Houston Architecture, from A to Z

What’s Houston’s architectural style? Some would say we don’t have one. That isn’t true, exactly, but it is quite hard to define. Which is why we decided to use every letter of the alphabet to describe what our city looks like. Put it all together, and a picture emerges, of a diverse and fascinating city.

The Clarke & Courts building, now home to TriBeca Lofts

Image: CC/Wikimedia/Jujutacular

A is for Art Deco

From shopping centers to diners to City Hall, elements of original art deco are on full display all around the metropolis. Want to take a tour? Hit the Tower Theater (now El Real Tex-Mex Café), the Alabama Theatre (now Trader Joe’s), the 1926 Gulf Filling Station in Midtown (now Retrospect Coffee Bar), Albritton’s Eats (now Panadería La Reynera), Clarke & Courts Printing & Lithography (now TriBeca Lofts), Transco Tower (now Williams Tower), and the River Oaks Theatre and Shopping Center (hey, still the River Oaks Theatre and Shopping Center!).

Bungalows, like this one on Harvard St., abound in the Heights.

Image: cc/wikimedia/Ed Uthman

B is for Bungalows

Craftsman bungalows were the rage in Houston, particularly the Heights, between 1905 and 1925, offering plenty of windows and, of course, those iconic front porches, which served as the original A/C systems back in the day. Today these cozy homes are all the rage once more, and they go for a premium—in the Heights, somewhere between $300 and $500 a square foot. Many homeowners are doubling or, in some cases, tripling their bungalows’ size with sleuth rear additions and partial second stories, maintaining their charm without sacrificing modern-day comforts.

A rendering of a shipping-container project by Kinetic Design Lab

Image: Courtesy of Devin Robinson

C is for Containers

“I’ve seen shipping containers come up and down the port my entire life,” says native Houstonian Devin Robinson, architectural designer and founding principal of Kinetic Design Lab. “They always fascinated me as these sort of Lego blocks.” He saw them stacked up on 610, too. And he’d wonder: Why are people not using these as building elements, and they’re just collecting dust? Could people live in them? Yup! They can be carved, cured, molded, and bent, made into transportable homes and businesses, which is exactly what Robinson now does. They’re often colorful, imbued with cultural influences from their world travels, and he likes to maintain those qualities in his design. “There’s some sort of sexiness to them,” he says, “that resonates with people.”

