evacuations of the area earlier, but did not; Emmett was unable to comment on this to Houstonia pending a lawsuit—one of a slew of state and federal suits that have been filed against the City of Houston, the Harris County Flood Control District, Harris County, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers seeking to hold the various agencies accountable for the destruction downstream.

During the two weeks following the reservoir release, two elderly residents who couldn’t escape, Cathy Harling Montgomery and Robert Arthur Haines, would be found dead; people in homes and apartments alike would watch their cars, clothing and personal possessions consumed by floodwaters; residents would chase away looters; rescues would be conducted by civilians; in many areas, the stinking, hazardous waters would refuse to recede as rotting garbage and debris piled up. And residents would wonder why they’d been deliberately flooded, then left without answers—and how on earth they could keep this from happening again.

For 10 days, Katie Mehnert's Nottingham Forest home was only reachable by power boat.

Image: Max Burkhalter

"We thought we were safe," said Katie Mehnert. “For years, we were told our homes were safe. I sit 90-some-odd feet above sea level.” Mehnert is a resident of Nottingham Forest VIII who, like Barry LaCoste, saw her own, formerly flood-free house consumed by the overnight reservoir release. For 10 days, her home was unreachable except by power boat; she got a staph infection wading through the waters there.

When we spoke with her on September 19, Mehnert was still infuriated by the way the entire situation had played out. “The whole system failed,” she said, “telling us to stay in place and then evacuating people after the fact.”

Turner later told Houstonia that a mandatory evacuation wasn’t considered until first responders realized that power was still on in many places. “The firefighters came to me and said as they were going to check on people in that area, it seemed like there was some static or electricity in the water,” said Turner. “The power was on in some of these houses; they could feel some tingling in their boats, and they were concerned a fire could erupt with people in their homes. It was a public health hazard.”

Sure enough, a home at Memorial Drive and Kirkwood caught fire on September 2; videos show firefighters wading through floodwaters to battle the flames. “The firefighters were having a very difficult time accessing that home,” said Turner.

More frustrating, Turner said, was that many Memorial residents hadn’t heeded his call for a voluntary evacuation. “It was getting to be too taxing on the first responders for them to be assisting in providing water or food to people who were electing to remain in their homes,” he said. “Our resources were being stretched too thin.” There was the entire rest of the city outside of West Houston to contend with too, after all.

“Sacrificial lambs” was a commonly heard phrase in Memorial in the weeks after Harvey, on the streets among neighbors helping each other muck out homes, on the NextDoor and Facebook message boards. Everyone here knew the alternative—an uncontrolled release—would have been even more devastating. Everyone knew their homes had been destroyed so that others would have a chance. What no one understood was why there had been no plan in place for this catastrophic contingency, nor why official responses afterward were so sluggish.

“It was 11 days,” said Mehnert. That’s how long it took Mayor Sylvester Turner, Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo and Houston Fire Chief Samuel Peña to visit the heavily flooded neighborhoods of West Houston, where parts of Beltway 8 remained under 16 feet of water and major thoroughfares like Highway 6, Eldridge Parkway and Gessner remained impassable. Still, neighborhoods like Mehnert’s were accessible—and that’s where Turner and his team took their tour, on Friday, September 8, Mehnert at their side.

In the 11 days leading up to that visit, Mehnert, the CEO of energy firm PinkPetro and a community leader in her own right, had been hard at work helping organize neighborhood meetings, rescues, supply drops, security checkpoints, meal deliveries and other relief efforts. Throughout, she and others tried to draw officials’ attention to their still-flooded neighborhoods, where an overwhelming amount of trash and dangerous, sewage-thickened water filled the streets. Mehnert and others—including Greg Travis, councilman for District G, which covers most of West Houston—begged the Mayor to come visit, to see what they were dealing with firsthand, but the city’s attention was focused on parts of Houston that had already emerged from the floodwaters.

