Meet the Four Texans Fighting for the Air We Breathe

If you were hogtied, blindfolded, thrown in a truck, and dumped on the side of the road somewhere in Houston, the first clue to your whereabouts would be your nostrils.

A musty cloud of diesel fumes could place you at the 290/610 interchange, or perhaps the nose-turning rotten egg stench—the “smell of money”—means you are in “Stinkadena.” The sickly-sweet smell of benzene, meanwhile, probably lands you near Manchester or Galena Park, or maybe La Porte. Whatever the odor, it’s a wayfinding tactic that relies on the fact that Houston stinks, always has.

Back in 1999, a USA Today headline conferred “gagging rights” on the Bayou City in an article snarkily headlined “Houston (cough) . . . we have a problem (cough).” Since then, largely due to ever-higher standards set by state and federal regulators to improve public health, that reputation has started to evaporate, sinking us from top billing to number 12 on the list of most polluted cities, just above Dallas.

But the agencies responsible for that progress in air quality have increasingly dubious records. For one, President Donald Trump–appointed EPA Administrator, Scott Pruitt, has sued the organization he now leads 14 times. He’s also yet to update his LinkedIn bio, in which he describes himself as a “leading advocate against the EPA’s activist agenda.”

Locally, there is a steady onslaught of concerning incidents. In Crosby, the Harvey-related explosion of the Arkema Chemical Plant is currently being litigated for the chemical manufacturer’s alleged negligence in failing to report and prevent illegal emissions. The ailing, 100-year-old Pasadena Refining Company has been sued at least twice in the last year for yet again violating its emissions permits, spewing tens of thousands of pounds of chemicals and particulate matter into the air over nearby communities. Then there’s the recent Texas Tribune analysis that found the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, the state equivalent of the EPA, only took punitive action against a small percentage of illegal polluters, choosing to instead let industry police itself.

Of course, there are examples of responsible government action, such as when Pruitt recently promised to clean up the San Jacinto Waste Pits, a local Superfund site—but only after hurricane flooding caused a rupture in the neglected project that leaked hazardous dioxin into the nearby river. This announcement ironically followed news about the potential closure of the Houston EPA lab responsible for testing samples from Superfund sites.

Concerned? You’re right to feel that way. Not long after President Trump was elected, Christopher Sellers, an environmental historian at Stony Brook University, gathered colleagues to interview current and former EPA staffers throughout the early days of the transition. In a 97-page report titled “The EPA Under Siege,” released last summer, they paint a bleak picture for the nation’s chief environmental regulator, detailing sweetheart deals with industry and goals to cut agency staff by two-thirds.

“To get rid of the agency… That’s a little bit of a conservative pipe dream,” Sellers tells us. “The more likely scenario is that they’ll make it a shell of what it was. It’ll be there still in name, but it won’t be able to do very much.”

If the government seems unlikely to do something about our air quality, who will? Short answer: the rest of us. Houstonia focused on four different ways private citizens are waging war for the air they breathe along our stretch of the Gulf Coast. We talked to a Baytown-born retiree who decided to sue Exxon, an Austin software engineer using public data to help track illegal pollution throughout Texas, a charismatic political organizer fighting apathy in Port Arthur, and a filmmaker channeling artists’ abilities to convey what life in Gulf Coast refinery towns is actually like. (And if you think artwork can’t improve air quality, he’s here to tell you to think again.)

Some of the local citizens in the following pages call themselves activists; some say they’re simply doing the right thing. But regardless of motivation, there are things to be done beyond sorting your recyclables or casting a hopeful vote. Really, these folks just did something. So can you.

Sharon Sprayberry knew something was amiss at ExxonMobil's Baytown complex.

Image: Anthony Guana

Sharon Sprayberry, the Baytown retiree who helped take Exxon to court

At around 8 p.m. on a summer evening in 2006, Sharon Sprayberry witnessed a yellow-gold glow descend upon Baytown, along with a steady roar like a freight train hurtling toward her single-story home. She recognized the markers of a tornado, but as the night sky remained bright even while the sun set and the roar continued, the Baytown native’s mind jumped to the sprawling, 3,400-acre ExxonMobil industrial complex about a mile to the west. Rushing outside to look in that direction, she saw several massive, candle-like flares firing into the night.

