Could Solar Power Ever Catch up to Oil and Gas in Houston?

Joey Romano, at his solar farm in Sealy

Image: Max Burkhalter

The Little Utility

A Montrose couple develops “farm-to-market” solar power.

On 12 acres of grassland they stand, all 15,000 of them, roasting in the late-August sun. The panels are deep navy, a blanket of elegant gadgetry mounted on symmetrical steel poles, four feet high and dozens long. They click and buzz every so often, gently rotating a few degrees this way or that, in search of UV rays falling from the sky. Somehow, the machinery looks soft and inviting, like a natural outgrowth of the landscape itself. A white horse grazes on the property next door, paying no mind.

Joey and Nicole Romano pull up in their sedan, baby seat strapped in the back. He pops out first, wearing khakis and boat shoes, a coffee stain dotting his blue oxford shirt. He’s 34, with wavy brown hair and a wide smile. “It’s always an accomplishment when we get out of the house, and get organized by a certain time,” he says, pointing to his freckled wife and their 6-month-old daughter, Camilla, now adorably secured in a Babybjörn. “We are knee-deep in figuring it all out.”

Nicole Romano, Local Sun's communications specialist

Image: Max Burkhalter

Like a growing number of Houston energy entrepreneurs, the Romanos are on a mission to crack the puzzle that is solar, Texas’s most tantalizing untapped renewable resource. Of the 72,000 megawatts of power pulsing through the state’s grid, a measly 0.7 percent of it is currently pulled from solar panels. Our installed capacity is equal to that of New Mexico’s, a western neighbor with 25 million fewer residents and substantially less open land. And here in Houston, the so-called energy capital of the world, just 2,000 home and business owners have slapped panels onto their roofs, opting to generate their own electricity. This, in a city with over 200 sunny days a year.

Joey walks down a gravel path and unlocks a steel gate. The panels fan out ahead of him. Local Sun—this “farm-to-market” solar project—opened just over a year ago, in February, during the first week of Camilla’s young life. It sits adjacent to a two-lane road in Sealy, with a complicated rural address that reads like nautical coordinates. The Romanos’ first challenge was finding a plot they could afford, one that was close to existing CenterPoint transmission lines and that couldn’t otherwise be put to better use. They hit the jackpot out on the coastal plains, 50 miles due west of Houston, over the Brazos River and down from a Wal-Mart distribution center. “If we were really ambitious, we’d get some type of livestock out here, to work the grass,” Joey says. “We like goats, but they chew through the wires.”

Joey was raised around energy; his father worked for the Zilkha family, first in oil and then in wind, eventually as Chief Financial Officer at Zilkha Energy Company. Nicole is a communications specialist who helps her husband sell their new venture. They’ve got their own experience in renewables—developing solar-powered shipping containers and a 14-unit, sustainable apartment building, in Montrose—but not quite at this scale.

The farm essentially operates as a tiny utility, pumping out 1.5 megawatts of solar directly onto the Houston load zone, enough to light up 300 area homes. To access it, customers sign up for electricity with The Woodlands–based MP2 Energy, the Romanos’ exclusive partner. There are no upfront costs or cancellation fees, and the price (7.3 cents per kilowatt hour, plus delivery fees) is competitive with existing renewable plans, if marginally higher than rates offered by mainstream retailers.

Their primary target is the Houstonian who can’t commit to an expensive, unwieldy rooftop installation but who believes in climate change, and who desires to see, up close, the transformative process by which their iPhones are charged, from sunlight to outlet. Perhaps it’s no surprise that Nicole stormed crunchy farmers markets for some of her earliest marketing blitzes. “It’s our job to make sure that when people do sign up,” Joey says, “they have 40 panels that are out here working for them.”