And as the garbage piled up, so did more questions: Why were there 300 trucks picking up debris throughout the city, but only two in the Memorial area? Where were the FEMA representatives? When would the reservoirs finally empty, the streets be cleared of debris? They didn’t know. (Later, questions from this publication to the Harris County Flood Control District and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers would go mostly unanswered.)

But for Mehnert, perhaps the biggest frustration was watching Turner tell Face the Nation on September 3, a day after finally issuing a mandatory evacuation order, that Houston was “open for business” and that, in West Houston, only 26 homes were still underwater. At the time, the number in Memorial alone was closer to 2,600. That the Mayor may have misspoken didn’t quell her frustration.

“This was an overwhelming situation for anybody to grasp, but to me you should say, ‘Hey, we’re coming,’” said Mehnert. “I just don’t think people understood the level of impact.”

Mayor Turner defended his office’s response to the situation. “We spent a great deal of resources—in fact, the city spent more resources in the Memorial area than in any other part of the city,” he told Houstonia. “In West Houston, all during the night, 24 hours a day, you had HPD, firefighters, FBI agents and others specifically assigned to that area to prevent people from coming in and looting.”

Regardless of how long it took him, personally, to visit, Turner disputed the characterization of his response as less than adequate, adamant that the area was not ignored. “Let me underscore: Those firefighters and police, their own safety was exposed because you had areas where power was still on and they were risking their lives every single day, 24/7, to protect the lives of people who elected to stay in that area,” he said. “Let me push back very hard on anyone who claims the city was not overly responsive to West Houston. The city didn’t flood West Houston. The city didn’t make the decision to release the water from the reservoir.”

The Barker Reservoir overflows onto Highway 6 at Briar Hills Parkway.

When Harvey hit, our local officials led a city in crisis with cool heads. They helmed a massive rescue effort, opened a network of emergency shelters, and kept the city informed on what the weathercasters were predicting, as the downpours continued. They were lauded for their efforts, and rightly so.

Indeed, the decision to release water from the reservoirs is considered by the vast majority to be the right thing to do in the moment. But that correct call was made after 70 years’ worth of botches and breakdowns on the part of city, state and federal officials—all of which culminated in the deliberate post-Harvey flooding of West Houston.

These failures can be traced to the inception of the reservoirs themselves, which were constructed after two massive floods, in 1929 and 1935, crippled Houston. The original 1940 plan called for three reservoirs, but by the time Barker opened in 1945 and Addicks three years later, funding had dried up. The third, dubbed White Oak Reservoir, was never built.

The Corps purchased the land the reservoirs sit on, but a lack of funding prevented them from buying the complete area that could flood if the reservoirs were to fill, something that at the time seemed nearly impossible. Today, development has encroached upon those areas, with master-planned communities built right up to the exact line of federal land. And over time, the nearby reservoirs, which are largely used as parkland outside of large rain events, were marketed to buyers as amenities. Many didn’t understand, and weren’t informed, that those neighborhoods could face grave danger in the event of another massive flood.

In 1995, the Corps issued a report following a March 1992 flood that set the previous record for flooding in the reservoirs, stating, “In the absence of a public awareness program, residents are likely to forget or ignore the flood threat.” The report recommended a variety of solutions, including buyouts of homes upstream and the creation of a flood warning system. And yet, as the Houston Chronicle noted when they rediscovered the decades-old report in early October, the authors also recommended these potential solutions “be terminated because of insufficient economic benefits to justify project modification.”

By 1996, the reservoirs had hit their 50-year life expectancies, and engineers for the Harris County Flood Control District proposed a $400 million plan to address the issue: While the Katy Freeway underwent a planned expansion, a large conduit could be built underneath the freeway to channel water from the reservoir out to the Ship Channel. It was never implemented, primarily due to cost, and Houston missed a vital opportunity to fix the problem.