Flares are normal, but nothing about this evening seemed routine, that unignorable sound a sign of immense pressure being released by some of the largest flares Sprayberry had ever witnessed. Fearing an explosion, she hunkered down, shut off the A/C to preempt whatever fumes she assumed were wafting over the city, and remained awake to monitor the uncanny not-dark outside. She waited to hear something on the news, or from Exxon. She never did.

The roar subsided by 3 or 4 a.m., and she emerged at daybreak from her now-sweltering home. “My neighbors were just going on the next day like nothing had happened,” she recalls. “I said, ‘Did you hear this boom?’ They said, ‘Oh, it’s nothing.’ It didn’t seem to bother them, which told me they must be accustomed to this, which I believe to this day that they are. But it was unsettling to me.”

When the freight-train roar came again and again, Sprayberry began making fruitless calls to an Exxon hotline, which assured her nothing was amiss. Then she dialed the EPA’s regional office to try and tell them about the boom and the flares and the concerning rotten-egg smell familiar to anyone who’s driven down the elevated Spur 330, past the sprawling ExxonMobil complex almost three times the size of downtown Houston, and into the city. Eventually, the EPA bounced her over to the TCEQ, the state regulator that oversees self-reported emissions. The canned response felt like a dead end.

Fed up with the lack of action, Sprayberry went online to research the federal Clean Air Act, discovering Section 304, which outlines something called citizen suits. These are the equivalent of asking for the manager: If the EPA and other regulators fail to penalize illegal polluters, Section 304 permits citizens to step in for those agencies and bring down the regulatory hammer themselves in court. It was exactly what she was looking for: “I wanted to do something. I wanted people to listen to me. I wanted to say this is not right, you can’t do this!”

Eventually, more search queries led Sprayberry to Environment Texas, an Austin-based advocacy group that makes a job of filing these suits, among other matters, and she shot off a message. “It was sort of an email putting them on notice,” she recalls. “What are you doing to help me down here in Baytown?”

To her surprise, Luke Metzger, director of Environment Texas, replied that his organization was doing something to help, that they were in the early stages of preparing a citizen suit against that same Exxon Baytown facility. If she wanted to get involved, he could put her in touch with the legal team.

Sprayberry hesitated. After all, her father had worked at the Exxon refinery for 40 years. Still, she’d noticed an unmistakable change when she moved back to Baytown in 2004, after a long absence, to take a job in educational technology: Exxon’s presence, in particular, had exploded, and she saw the flares, smelled the fumes, and struggled with worsening asthma that felt like “breathing through a straw that just keeps getting more and more narrow.” She knew what she had to do.

Environment Texas filed a citizen suit on behalf of Sprayberry and several other Baytown citizens, with support from the Sierra Club, in December 2010. The initial complaint fingered Exxon for illegally releasing more than 8 million pounds of unpermitted pollution since 2005. That total included a list of nasty, volatile organic compounds that serve as the ingredients for lung-shredding ozone, including benzene, a sweet-smelling gas connected to increased risk of blood cancer, and hydrogen sulfide, the rotten-egg-smelling gas known, even in small amounts, to cause death.

After all the years building to that moment—and after a nerve-wracking deposition with Exxon’s lawyers—Sprayberry was brought to the stand for less than an hour in 2014, when the 13-day bench trial finally commenced. Her lawyers furnished a pep talk and a drink of water, she answered questions from the judge, and she was cross-examined. Then Sprayberry went home. “I remember as I drove out,” she says, “I was just really happy that I could put it in the rear-view mirror—literally—because there had been such a long period of time getting to that point.”

By then, Sprayberry had left Baytown for good. She’d retired early, at age 60, and grown fed up with the quality of life near Exxon, where the elevated risk of developing cancer is well-documented. She’s been living in McGregor, a suburb of Waco, since 2012, enjoying the slower pace and fresh air. That straw in her chest is mostly gone.