Getting the enterprise up and running on schedule was hectic. Some 50 people were in Sealy during construction, pile-driving posts into soggy soil, snapping panel after panel into place, laying a Kinder Morgan pipeline, stringing tangled wires. The whole job cost $3 million. And they’d love to build more just like it. Texas is on the precipice of a solar explosion, industry experts increasingly believe, and a small community of entrepreneurs like the Romanos are figuring out, day-by-day and project-by-project, how best to capitalize.

The couple passes their two inverter boxes, white and whizzing with DANGER stickers plastered on multiple sides. For a shady respite, they duck under a row of nearby panels. Joey will give tours of Local Sun to practically anyone who asks, at any time—he’s proud of the ingenuity, and enthusiastic about the future. “That’s the point of all of this,” he says. “Doing things that make us a living, and at night, we can go to bed feeling like we are pushing the ball forward.” If the economics prove out, they could oversee a satellite of solar farms, powering a few hundred or thousand households at a time, leaving the region a little cleaner than they found it, and their wallets a little flusher in the process.

Over his shoulder, Camilla looks warm, but content. Like the equipment overhead, she barely makes a noise.

A TSO crew attaches solar panels to a roof.

Image: Max Burkhalter

The Old Guard

At one of Houston’s first solar firms, business is booming.

Cal Morton shimmies into the alley behind Texas Solar Outfitters (TSO), on Shepherd just south of Washington, to peek at his company’s electricity meter. He loves to come out back and track how little dirty energy this solar-equipped warehouse requires, even on a steamy July afternoon, a hot month in a hot year. He leans in, squints at the small numbers, and shakes his bald head in deadpanned disgust: “Oh, that’s a bummer—we’re still barely pulling power off the grid right now. I’m going to go shut that air conditioner off.”

TSO is one of Houston’s most established solar companies, a member of the old guard, which is to say it opened in 2011. Their facility has the feel of a classy auto shop. A copy of Power Magazine sits on an end table in the narrow lobby, underneath aerial photos of the firm’s handiwork, like the two-megawatt buildout affixed to DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center. With 24 staffers, they’ve completed about 300 residential installations in the Houston area to date, plus some commercial jobs, doubling the volume of their business every year.

Cal Morton, inside the Texas Solar Outfitters warehouse

Image: Max Burkhalter

Now 53, Morton has the bearing of a laid-back rancher. His dog Biscuit, “head of security,” naps underneath his dusty wooden desk. He joined TSO a year after it launched, as a sales and marketing executive. Having worked in finance and mobile app development, both in the United Kingdom and the States, he’d reached an age where he felt compelled to pick a field that would motivate him until retirement. That meant building things that “people can see,” and that he regarded as demonstrably “good.”

The environmental benefits of solar were never in doubt. But only recently, as Morton knows full well, have the economics started to make sense. Renewables run into problems when the prices of their entrenched competitors are cheap. Because natural gas is so abundant in Texas, the cost of traditional power generation here is currently low; only seven states paid less, on average, in July of last year. And while the Texas state legislature isn’t necessarily hostile to solar, lawmakers haven’t gone out of their way to incentivize its growth, either: Texas has a fairly unambitious renewable-energy standard, no state tax credits for solar installation, and no net metering, a common policy that allows customers to sell back to the grid their unused power.

In an energy market where regulators have no legitimate control over what type of plants get built, price alone determines what flows into the Texas grid. “If a technology can’t compete based on cost, then for the most part developers aren’t going to invest in it,” says Warren Lasher, senior director of systems planning for the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT).

Lasher, though, has started to see the figures shift in his long-range planning studies. The cost to manufacture a solar panel, once exorbitant, is sinking quickly, by as much as 70 percent since 2010 by some estimates, and with no end in sight. As in the days when personal computers started to attract mainstream users, price reductions and sales volume are directly linked. “We’re really reaching significant scale here,” says Sean Gallagher, vice president of state affairs for the Solar Energy Industries Association, a trade group. “Along with that scale has come billions of dollars of investment.”

