Erica Quinzel: Bat Woman

Image: Daniel Kramer

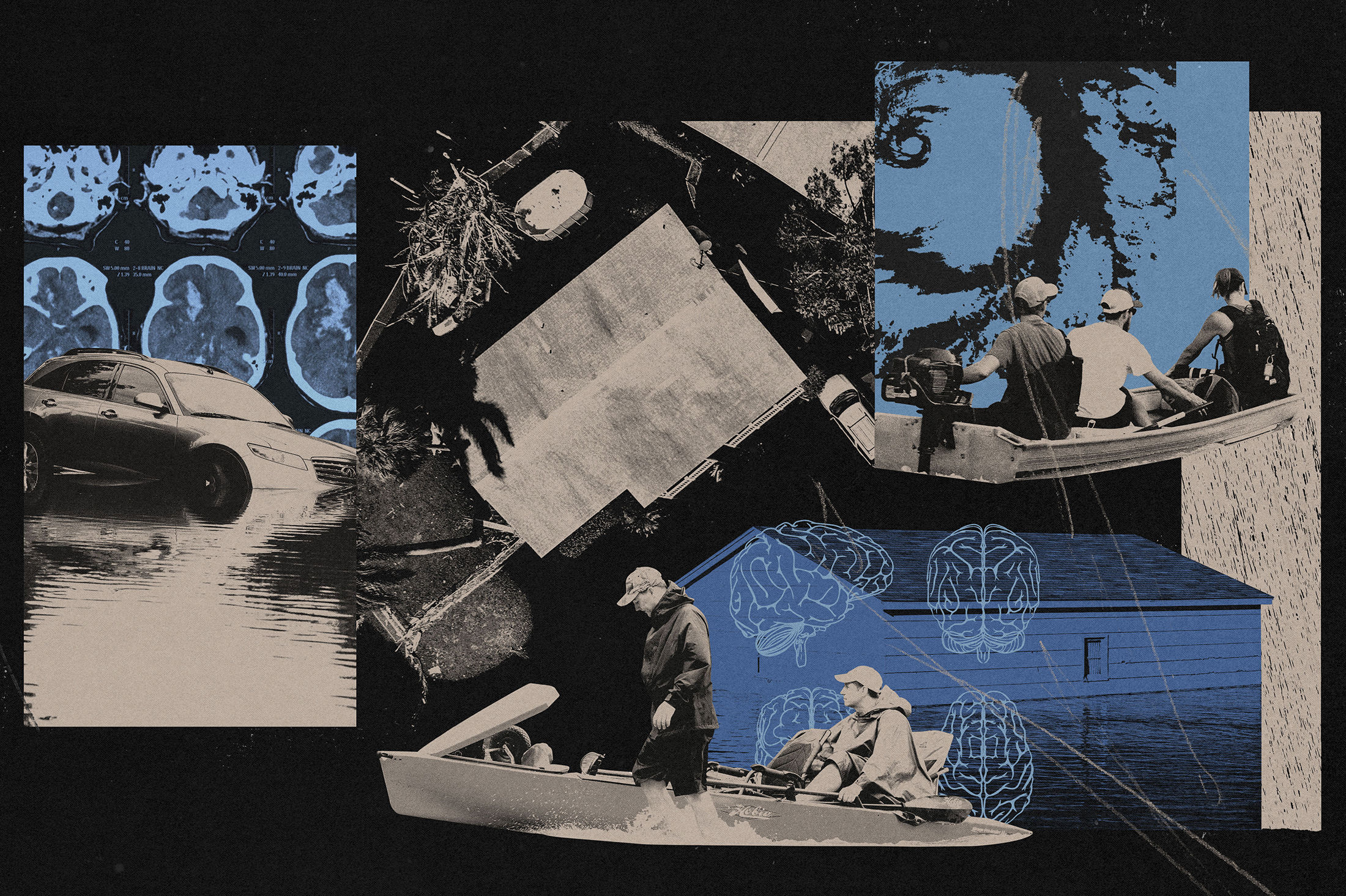

At the hottest part of a cloudless day, inside a dim, vacant parking structure overlooking Buffalo Bayou, Erica Quinzel’s worst fear came to pass.

“I’m inside the garage now,” she texted a Houstonia reporter that afternoon, the Friday after the storm. “They are all dead.”

The 29-year-old bat-care specialist had been battling for days to get back inside that garage, where, after the rain let up, a security guard had found her collecting bats either too wet or too weak to fly back to their colony. Quinzel explained that she was only there to rescue the animals, which would die without her help. The guard explained that he was going to call the police. “Literally, as he was kicking me out,” Quinzel said, “I’m grabbing and hooking bats to my shirt just to get them on me.”

She trespassed for a reason. Before Harvey, a famed colony of at least 250,000 Mexican free-tailed bats wedged themselves into the nooks and crannies of the Waugh Drive bridge that spans the bayou near the parking garage. But bats require a vertical drop to take flight, and by the time Harvey’s floodwaters swelled to meet the bridge, it was too late for many to escape.

Quinzel’s T-shirt announced her affiliation with Bat World Sanctuary, which is in Weatherford, half an hour west of Fort Worth. After innoculation against rabies and an apprenticeship, that’s where she’s spent mornings and evenings for the last five years, caring for animals for no salary, although onsite housing is provided.

One of Quinzel's beloved bats

Image: Morgan Kinney

Monday, when the worst of Harvey’s rain had passed, she and her Bat World team gathered some life vests, bought a boat, and headed toward a historic flooding event. Her day job—a store manager gig at mall staple Spencer’s—would have to wait.

After putting out a call on Bat World social media, Quinzel zipped about Montrose collecting displaced bats in mesh carriers before spending hours injecting the dehydrated bats with electrolytes and feeding them hydrolyzed protein, a hand-mixed slurry of ingredients to fill their sunken stomachs with nutrition. She hardly slept.

At sunset that Thursday, Quinzel crouched on the slope of the bayou, her black combat boots partially covering a large, photorealistic leg tattoo of a lesser longnose bat spreading its wings. The survivors of the Waugh Bridge colony were starting to emerge for the night, and her restored bats were about to rejoin the group. One by one, the palm-sized, wrinkled flying mammals emerged from the carriers, unfurled their wings, and flew off into the chirping mass.

The next day, when Quinzel finally got back into the parking garage and sent that text, she was dismayed as she surveyed the dehydrated, caved-in bat carcasses littering the six-level structure. She had, however, saved close to 400 bats, almost singlehandedly, not to mention a few squirrels and a bullfrog with a missing leg. Despite the casualties, two popped truck tires, and nothing but half a slice of cheese pizza in her stomach, she felt some satisfaction. “Even if I save just five bats,” she said, “that’s what I do.”