Today, climate change is a big issue for her, and she’s marched in Austin. “Much to their chagrin, my friends call me the environmental nutcase,” Sprayberry says. “I don’t think they like my Facebook posts.” Still, a decade later, she’s frustrated she has to do this work at all. “The Clean Air Act had been in place for a while,” she says, “and why did I have to get involved? Why didn’t the Environmental Protection Agency do its job? Or TCEQ? Or any agency that had the oversight there?”

Ask Charles Irvine, a Houston-based environmental lawyer, and the answer is simple: They didn’t do their job.

“Into each of these environmental statutes, [lawmakers] wrote these citizen suits as sort of a safety valve,” he says. “At any point during the Exxon lawsuit, EPA or the State of Texas could have come in and said We’re taking over now: Citizens, stand back, we’re here to save the day! They could have come in and crafted a settlement or litigated it. The citizen only gets to bring the enforcement action when there is an absence of governmental enforcement.”

In April 2017, after the initial pro-Exxon judgment was remanded, the conservative-leaning Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the citizens and issued the oil and gas giant a $19.95 million penalty, thought to be the largest ever for a suit of its kind. But no checks have been written yet; Exxon appealed the decision in late August.

No matter, says Sprayberry. Even if Exxon never coughs up a cent—of course, she hopes they will—she’s made her point. “There’s times in everyone’s life where you have to stand up,” she says. “You have to stand up for what you believe—whether you’re going to win or not. It’s important to say it and to demonstrate it, because it may make a difference for somebody else.”

Software engineer Kevin Wood helps analyze and track air pollution across Texas.

Image: Robert Gomez

Kevin Wood, the Austin software engineer harnessing Texas emissions records for the public good

After 13 years working on classroom technologies for UT Austin and Purdue, Kevin Wood decided to call it quits. This was a good move, he says. “It turns out, the private sector actually pays people money.”

For Wood, going private meant startups, among them Map My Fitness, a workout app eventually purchased by Under Armour. But although he was making money, the work wasn’t fulfilling. So Wood took a year off to find himself, finally deciding that he wanted to help those working to help others. He’d done some mentoring in the past, as well as working a crisis and suicide hotline. It always felt good to have an impact.

So, on a whim in 2015, he reached out to Environment Texas to offer his skills as a software engineer. He liked how they weren’t afraid to go beyond “raising awareness” to file lawsuits. Even so, he didn’t know how they might put him to use. “I honestly thought the response back would be to hand out flyers, I had no idea.”

Instead, he was presented with an early prototype of what would become Neighborhood Witness. Developed in concert with Air Alliance Houston, the Environmental Integrity Project, Public Citizen Texas and others, the idea for the service was to make public data useful to the average person. Wood soon took the lead on the project.

For years, citizens have been able to access Texas petrochemical facilities’ self-reported emissions via an online database, but it’s been on them to decipher the labyrinth of nested tables and technical language. Neighborhood Witness simplifies it all. Users type in their email and ZIP code to receive automatic email notifications whenever a nearby facility pollutes beyond its permits. In that notification, there is a template to file an official complaint with TCEQ, which is required to investigate every complaint filed. Additionally, the Neighborhood Witness website houses a searchable database where you can find exactly who emitted what, and from where it was emitted.

The tool confirms what many already suspected—both citizens like Sprayberry in Baytown and residents of places like Manchester, the community on Houston’s east side that regularly suffers odors emanating from the nearby Ship Channel and refineries. During Hurricane Harvey, a terrible “mystery stench” lingered over the area for days; a quick search on Neighborhood Witness provides records on how the nearby Valero facility emitted thousands of pounds of hazardous chemicals on August 27, in the throes of the storm. While there is a lag time between the emission event and when it appears in the database, it allows Houstonians to shore up suspicion with records.

“If you’re used to smelling pollution all the time, you don’t know when the company breaks the law,” says Luke Metzger, the director of Environment Texas. “They have plenty of legal pollution you smell and breathe all the time. Neighborhood Witness helps you say, ‘This is different, this time they actually broke the law, and what you’re smelling is illegal, and you should speak out.’”

The tool also facilitates analysis of that self-reported public data to determine pollution hotspots and nail down repeat offenders.