A handful of municipal utilities in Texas, namely Austin and San Antonio, have already dived in, head-first—two years ago, Austin Energy famously finalized a contract to purchase 150 megawatts for less than the average cost of natural gas. Meanwhile, in November 2015, the Houston City Council approved its own 20-year contract to purchase 30 megawatts, about 7 percent of the city’s annual electricity needs. Commercial utilities will start to follow, from community sites like the Romanos on up. Same with homeowners interested in distributed generation, a jargony term for small power systems like rooftop solar, the type of clients that TSO serves.

ERCOT predicts that 17 percent of the state’s power will derive from the sun by 2031, with no additional coal or natural gas sources added. And if the trends don’t shift too dramatically, analysts at UBS expect solar capacity to triple nationally over the next decade, as wind did before it, eventually becoming “the default technology of the future.”

TSO’s warehouse is attached to Morton’s office. An arcane inventory of clamps and coiled wires rest on massive shelves along two walls. Around the way is an ersatz roof a few feet off the ground, shingled and sloped, on which the technicians train. One young employee, wearing an orange TSO-brand athletic shirt, straps a few panels into the bed of a red pickup, en route to a new job site.

A home system can run anywhere from $12,000 to $30,000. But while a traditional utility can’t guarantee what their power prices will be next year, much less two decades from now—historically, they’ve risen steadily—the fuel that home panels collect is permanently free, so long as the sun rises in the east. Morton is a true believer. Even the meetings that don’t lead to a sale are rewarding, because he’s able to proselytize for a few minutes about the revolution he feels is just getting underway.

“You put solar panels up, connect that to a variable-speed pump, and boom,” he says. “It’s cheap! Reliable. Lasts 30 years. No gears, no grease. The other stuff is just sunshine that was buried 500 million years ago, that you have to go dig up and burn.”

To prove his point, he hops into his SUV and scoots down Shepherd toward K+N Sales, a neighboring appliance wholesaler. When owner Ed Bajorek purchased 101 kilowatts worth of panels for his metal roof, in 2013, friends and colleagues were dumbstruck. “They know him as a penny-pincher,” Morton remembers. “Then they thought, ‘S**t, if Ed did it!’”

Across I-10, Morton spots Lonestar Orthopedics, its own panels barely perceptible, but unmistakably gleaming in the midday haze. He’d stopped in there one day and left a business card, no expectations. It took a year or more to complete the negotiations. “They didn’t call up and say, ‘Hey, I’d like you to come over and spend $250,000 on solar—who do I write the check out to?’ You have to temper your enthusiasm.”

Some of TSO’s best customers, ironically, work in oil and gas. It’s not that they’re atoning for ecological sins, necessarily. Most, Morton finds, are just energy experts with disposable income and a nose for deals. “It’s nice that solar is green—that helps in their decision,” he says. “But this is Houston, Texas! If we only sold to tree huggers, we’d have run out of them a long time ago.”

Sunnova CEO John Berger

Image: Max Burkhalter

The New Power Company

Bringing solar to the masses, right from Greenway Plaza.

The walls in Sunnova’s Greenway Plaza headquarters might be painted orange, and the conference rooms might be named for an assortment of sun gods (Apollo, Ra). In press releases, the marketing team might brag about their ranking as the largest private residential solar company in the United States, and the fourth largest, period. But Sunnova executives would like to make one thing absolutely, positively clear: This is not some Patagonia-clad, utopian enterprise. “At the end of the day, we’re a power company,” says CFO Jordan Kozar, in a typical refrain. “We sell electrons to customers.”

This distinction, subtle as it may seem, is crucial to Sunnova’s identity, and the manner by which they’ve positioned themselves in the increasingly competitive renewables marketplace. It’s a Houston-based firm committed to solar because there’s cash to be made. “Contrarian” is one of the executives’ favorite adjectives.