Instead, the Corps began a series of band-aid fixes using what funds they had, including reinforcing the reservoirs’ earthen walls. Today, both are 20 years past their life expectancy.

Experts consider an ongoing project to update the floodgates to be an inadequate measure. And anyway, it’s been postponed—previously, due to the Tax Day Floods, and now Harvey. After all, the experts will say, the dams worked as designed during Harvey! There was simply much more water in the reservoirs than they could comfortably handle: a failure not of the reservoirs themselves, but of unchecked development in the area.

In 2009, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers listed Addicks and Barker as two of the six most-dangerous dams in the country. And yet seven years later, just before retiring in 2016, Mike Talbott—the former head of the Harris County Flood Control District who’d been at the department for 35 years—told reporters he didn’t see any major issues with the county’s storm-water infrastructure.

The Corps, which has been hampered by inadequate funding, had studied the potential impact of controlled releases of the reservoirs as part of their water-control manual, but the results were never shared with area residents. And in 2011, the Sierra Club brought a lawsuit against the planned segment E of the Grand Parkway, arguing that the new freeway and the resulting development around it would increase the load of the aging dams. The Houston Chronicle found that in private exchanges, local Corps employees agreed with this assessment, and yet their hydrology experts stated that the new freeway wouldn’t impact the reservoirs negatively. Construction went ahead.

“Every piece of concrete that’s poured upstream is going to have an impact on these reservoirs. Every square inch,” Richard Long, who oversees the reservoirs for the Corps, told the Chronicle in a story published last year. In that same piece, he predicted what would soon come to pass—that the Corps would have to “pull the plug,” purposefully flooding downstream neighborhoods to avoid the worst-case scenario. “We’ve got to make sure we protect the city of Houston as a whole,” he said.

A sign in Nottingham Forest at Broadgreen and Clear Creek warns of floodwaters at the rear of the neighborhood.

We met Greg Travis, the councilmember for District G—which covers most of Memorial and the Energy Corridor— near Wilcrest Drive and Lakeside Forest on an overcast morning. It was Monday, September 18, three weeks after the reservoirs were released. On one side of Lakeside Forest was a tony neighborhood of multi-million-dollar homes; on the other, a sprawling, three-story apartment-complex community. Heaps of sheetrock, insulation, carpet and other trash covered both areas in equal amounts.

Travis was wearing a wrinkled polo shirt, jeans and work boots. He apologized for his rumpled appearance, though he fit right in with his own tired constituents. He’d been out of town on city business when Harvey hit, but finally made it back to Houston once Bush Intercontinental Airport reopened—an additional source of frustration for area residents who wanted their councilman in the field and answering questions right away.

For the two weeks prior, Travis had been fielding calls from constituents on his personal cell phone and attempting to coordinate with officials on his City of Houston phone. We joined him as he drove the streets in search of trucks picking up trash—valuable information for the councilmember to convey to his district. The worst of the catastrophic flooding was over and most roads had reopened, though cleanup in the area had been hampered by a lack of solid-waste disposal services.

Travis was furious, he said, over the mounds of debris that still cover the majority of the yards and medians in his district. To him, it was yet another example of the city’s lack of preparedness and a frustrating continuation of the communication breakdown that had occurred in the wake of Hurricane Harvey. Harvey left behind an estimated 8 million cubic yards of debris; as of that Monday morning, only 400,000 cubic yards had been picked up.

We finally encountered a claw-armed, heavy-duty dump truck off Kickerillo Drive. It was the first one Travis had seen, and he greeted the driver—who’d come here all the way from Ontario, Canada—exuberantly. But it had been three weeks; why was this the first major movement toward trash pick-up Travis had so far witnessed in his district?

“They could’ve had these out here two weeks ago,” he said. “If you had 100 trucks in my area now, this would all be gone in two or three days. The moment the storm ended, you knew this was going to happen. Why didn’t you have it all arranged ahead of time? It’s not rocket science, it’s just organization. And you just have to plan ahead.”