“We got to see something like 300 specific chemicals released across Texas on an almost daily basis,” Wood says. “There was some confirmation of belief. The hotspots were where [Environment Texas] thought they were, but we got to see them. The initial pitch was, get the community involved, get the community filing reports. As we got going, I came to understand that this is going to drive some of those lawsuits, and where some of the activism is focused.”

As of now, the tool remains limited to email notifications and the searchable database, but Wood is brimming with ideas. He says the last brainstorming session yielded more than four pages of features to add, including a section that will educate citizens on the potential impacts of these pollutants—for example, that benzene is a known carcinogen. They might create an app to deliver push notifications to your smartphone, or include a feature for individuals to upload photos and videos of potential violations. Exactly which ideas make the cut remains to be seen, especially since Wood only devotes about five hours per week to the project. Even now, he thinks of himself only as a normal volunteer.

“I like supporting people who are passionate about a topic,” Wood says. “I am not an activist; I am an engineer that activists can point toward a goal.”

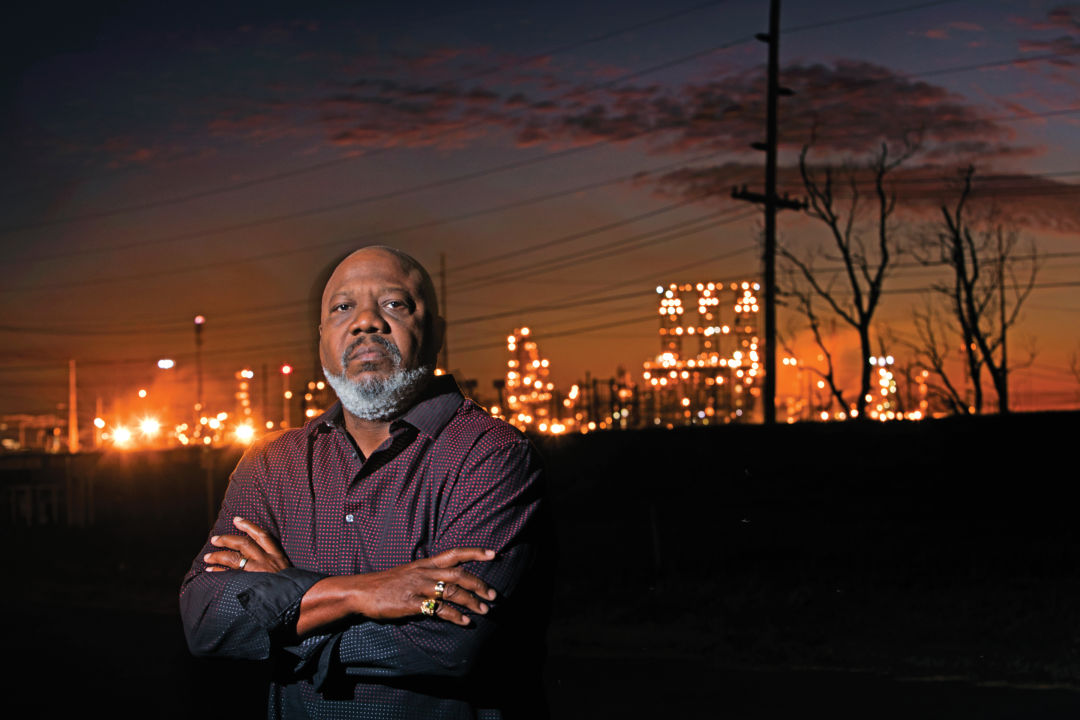

Hilton Kelley wants Port Arthur to stand up for itself.

Image: Daniel Kramer

Hilton Kelley, the Port Arthur actor-turned-activist who believes in the power of the people

Three months after Harvey, Hilton Kelley was living out of a Red Roof Inn in Beaumont while tearing out the subfloor of his flooded Port Arthur home. Amid all that activity, he also found the time to fly to Las Vegas for a meeting he believed could change the future of his city.

“We’re about to create a whole new workforce,” he tells us.