John Berger, Sunnova’s co-founder and CEO, is a tall man with coiffed brown hair and gleaming white teeth. It’s easy to imagine the 43-year-old hobnobbing at the Petroleum Club, maybe catching an Aggies game in a luxury suite at Kyle Field. A Bryan native, Berger got his start on the power-trading desk at Enron, before business school at Harvard and a stint running a venture capital firm. In 2007, with family friend Jordan Frugé, he opened an energy-efficiency products company called Standard Renewable Energy. (Tagline: Review, Reduce, Renew.)

That firm was acquired by GridPoint, who, according to Frugé, “didn’t know what they wanted to do, but they knew they liked what we were doing.” Their next operation, SunCap Financial, was purchased again, this time by NRG, in March 2012. Berger and Frugé replicated that company’s model when they created Sunnova, nine months after that merger.

How does it work? Sunnova installs solar systems on customers’ roofs with no money down. They retain ownership of the actual equipment, servicing it for the duration of the contract, often 25 years. The mechanical work is outsourced to one of Sunnova’s 120 partners, independent outfits, not unlike TSO, with electrical expertise and knowledge of their specific region. All the homeowner has to do is agree to buy clean electricity from Sunnova at a predetermined price, at or below the market rate charged by conventional utilities.

The goal is to minimize the hassle and risk of distributed generation, without losing the advantages. “This is the way to bring solar to the mass-market,” says Lynda Attaway, Sunnova’s chief strategy officer. “It’s not to sell them a $50,000 product, but to sell them delivered electricity. They don’t have to think about maintaining a power plant.”

Around 235 employees work for the firm, spread across portions of three high-rise floors. A Google campus it is not. There’s no personal chef, only a break room with vending machines. The ceilings are low, the cubicles perfectly ordinary. Bosses are sprinkled in among the hordes; Berger squeezes himself low into his chair, perennially fielding calls with what little privacy his office-less existence allows. “It’s not wide-eyed,” says Kris Hillstrand, another executive.

Neither is Sunnova’s financial strategy. While the private company is wary about disclosure, its customer base is in the tens of thousands. The balance sheet is not exotic or over-leveraged—in the first quarter of 2016, they posted positive adjusted earnings. “We have a much more conservative view on the world, more focused on the fundamentals of the business,” Berger says, “whereas the West Coast [renewable] firms are much more, go-go-go, grow-grow-grow, at any cost. That works for a while. And then when it doesn’t work, it’s pretty bad.”

Kozar, a former investment banker who focused primarily on midstream oil and gas companies, has raised an impressive $1.5 billion in capital so far. His elevator pitch is straightforward: In an era of sinking solar technology costs, and in the markets that Sunnova judiciously enters (17 states, along with Guam, Puerto Rico and portions of the Northern Mariana Islands), the dollars finally add up.

As recently as five years ago in Houston, Berger says, “you could put the number of pro-solar people in a phone booth and you’d have had space left over. It was definitely like, ‘What are you doing? Did you get lost? Are you okay?’” Still, the city provides an ambitious renewable company with undeniable advantages: an unparalleled cluster of energy and infrastructure experts from which to draw talent, a reasonable cost of living, distance from the bubble of potential competitors.

Michael Skelly is president of Clean Line Energy Partners, a 56-person Houston-based business with plans to lay down $9 billion worth of transmission lines, connecting the windiest and sunniest areas of the country to those lacking access to clean sources. He can’t think of a better city to call home. “People don’t come up to me at parties and say, ‘Why are you doing renewable energy when you could be poking holes in the ground?’ Maybe they say that when I’m not around, I don’t know. But ours are audacious projects, and people in Houston appreciate that.”

The downturn in the hydrocarbon sector hasn’t hurt, either. Kozar has taken several calls in recent months from old midstream colleagues, all of which come in the form of a friendly catch-up. Most end with inquiries about potential Sunnova job openings. “It’s exciting,” he says, “to see people opening their eyes to what this really is.”