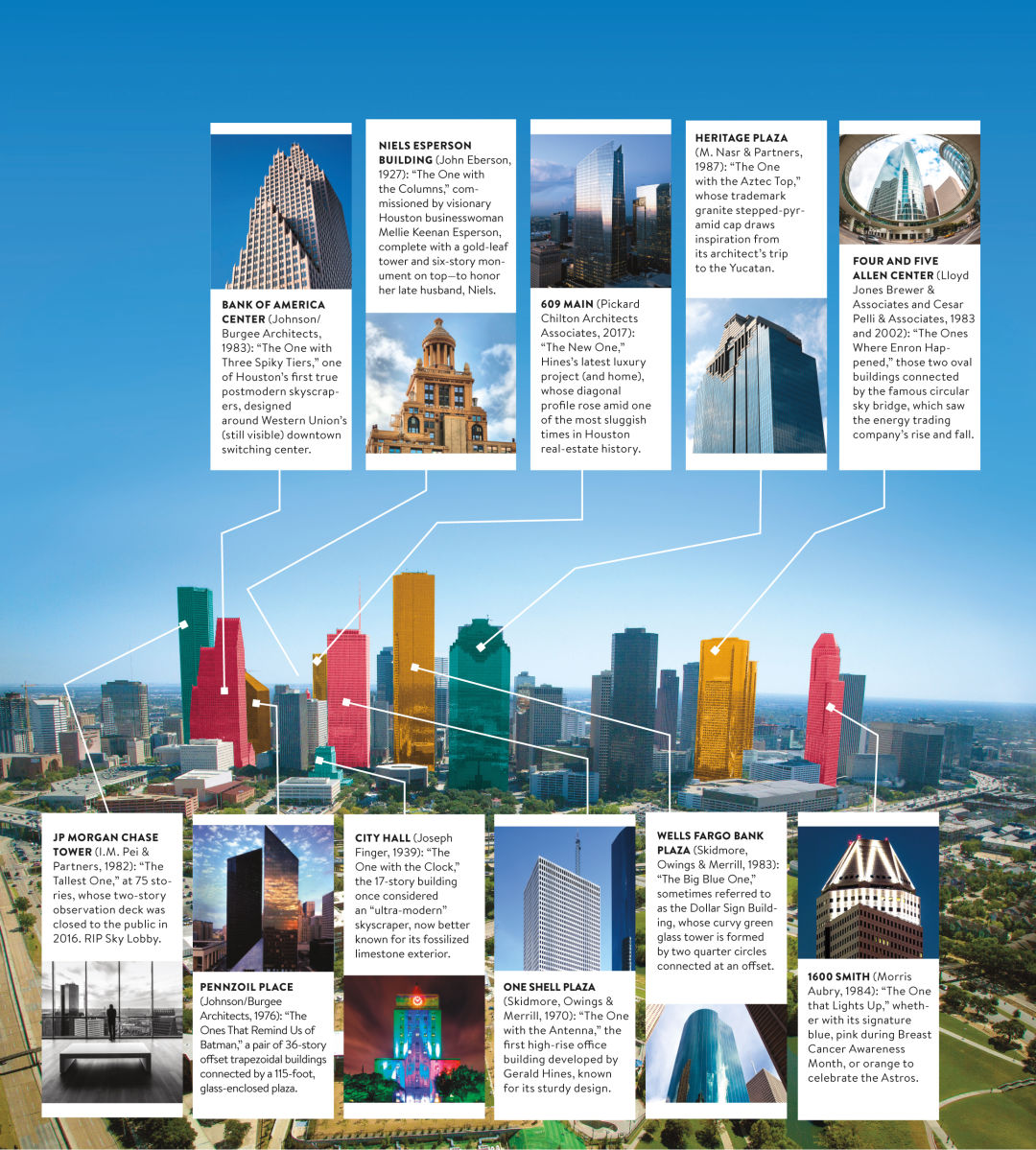

D is for Downtown Skyline

Too many Houstonians can’t name their downtown buildings. We’re here to help with this cheat sheet:

Image: Visit Houston

E is for EaDo's Revival

When Jake Donaldson moved his company’s headquarters to EaDo in 2016, he took precautions to keep his employees safe. “When we first moved in, it was a little unnerving,” he recalls. But over the past few years, thanks in large part to spaces he and his team at Method Architecture have created—8th Wonder Brewery, Chapman & Kirby—the gritty neighborhood has transformed itself. Old industrial buildings now serve as funky bars and eclectic music venues; bay doors, corrugated metal, concrete floors, and large steel windows remain, but with entirely new purposes. The hope is for EaDo to see mid-rise and high-rise towers come in, along with more retail, while remaining recognizable, with architects and developers continuing the trend Method started. “You have to leave some of the existing buildings and flavor of the surrounding area,” Donaldson says. “You can’t just wipe everything clean.”

F is for Flood-Proofing

Houston architects and planners are now conceptualizing ways to build not just around water, but above it and through it. These are the major ways they’re rethinking design in a post-Harvey era, per Peter Merwin, principal at Gensler:

Build high and dry.

As of September 1, city regulations now call for all new construction to be built above the 500-year flood plain, plus an additional two feet. “It’s kind of a big deal,” Merwin says. “I haven’t heard people completely freaking out about it yet, but it’s going to have costs and logistical issues in all properties.” Still: “It’s put in place for all the right reasons. We don’t want to have a repeat of what’s happened.”

Build to rebuild.

“We can build things in an impermanent way,” Merwin says. For example, some architects and builders now plan to install sheetrock walls—which can act like giant sponges, absorbing water and moisture—in horizontal strips instead of vertical ones, so that smaller pieces can be removed, saving time and money.

Think rock bottom.

“We may need to take a different attitude about the lower level of a building,” Merwin explains. Not only should residents move valuables and main living areas to upper levels when possible, but designers should select smart materials that allow for the inevitable presence of water in our community. “If you build in a concrete block structure, no harm, no foul. It gets wet, and it dries, and we are good to go.”

G is for Giant

The numbers speak for themselves...