Vipeq Industries, the company he met with, manufactures a spray-on building material from recycled cork trees that insulates, protects against mildew, and possesses fire-retardant properties. The product would bring jobs to Port Arthur, and Kelley secured a meeting between Vipeq, city council and investors to cement its presence in the area.

Kelley is not a businessman, though. Instead, he’s pursuing the deal under the guise of the Port Arthur organization where he’s founder and director, Community In-Power and Development Association (CIDA), which works to empower the town’s citizens with both economic opportunity and the tools to stand up to illegal pollution. Port Arthur is surrounded by a cadre of petrochemical complexes, including the Saudi-owned Motiva refinery—the largest in North America.

CIDA helps to prepare folks for jobs in carpentry, plumbing, concrete and other fields that are not the oil and gas industry. That industry, of course, dominates the Golden Triangle area of Beaumont, Orange, and Port Arthur, where the per capita income remains significantly lower—and rates of cancer and asthma significantly higher—than the rest of Texas.

The 57-year-old founded CIDA in 2000, the year he abandoned his prospects as an actor. At the time, he was working on Nash Bridges, the police drama starring Don Johnson and Cheech Marin, but an eye-opening visit home to his native Port Arthur for Mardi Gras pushed him to return and to help mobilize his community.

When he wants to get something done, Kelley isn’t averse to shock tactics. In 2004, he famously dragged a coffin with a smokestack painted on it to the steps of Port Arthur’s city hall to get the attention of the mayor. Later, he traveled to Europe to sound off at Shell’s annual shareholder meeting, giving an earful to the company’s then-chairman—all while wearing a cowboy hat. This is the kind of work that won him the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2011, widely regarded as the “Green Nobel.”

More recently, after Harvey, when dozens of citizens were evicted from their apartments with nowhere to go, Kelley put out a call via Facebook, rounded up women and small children, and personally marched them to speak with Port Arthur’s mayor and city manager, breaking those officials’ silence and insisting they provide temporary shelter, which they did. And when the city began dumping hurricane debris directly across from residential housing, Kelley organized a human barricade that blocked the trucks in the street. The city closed the site, although it says the pile was safe and properly permitted.

The initial response to Kelley’s efforts through CIDA was always a variation on, “Well, what can we do?” Many held the belief that one must be a full-time activist with all the attendant skills to effect change. (“Nothing could be further from the truth,” he says.) The job, Kelley says, is to make people realize how justice and political action does not come from George Soros–funded mobs, but from regular people deciding a cause is important to them. You don’t have to quit your job or have a degree or “know the right people” to get started. Kelley presents it as a simple choice between complacency and results.

“I’ve had people tell me, ‘I’m not into politics, I don’t get into politics,’” he says. “Well, whether you want to be into politics or not, politics impacts your life. So either you’re going to get into politics and help fight for your rights, or you’re going to sit on the sideline and just complain. This is the kind of conversation I engage them in: ‘Which one do you want to do? I can’t continue to fight for you independently, alone. I need you standing with me to help me bring reprieve to your issues.’”

In late October, Kelley announced his intention to run for mayor in 2019. Still, he maintains, his city doesn’t need him to be its leader; it needs its citizens to speak up.

“If they put me there, I’ll serve,” says Kelley. “But what I’m also trying to educate them on is that to help you bring reprieve to your issues to this city, I don’t have to be your mayor. I could just teach you to get things done in your city, but you have to participate.”

John Fiege documents artists to capture hope for Gulf Coast industrial communities.

Image: Robert Gomez

John Fiege, a filmmaker whose artistic documentary paints a different picture of air quality along the Gulf Coast

Ebony Stewart turns her head from looking out the window onto Baytown, stares into the camera, and begins to recite a spoken-word account of life in her hometown:

“The City of Baytown is made of old money, lower- to middle-class families, and pollution,” she intones, “but if you get a job at a chemical plant, you don’t have time to think of a solution. I guess my brother, my uncle and my cousins are sellouts cause they went industrial instead of the drug route.”