Kris Hillstrand sits on the seventh floor, adjacent to Sunnova’s customer operations department, which he oversees, and which functions like an in-house call center. Young people in headsets occupy a long stretch of desks from the pre-dawn hours until midnight, answering questions from anxious or confused clients. As the company expands its reach into more territories, the volume of queries will necessarily rise. Sometimes, Hillstrand likes to stay late, take off his noise-canceling headphones, and eavesdrop on the conversations. It’s edifying to find out what’s important to people generating electricity for the first time, what they are learning.

“There was a time when we were all highly attuned to weather cycles and seasonality. You understood the peaks and valleys of solar production,” he says. “We’ve kind of divorced from that as a society, as we moved away from renewable and into centralized generation and fossil generation. This brings people back a little bit.”

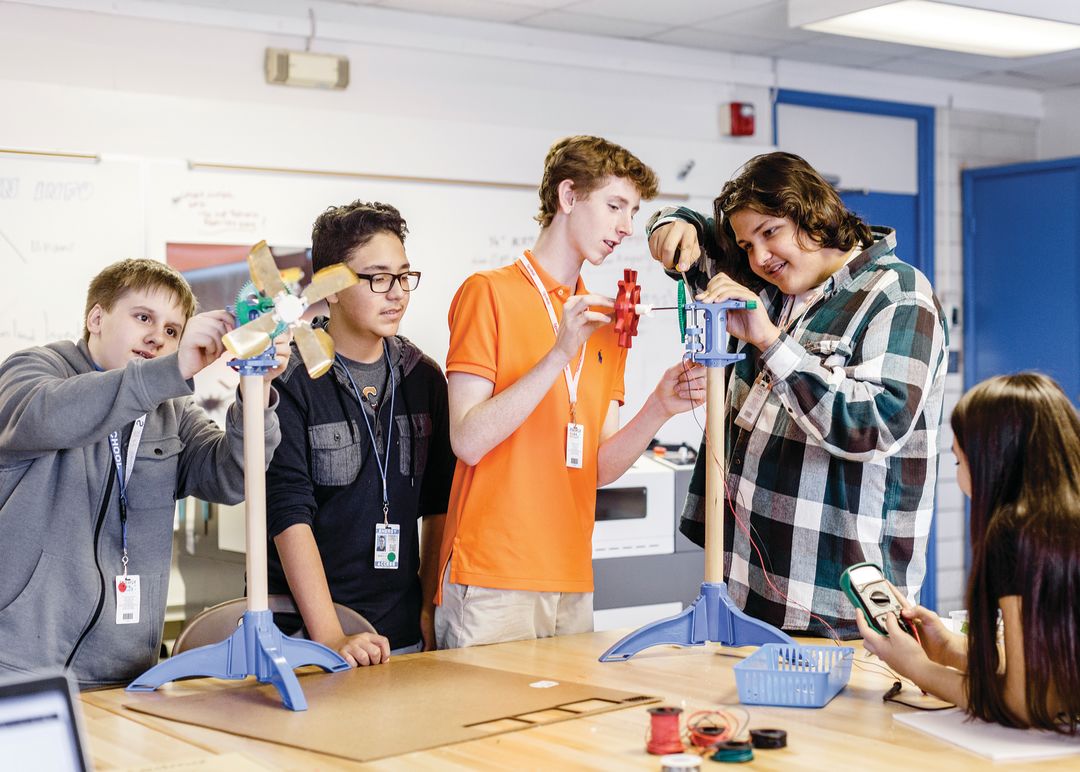

Students tinker with renewables at HISD's Energy Institute.

Image: Max Burkhalter

The Future

These Houston teens are studying the energy of tomorrow.

The semester has just kicked off at HISD’s Energy Institute High School, and sophomore Michael Sanchez is eager to share his work. Short and slender, with bright green Nike sneakers and braces to match, Sanchez loads up a presentation on an interactive classroom projection screen. A small audience—renewable energy teacher Barbara Finberg, principal Lori Lambropoulos, and three incoming freshmen—adjust its chairs to watch. Sanchez pauses a beat to collect himself: “I’ll show you everything you need to see,” he says.