Image: Shutterstock

2.4 million

Square feet occupied by Houston’s Galleria, home to 400 stores and restaurants, 2 hotels, 3 business towers, and 13,000 parking spaces.

Image: Library of Congress

1 million

Square feet of space at the historic Astrodome. The recently launched $105 million revitalization plan for “The Eighth Wonder of the World,” which will create 9 acres of open space for conventions and other endeavors, should be complete in 2020.

Image: Shutterstock

1.8 million

Square feet inside the George R. Brown Convention Center, which combines 3 massive, double-volume convention halls, a third-level meeting and exhibition space, and various promenades and parking spaces.

Image: Sothebyshomes.com

26,401

Square feet of space at Chateau Carnarvon, Houston’s most expensive residential listing ever, listed for $43 million in 2014. With no takers, the price for the 8-bedroom, 7-bath home was reduced to just under $30 million—still a record high—in May.

Image: Amy Kinkead

H is for Hines, Gerald

In Houston, Hines’s name is better known than any architect’s. Now 93, the real estate developer—who started out in a one-man office on Anita Street—is worth an estimated $1.3 billion, with his firm boasting more than 1,300 properties in 24 countries.

Hines’s legend took root in the ’60s with the completion of One Shell Plaza, the 50-story headquarters for Shell Oil Co. that was his first contribution to the downtown skyline. He went on to myriad high-profile collaborations, introducing Houston to nationally known architects such as I.M. Pei, Philip Johnson, and Frank Gehry. “He was one of the first developers to demonstrate that the building could be more valuable because of the architecture,” says Kevin Batchelor, senior managing director for Hines’s southwest region and an architect himself. “His buildings express architecture with a capital A.”

Hines’s huge Houston projects include The Galleria (“A shopping center it is not,” he said in 1970. “It will be a new downtown.”), Pennzoil Place, and JP Morgan Chase Tower. “I’ve heard, ‘Houston’s this incredible place where they do incredible things,’” says Batchelor, who came here to work for Hines after stints in New York and Paris. “It’s still a place where you can make that happen. You have great men like Gerry Hines who did it, and inspire others to keep doing it.”

Life off I-45: an apartment with a view, indeed.

I is for Interstate Views

Checking in on traffic is a constant in Houston, and some are willing to pay a premium to do so from their living rooms. Lofts overlooking that ghastly I-10 curve, penthouse suites with views of the state’s most congested stretch of interstate (610 near the Galleria), and balconies that we’re sure a car on the Pierce Elevated is going to slam into one day—we’ve seen it all in Houston.

J is for Juxtaposition

For more on why this could only happen in Houston, see “Z is for zoning.”

K is for Kirby Drive Mansions

Developed as Houston’s first master-planned community in the mid-’20s, the meticulously mapped, 1,100-acre neighborhood known as River Oaks is home to the city’s most opulent estates—and elite residents. Its most public-facing street, Kirby Drive, exhibits the range of architectural styles found in the prestigious zip code. See:

Image: Amy Kinkead

Tudor Revival

929 Kirby, built in 1929 and valued at $2.1 million, formerly home to famed defense attorney Richard “Racehorse” Haynes.

Image: Amy Kinkead

Contemporary

1000 Kirby, built in 1986 and valued at $20 million, originally owned by Saudi Prince Abdulrahman bin Faisal.

Image: Amy Kinkead

Southern Colonial

1059 Kirby, built in 1928 and valued at $3.1 million, an original spec home in the neighborhood, where former Houston mayor Roy “The Judge” Hofheinz once resided.

Image: Amy Kinkead

English Manorial

1419 Kirby, built in 1931 and valued at $3.8 million, by glass ceiling-buster Katharine Mott, who, with her husband Larry, designed multiple other homes in the area.

Image: Amy Kinkead

Neoclassical

1561 Kirby, built in 1935 and valued at $2.9 million, where, in 1969, prominent plastic surgeon John Robert Hill is suspected to have fatally poisoned his wife, socialite Joan Robinson.