It was in 2016 that Austin-based filmmaker John Fiege approached Stewart about participating in his documentary In the Air, still in production, on environmental-justice issues in Stewart’s native Baytown and elsewhere along the Gulf Coast. Baytown, half an hour east of Houston, is a prime example of an unfortunate reality: Places with the worst pollution are primarily inhabited by those who are either economically disadvantaged, non-white, or both. It’s no coincidence that Baytown, which is surrounded by petrochemical facilities, is primarily inhabited by people of color, or that its rate of poverty is significantly higher than the national average.

At first, Stewart hadn’t put all the pieces together, connecting the all-too-familiar cancer, smells, and lack of upward mobility. “This is not normal,” she remembers Fiege saying. Soon, she reexamined the place where she grew up, and where much of her family still lives.

“You don’t look at it like everyone else looks at it when they come there, because you’ve been living and surviving that way for so long,” she tells us. “I hate that my eyes are watery, I hate that I have these allergies. But you don’t describe it like that, ‘environmental injustice.’ That’s not a word I would toss around with my family at dinner.”

Stewart, along with a band of fellow poets, artists, and dancers, agreed to team up with Fiege to create In the Air, which is slated for a 2019 premiere, and which will convey the reality of life in industrial communities all along the Gulf Coast through a variety of performances.

The film will not rely on narration or interviews. Instead, the artists use their craft to speak to their experience in these polluted places. It’s a departure from the filmmaker’s previous project Above All Else (2014), a more traditional documentary that follows a Texas man determined to stop the Keystone XL pipeline—who, of course, failed. After that project, Fiege says, he needed a break from telling depressing stories. In the Air is his attempt to use art to find a positive lens through which to examine the human cost of the petrochemical industry.

“We’re not avoiding anything because it’s too depressing,” says Fiege. “But if we can communicate those stories and those ideas through something that’s beautiful in some way, that’s exciting culturally, my hope is that we’re going to reach new audiences, broader audiences.”

Ebony Stewart uses spoken word to process the environmental injustices of her native Baytown.

Image: Daniel Kramer

He might be onto something, says Adam Rome, an environmental historian and film adviser, who believes realizations like the one Stewart had are an important first step in awakening people to issues that affect them. It’s a good thing, he says, that In the Air chronicles how people actually struggle to exist in these places instead of harping on a plant belching who-knows-what into the air. The important story is how humans relate to nature. “You can deal in the short term with some small pollution problems, but to truly have a different relationship with the non-human world requires reimagining our place in the world,” he says. “Reimagining is a realm that art can play a role in. … That ultimately will change the world.”

A theme of the movie is people using the skills that they have to bring about change. In other words, if you’re good at art, do that. Fiege says he’s not likely to lead a protest—he makes films. And Stewart combines spoken word with her authentic experience to convey the complexity and the beauty of the issues facing her hometown. “Especially black and brown communities, what do we know besides making it work?” asks Stewart, who now lives on Houston’s north side. “I just wanted to capture those moments where this ugly is so beautiful that it’s untenable.”

Another featured artist, Houston-based choreographer Walter Hull, explores the physical impacts of environmental injustice through an original dance that conjures the nostril-curling smell of sulfur and almost ubiquitous asthma of his native Lake Charles, Louisiana, another Gulf Coast refinery town. Scenes from the trailer show young dancers wearing surgical masks and latex gloves, and twisting between lines of strung-up caution tape.

The inspiration came to Hull after he read Between the World and Me, in which journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates chronicles how to this day, being black in America means someone else maintaining control over your body. “I thought about that,” says Hull. “Sometimes people have to live in certain communities because it’s what they can afford, or it’s what they know. But your body is not protected in this community through the air. That’s crazy. That’s where I got that idea of really putting the focus on the body with the movement and the camera shots.”

When he finishes the documentary, outside screenings at festivals and theaters, Fiege hopes to deploy it as an educational tool in the same communities where he’s filming. He wants the artists to be present to work with the kids and to help them process their world through the same creative lens. In the Air could very well be the first step that will spur individuals to act in real, political ways—ways even more important, Fiege says, under the current administration.

“When whole communities, whole churches, whole political parties reject things as basic as science and facts, how do you contend with that?” asks Fiege. “My answer to that is, you organize the people who are paying attention, and you get them more engaged in the political process and connecting them with other communities.”