In his first year at Energy, the nation’s only full-STEM magnet school with an energy emphasis, Sanchez and his classmates completed a project called Green Energy Machines. “We were assigned a country, one that’s currently suffering from energy poverty, and we were told to create a set of blades that attach to a hydroelectric or wind turbine.” He flicks through a few slides, explaining how different teams employed different strategies, molding brass or fiddling with the school’s 3-D printer. One model sits on the table in front of the other students, a beautiful little object with a green node on top, like a fancy flower. “This one is a very sophisticated print,” he says, commanding the floor with confidence. “It’s actually incredible.”

At the end of the semester, Finberg brought in a huge fan, and the kids tested their prototypes to see how much voltage each produced. The average output was about three units. Sanchez’s group, using a plane propeller as inspiration, blasted out nine. “Someone topped off at 12 volts,” Finberg remembers, “and I thought it was going to take off, it was going so fast.”

Energy, which opened in 2013, is an atypical high school. Its temporary home is a cramped two-story building on Sampson, a few miles south of downtown, identifiable by the cartoon graphics (an offshore oil rig, a set of mechanical gears, a wind turbine) glued onto the faded brick facade. A sign off the main office—Inspiring the Next Generation of Energy Leaders—broadcasts the administration’s intentions.

For the 705 enrolled students, the curriculum is centered around project-based learning, multi-week blocks in which kids investigate a given problem, participate in workshops around the topic, and formally present potential solutions to their peers. Teachers follow an engineering design process as opposed to a typical lesson plan, and the staff leans on the expertise of its advisory board, 30 or 40 representatives from Houston’s energy industry, who judge contests and deliver thematic lectures. For the 200 spots in each class, Lambropoulos has received as many as 1,600 applications. “The kids that come here give up a lot,” she says. “They are not going to get the traditional cheerleading or football experience.”

Lambropoulos’s dad was a chemical engineer for 37 years, a buttoned-down type with pens perpetually stashed in his breast pocket. At Energy, she sees that quiet nerd stereotype falling away. “Kids get excited,” she says, “and it’s dynamic.” It’s taken her by surprise just how enthusiastic her students are about solar and wind. The topic of renewable energy shows up in classroom surveys and in casual conversations she overhears in the tiled halls. “I don’t have many students who bring up questions about oil and gas,” Finberg adds. “They want to know what’s next. They really want to know, ‘What’s the thing I need to be an expert in, in order to be a leader in this field?’”

Nicolette Beguerisse is a freshman, a polite young woman in a gray hoodie who dreams of attending MIT. Her school ID card, stuffed into an Exxon Mobil lanyard, hangs loosely around her neck. Beguerisse doesn’t have any family or friends in the energy business; she just loves math. When Lambropoulos asks her why she’s excited about Finberg’s renewable energy course, Beguerisse delivers a completely logical answer that might have horrified her Houston forbearers: “I would like to be part of the process that corrects the issues the petroleum industry has created.”

Their first task is to build a solar-power cell phone charger. In a tongue-in-cheek video prompt that Lambropoulos had previously recorded, she pleaded for help, warning her freshmen that their campus electric bills will one day “drive this school into the poorhouse!”

“So first,” Beguerisse says, “we have to learn the basics of engineering. Then we have to learn how to sketch out our idea. We need to know the cost of the bills from the school. We also need to know what materials we are going to use, and their cost.” One classmate was convinced he could restore batteries using potatoes; for their first assignment, they researched his hypothesis, determining it would take 267 spuds to power one house for one single hour. Maybe impractical, they concluded.

Sanchez, the wise sophomore, offers some friendly advice: “As you start building, you’ll start to realize that some things don’t work, or you’ll need to change the design a little. Don’t freak out!”

He turns to Michael Lopez, a freshman with slicked-backed hair and an Altoid addiction. “I really like the idea of renewable energy,” Lopez says, a huge grin spreading across his face. “You can use it, and keep using it, forever! Exponentially! It really is just amazing when you think about it."