Image: CC/Wikimedia

L is for Lakewood Church

Houston is home to the country’s biggest megachurch, so it follows that Joel Osteen’s Lakewood, which averages more than 50,000 weekly attendees, requires a venue as colossal as its congregation: the former Summit/Compaq Center on the Southwest Freeway, which for decades hosted Rockets games and huge concerts. In 2003, after Toyota Center took over as the city’s arena of choice, Lakewood leased the building from the city, investing nearly $100 million in renovations before buying it outright in 2010 for a reported $7.5 million; today the church seats more than 16,000 and includes a bookstore, a coffee shop, and indoor waterfalls. And it’s not the only megachurch in town, either: Second Baptist, New Life Church, The Fountain of Praise, Temple Regional de la Luz del Mundo, and Christ the Redeemer Catholic Church all have massive structures, too, with congregations to match.

Consistency: in short supply in the city, everywhere in the 'burbs.

M is for Master-Planned Communities

If central Houston is the rainbow sherbet of the local architecture landscape, the surrounding suburbs are vanilla, built around plans and rules, and lots of them. Escape the Beltway, and you’ll find most of Houston’s 100-plus master-planned communities taking suburban to the next level with homes, community spaces, amenities, schools, businesses, and hotels that, in many ways, function as their own self-contained cities. Architectural styles vary but are consistent throughout each. McMansions, of course, abound, and they sell: Greater Houston was home to 10 of the 50 bestselling master-planned communities in the entire country last year, the most of any major metro.

Zui Ng's Shotgun Chameleon

Image: ZDES

N is for Ng, Zui

Shotgun houses are said to have arrived in New Orleans by way of Haiti before taking root in Houston’s black community in the 1880s. A decade ago, inspired by these structures, local architect/Prairie View A&M professor Zui Ng conceived of “Shotgun Chameleon,” the 1,500-square-foot structure where he and his family now live, made with sustainable materials and designed to subdivide and adapt to the owner’s needs over time.

The design includes a ground-floor unit that can be rented out to cover the home’s mortgage, Ng says, an important consideration in his economically driven urban projects. In his work he aims to prove that, with some forward thinking, “you can actually live free.”

Ng’s plan won an international competition that sought replacement designs for homes destroyed by Hurricane Katrina; today it’s exhibited at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. Among other innovative projects, Ng’s currently working on a “Quarter House” that will take Shotgun Chameleon “one step further,” he says, splitting into four 500-square-foot spaces, in a model aimed at students.

Image: Shutterstock

O is for Outer Space

When humans colonize the moon—which, according to some NASA scientists, could happen as soon as 2022—there’s a good chance they’ll be living in houses designed by UH alums. The university is home to the world’s only space-architecture school: the Sasakawa International Center for Space Architecture, founded in 1987. This interdisciplinary master’s program, which melds design, engineering, and physics to conceptualize habitats for extreme environments, attracts students from all over the world. “A building is not just a shell, it’s not just floors, it’s a system of systems,” says SICSA director Olga Bannova. “When you design for space, it’s even more critical to understand how the systems work and how people will fit in it. Everything is critical. There is no such thing as, ‘well, that will be okay.’ If there’s no air, there’s no life.”

P is for Pools

9,472

Homes with pools sold in Houston in 2017

4,001

New residential pool permits issued in 2017

78

Percentage of Houston apartments with a pool (compared to 20 percent nationwide)

37

Public pools operated by the city

1

40-stories-high, glass-bottomed “sky pool,” pictured here, at Market Square Tower

Image: Concierge Auctions

Q is for Quirky

In Houston, just about anything goes. And we do mean anything. Like: brewskis as construction material (Beer Can House, 222 Malone St.), a mini White House on the bay (Gov. Ross Sterling Mansion, 515 Bayridge Rd.), a 72-foot statue of Guanyin, the East Asian goddess of compassion (Vietnamese Buddhist Center, 10002 Synott Rd.), a giant gold pyramid as worship space (Unity of Houston, 2929 Unity Dr.), an Italian fortress complete with enormous Ionic columns (Tempietto Zeni, 5420 Floyd St.), and…we’ll just stop there.

R is for Ranch Houses

Think Brady Bunch, not Little House on the Prairie. Known for their long and low profiles, ranchers, often made of brick or stone, became the norm as construction started on homes in Houston areas that, at the time, counted as suburbia—Glenbrook Valley, Spring Branch, and Garden Oaks/Oak Forest—in the decades following World War II. Boasting picture windows, sprawling single-story floorplans, family-friendly backyards, and attached garages, many are authentically mid-century mod. These days they’re on the rise again, with some homeowners choosing to outfit them in retro refurbishments.