As we watched, we saw that the claw arm didn’t extend all the way into the lawns, and could only pick up the debris closest to the curb. Travis sighed, realizing he was about to get a barrage of calls. Sure enough, 10 minutes after we’d left the neighborhood, one of his staff—director of constituent services and communications Mark Kirschke—called to report that residents were upset. Less than half of their debris had been hauled away; what were they supposed to do with the rest?

Kirschke had an idea: rent some Bobcats to push the remaining debris to the curbs. “Put it on my personal card,” said Travis. “We’ll figure the rest out later.”

On his City of Houston–issued phone were countless unreturned phone calls and unanswered text messages sent to Mayor Turner, Chief Acevedo and others. Travis had been as unsuccessful as his other councilmembers in getting replies from city officials, he said, when they requested information and resources. At a fraught City Council meeting two days later, on September 20, fellow councilman Mike Laster would echo his concerns, calling the city’s poor communication skills post-Harvey an “information blackout.”

So Travis had started taking matters into his own hands where he could. “We were intentionally flooded, and I’m running into resistance from my Mayor and his staff,” he said. District G, he pointed out, sat underwater for days longer than the rest of the city. "We got hit the hardest. We had the most houses flood. And I get that we have limited resources, but these other districts—they’re not like us."

Travis had relentlessly pushed for answers, asking about the potentially toxic sludge left behind by the floods (which hadn’t been tested by the city, despite his requests; later, a New York Times investigation would reveal the floodwaters in the Energy Corridor contained E. coli, “a measure of fecal contamination, at a level more than four times that considered safe”), residents’ complaints about a lack of police presence in devastated neighborhoods (the source of nearly half of his texts and calls from constituents), and the general scarcity of information.

“A lot of people think the inactivity of the city is me,” Travis said, shaking his head. “It’s not me. It’s the resistance I get. If you look at City Council, we have no power.”

When Houstonia spoke with the Mayor on October 11, he continued to strongly refute this assessment of the city’s response. “Police officers were serving as the gatekeepers in many of those streets, out there 24/7. The curfew was extended an extra week and a half just for the people in West Houston. Frankly, when the water did go down, the trucks, the contractors were in West Houston, and that area was clean within two to three weeks after the water went down.”

Though this was not entirely true—parts of Memorial were still covered with debris a month after the storm, during which time Houstonia visited the area nearly daily to document its cleanup—Turner reiterated his position: “I will push back very hard against anyone who claims that West Houston was ignored by the city. We expended a considerable amount of resources in terms of dollars and time and personnel.”