Image: Christopher Vela

S is for Strip Malls

On any block, in any hood, Sharpstown to River Oaks,

Frequented by everyone from broke to bougie folks.

So similar in layout that you wonder if they’re cloning,

Plunked anywhere and everywhere all thanks to lack of zoning.

Plentiful and unassuming, heart of urban sprawl,

Around these parts there’s more than 20,000, after all.

Pretty? No, of course not; they leave much to be desired,

With neon signs and parking lots where shady stuff’s transpired.

But varied, yes, and useful, too, much more than meets the eye,

Hidden gems and low-key sites worth more than a drive-by.

Find cuisine from ’round the world—and it’s authentic (duh),

Like Tex-Mex, dim sum, barbecue, a steaming bowl of pho.

Stop in for a brow wax or have someone cut your hair,

Go for shaved ice, dumplings, or a trip to urgent care.

Tattoo shops, convenience stores, your favorite taco spot,

The strip mall, much like Houston, is just one big melting pot.

So scratch the surface of the sprawl and you might be surprised,

These little hubs are full of spunk, it should be emphasized.

A metaphor for what we are: diverse, authentic, gritty,

Don’t overlook the strip mall, it represents our city.

T is for Tear-Down Culture

In Houston, historic mansions, turn-of-the-century offices, and even actual pieces of art aren’t safe from being torn down to make way for something new. “We’ve lost so much of our architecture,” says Brian Malarkey, an executive vice president at Kirksey Architecture. “I think we really embraced back in the ’50s and ’60s this idea of a new city, and so that actually greased the wheels to encourage tearing some of these things down.”

This, more than anything, is the chink in Houston’s armor. “You go visit Barcelona, and different parts of Paris—they are older cities and they have learned to build the new around the old,” says Stephanie Burritt, co-managing director at Houston’s Gensler offices. “We are in such a baby stage that we don’t even have that much old to worry about building around, but it is important that we hang on to some of the old. What’s going to be that ‘wow’ piece in 100 years?”

U is for Ubiquitous

Apartment complexes | Self-storage facilities | Parking garages | Parking lots | High-rises that promise to honor the neighborhood's historical integrity | "Up-and-coming" neighborhoods | Stucco-faced suburban McMansions | Strip clubs | Wrecking balls

Mansfield House at 1802 Harvard

Image: Amy Kinkead

V is for Victorian

We have the Brits to thank for bringing elegant wrap-around porches, charming gables, and ornamental details across the pond for the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial. Today Victorian-era visions stand tall in Sixth Ward and the Heights, where you’ll find shining examples of the style such as the 1895 Milroy-Muller House and the 1899 Mansfield House, both on Harvard. But we’re especially partial to the big, blue beauty on the corner of Heights and 5th—that 1902 construction is home to Houstonia.

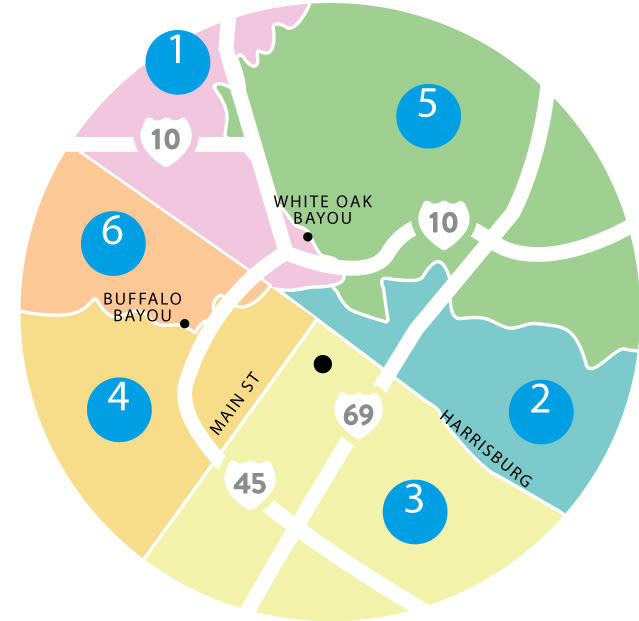

W is for Wards

Image: Amy Kinkead

When the Allen Brothers founded Houston in 1836, they divided the city into four political districts, with two more added a little later. Our six historic wards have been fighting to maintain their distinct cultures ever since—some with more success than others. What you’ll see today:

- First: Victorian homes and cottages, restored silos, and modern-day apartments, in the shadow of downtown’s massive towers.