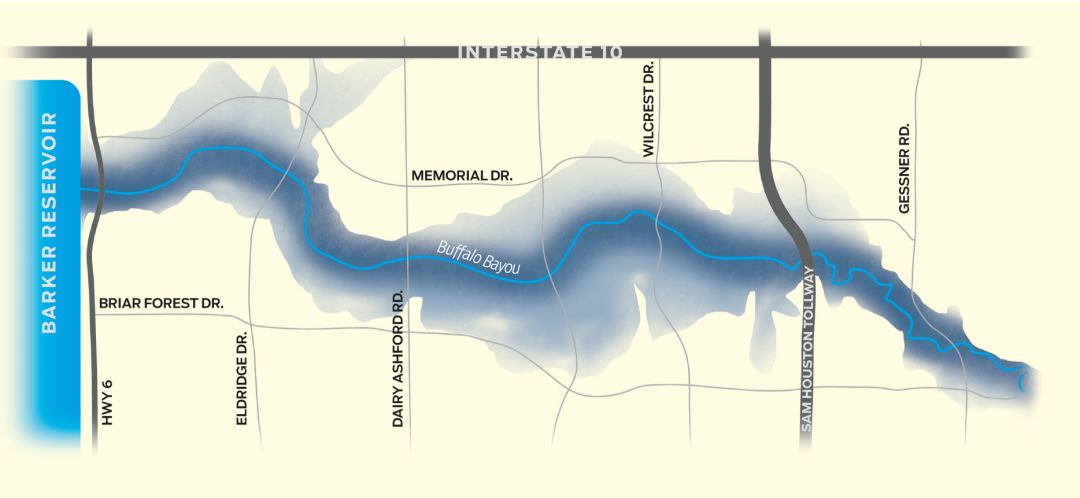

During the two weeks following the initial reservoir release on Aug. 28, Buffalo Bayou overflowed its banks most heavily from Highway 6 to Gessner Dr. (Not pictured: Addicks Reservoir)

On September 25, the Harris County Flood Control District finally held a long-awaited media briefing in the headquarters of TranStar. Requests for individual interviews with county officials had been denied, and so the press sat with bated breath as Harris County Judge Ed Emmett and Russ Poppe, the newest executive director of the Harris County Flood Control District, stepped behind the podium. They were joined by Harris County Engineer John Blount and newly beloved HCFCD Meteorologist Jeff Lindner, who seemed to have been trotted out as part of a good-will effort. Remember this guy, Houston? Y’all loved his updates so much during the storm you donated money to a vacation fund for him!

With the evaporation of much of that goodwill, public infighting at City Council meetings had picked up, along with a desire to hold someone, anyone, accountable, for both the citywide flooding and the decimation that occurred after the reservoir releases. Soon there was a deluge of questions from the pool of reporters: How far along was the buyout process? Was climate change now an accepted fact at the county or city levels? How many flooded homes would FEMA potentially purchase? Did we “cheap out” in maintaining our infrastructure over the years?

“Judge, are you any further along in the talk about a long-term solution in the sense of, are we going to get state or the feds to come on board? Is there going to be, like, a trillion-dollar bond package at some point to do all these … actual significant projects that might actually have an impact?” asked ABC-13’s Miya Shay.

“At this point, there’s lots of conversations, and we have to not let that conversation drift away,” Emmett responded. “We have to redefine … what is a 100-year flood? What’s a 500-year flood? I’ve said half-seriously over the last week or two, we’ve had three 500-year events in two years. Does that mean our definition of a 500-year event is wrong? Or does that mean we maybe have 1,500 years free and clear? I don’t think anybody thinks the latter is the case, so clearly we’ve got to go back and look at what our floodplains are and make adjustments.”

Bolstering infrastructure was just one of those adjustments. “We are going to have to look at spending serious amounts of money from the federal, state and local level in new reservoirs,” Emmett continued. “We need to complete all these [infrastructure] projects that Russ Poppe was talking about. We’ve got to do all the buyouts. And then we’ve gotta take a hard look at what are our rules and regulations relative to development, and are they good? And that’s all long-term. But I think that those things will happen. I don’t think there’s any question right now that everybody believes that flood control is the most important thing for our region.”

“How many homes were flooded from the reservoir releases from Addicks and Barker?” asked KHOU-11’s Shern-Min Chow.

“We’re working with the city on that information. We do know it’s probably several thousand,” Poppe said. “It’s a tough distinction to say how many homes flooded just from local rainfall versus the Corps releases.”

“For those homes, though, that didn’t flood during Harvey and flooded after the reservoir release, what we’re hearing from a lot of residents is that they just didn’t have any notice or any understanding of what the reservoir release meant,” Houstonia said. “So is there a plan in place for an alert system in the future, or better communication for the residents in those areas? They want to know why an evacuation wasn’t called for.”

“From the alert perspective, we do have the alert gage network that’s accessible on our website,” said Poppe. “It’s got 155 gages across the entire county, several of which were located along Buffalo Bayou. Those gages were active and were reporting during the entire Harvey event with the exception of one downtown.

“There were alerts given because our system was in place, and residents who’d signed up to receive those alerts were receiving them,” he continued, referring to the county’s Flood Warning System, housed on its own website; alerts are available via an RSS feed. “Obviously, I think we could expand our footprint to better push out that information; social media is a tool we’re looking at expanding our footprint into, to get announcements out that way.”

Finally, one last question was allowed as the press conference wrapped up: “Knowing that the reservoir releases of this magnitude were a contingency during catastrophic flooding, had there been previous studies done on what the downstream impact of something like that would look like?”

“The answer is yes,” said Poppe, “and the Corps has what they call a water-control manual, and they describe the various scenarios they could potentially see as the reservoirs would fill, and then what the resulting release rates would potentially have to be.”

“And those are public?”

“I’d have to check with the courts, but I’m certain that they are.” Later, Houstonia’s requests to see the manual, while not denied, were bounced around; as of press time, the Corps had not yet made it available.

If these studies were indeed publicly available at some point, why the confusion around how fast the waters would rise and whether or not the flooding would impact both roads and homes? Wouldn’t officials have known massive flooding was a huge risk for miles on either side of the bayou, and if so, shouldn’t they have ordered an evacuation at the same time the reservoirs were first released? Were the contents of these studies made available to city and county officials, to better plan for such a contingency?

The questions vied with those 8 million cubic feet of debris for the biggest mess left behind by Hurricane Harvey.

Barry LaCoste has decided to move forward with the expensive, extensive rebuilding process.

Image: Max Burkhalter

At the beginning of October, Barry LaCoste and his wife took Christopher away for the weekend, to stay with friends in Austin and visit one of their 2-year-old son’s favorite cartoons in real life: a giant steam train painted like Thomas the Tank Engine, which rumbles through Burnet on special occasions. But on the morning of Friday, October 6, it was back to the LaCostes’ new reality.

It had been a month since the flood waters receded in Memorial Thicket and the family was first able to reenter their home. In the meantime, they had decided that they weren’t ready to call it quits. This was their home, for better or worse, and they’d begun the long rebuilding process. But it was already fraught with complications.

“We’re making some progress, but it’s been a huge roller coaster,” LaCoste told us. Demolition was done; mold remediation and final drying-out of the house would come next. As for remodeling? “We’re still searching for contractors to take on the skilled tasks, but the good ones with references are too busy.”

It also had been difficult, LaCoste said, to acquire needed funding. “We received a FEMA grant to help get us started, but taking out a loan has been problematic.” So they were exploring options, including a high-interest home-improvement loan. “We were originally denied [a home disaster] loan through FEMA because our current mortgage made our debt-to-income ratio too high,” he said. “The officer is currently working on appealing that decision.”

In the midst of all this, LaCoste was still seeking answers of his own—and finding that those might be slower to come. On Tuesday, October 3, he’d attended a public town-hall meeting with the Army Corps of Engineers and state officials, including Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, at nearby St. John Vianney Catholic Church. “It was disappointing,” he said, “as the [Corps] couldn’t answer any burning questions due to the pending lawsuits.”

“I’m not an engineer, but I know we have to take some pressure off of the Addicks and Barker [reservoirs],” Patrick had told the concerned crowd gathered inside the church. And yet, Col. Paul Owen, the Southwestern Division Commander for the Corps, warned that another catastrophe could easily happen before any additional infrastructure projects were accomplished. “I think it’s important to understand the risk of where you’re living right now,” said Owen. “There’s no guarantee that [a] storm isn’t going to happen again.”

Still, LaCoste was optimistic. One day his home would be whole again, his son’s toys in a colorful jumble on the living room floor where they belong—not out on the lawn. And until then, he’d found a new sense of security in the community of friends, neighbors, coworkers, congregants and others who had rallied around West Houston families like his own.”

“Through their generosity we have a place to stay and cars to borrow,” Lacoste said. “We’ve received and continue to receive a lot of help from friends and family. I’m working on the house nearly every day, and I’m rarely alone.”