- Second: A blend of Mexican-American culture and art-deco vestiges with former industrial sites-turned-lofts.

- Third: Some authentic and affordable housing, anyway, blending old with new, thanks to the efforts of the city and groups like Project Row Houses.

- Fourth: Only a few remaining shotgun houses and original brick-paved roads, built when freed slaves settled historic Freedman’s Town, mixed in with newer Montrose and Midtown structures.

- Fifth: Some boarded structures, but also plenty of recent construction, which began in the early 2000s with help from the Fifth Ward Community Development Corporation, bringing new residential projects and the restoration of the historic DeLuxe Theater.

- Sixth: A good number of original 19th- and early-20th-century homes, with the largest concentration of Victorians in Houston; this ward was the first to be designated as historic, back in 1978.

X is for X-Factor

We asked four local architects: What is the city’s x-factor?

It’s a supportive environment for risk. Part of that is the size of the city—you don’t need everybody to like it, you just need enough people to like it.

—Jesse Hager, Content Architecture

We are the most international and culturally diverse city in the country, not just in Texas. I think that does express itself in our architecture. Houston is so open to other ideas.

—Bob Inaba, Kirksey

If you’re thinking about Austin, you have a certain mental picture. You think about Dallas, you have a mental picture. But when you think about Houston, it’s not just one picture. There’s so many different things going on; the culture is so unique. I think that does affect the design zeitgeist, if you will, in the city.

—Brian Malarkey, Kirksey

It is kind of the wild west of architecture. Sometimes that creates chaos, but it’s a really interesting hodgepodge chaos. When people come here, it’s like they have never seen anything like it before. It is almost like an evolving art piece.

—Jake Donaldson, Method Architecture

Image: Amy Kinkead

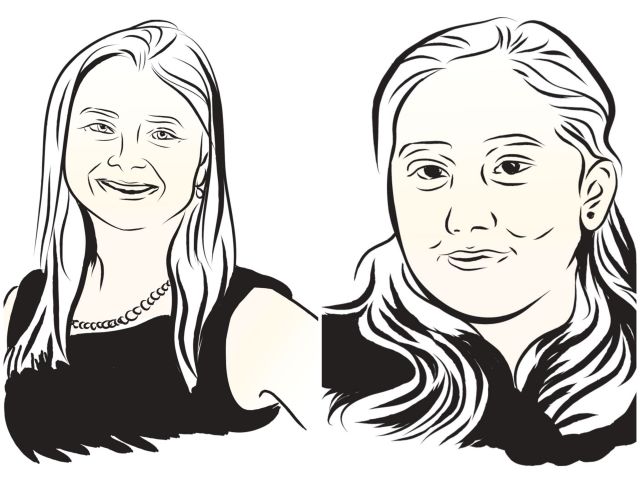

Y is for Youth

Kirksey Architecture hired the state’s youngest licensed architect in 2015, bringing on then-24-year-old native Houstonian Megan Tegethoff. Then last April, the firm topped itself by recruiting her fellow UH alumna, Altair Galgana-Wood, who beat her record by 18 weeks. “I was excited that, one, it was another woman that was driven and wanted to come out on top,” says Tegethoff. “And to have someone at Kirksey, that was like a double whammy.”

Zone D'Erotica stands in stark contrast to the Galleria.

Image: Google Earth

Z is for Zoning, Lack Thereof

It may seem ordinary to us, but our architectural disorder is not normal. We lack a zoning ordinance despite five separate attempts to pass one, the last of which was in 1993. This is why you can find a single-family home sandwiched between a bar and a self-storage facility, a strip mall next to a manufacturing warehouse, a crematorium next to a townhouse. Some find this free-for-all to be invigorating; others find it frustrating. There’s certainly a belief here that “chaos can be profitable,” explains Rice architectural historian and AIA Houston Architecture Guide author Stephen Fox, adding, “Houstonians don’t want someone else telling them what to do.”