Flood Waters and Unanswered Questions Remain for Frustrated Memorial Residents

Meryl Gregory's husband and sons in front of their Lakeside Estates home, which took on 10 inches of water.

Image: Courtesy of Meryl Gregory

Barry LaCoste and his family, like many Houstonians, relied on civilian rescuers to evacuate their Memorial Thicket subdivision when flood waters began to rise after Hurricane Harvey. Unlike other Houstonians, however, LaCoste's two-story home hadn't taken on any water during the days of torrential rains; his home was flooded when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began an overnight release of water from the Addicks and Barker reservoirs into Buffalo Bayou to avoid a failure of the dams' earthen levees.

"We thought we were safe," says LaCoste. "That’s the worst part."

Initial reports that night, Sunday, August 27, had said to only expect a few inches of flooding, but he and his wife quickly realized by the following Monday morning—less than 12 hours after their electricity was cut off by order of Mayor Sylvester Turner—that wasn't true. "With how fast it was rising, we had to do something," he says. "We had to get out. And they didn’t even issue an evacuation order at all by the time we left."

Waist-deep water, says LaCoste, "was literally flowing in the street like a river. There just weren’t enough official rescue people. It was extremely scary." Eventually, thanks to the help of strangers who ferried and later drove him, his wife, and their 2-year-old son to a Red Roof Inn at Highway 6 and I-10, LaCoste was able to book the hotel's very last room. Throughout the last-minute evacuation process, LaCoste wondered: Why didn't they receive any notice?

"Most of our neighbors didn’t know. It wasn’t on my TV. It wasn’t on our social sites. It wasn’t on my phone alerts, even though we got flood alerts every 15 minutes," he says. "That’s the biggest complaint from anyone I’ve heard; we weren’t given any time to save anything, weren’t given any warning."

Why was a sudden, overnight release necessary? Were the dams really in danger of failing? Why weren't mandatory evacuation notices issued for the entire affected area, rather than just homes that had already received minor flooding during the storm? Why wasn't the voluntary evacuation notice issued until September 1?

These are just a few of the unanswered questions lingering across Memorial and the Energy Corridor, as families like the LaCostes remain displaced and distressed and approximately 4,000 homes remain flooded.

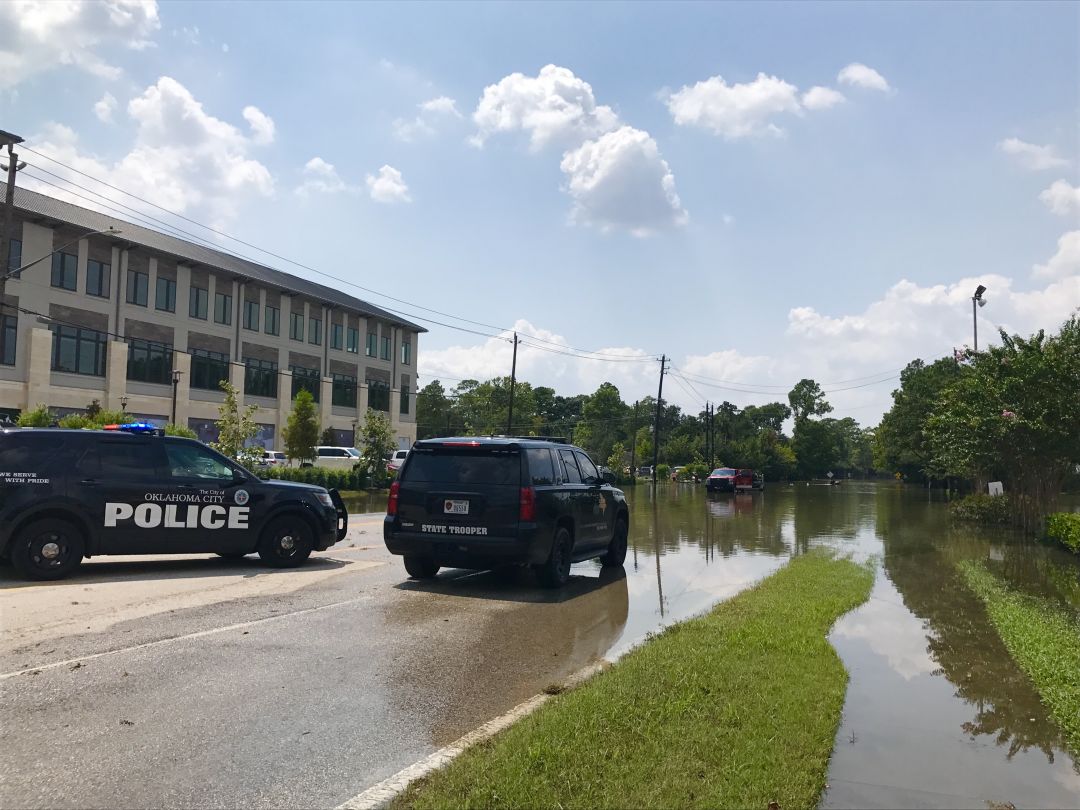

Police cars block access to flooded neighborhoods off Memorial Drive; many residents have been unable to return home for more than a few minutes.

Image: Katharine Shilcutt

This afternoon inside the Lakeside Estates home of Meryl Gregory, a 16-person crew from St. Cecilia Catholic Church helped tear out wood paneling and other ruined portions of the home she shares with her husband and three children. They were lucky enough to be rescued by a Houston Fire Department crew after receiving a mandatory evacuation notice on August 28, as their home had taken on a small amount of water during the worst of Harvey.

Yesterday, Gregory ferried her insurance adjuster to the house for his first glimpse of the devastation: 10 inches of standing water in a home that had never previously flooded—and all 10 inches due to the intentional flooding of Buffalo Bayou downstream from the reservoirs. The smell, she says, was so bad that her insurance agent gagged, trying to keep from vomiting as he documented the flooding.

"I am one of the lucky 20 percent that actually has flood insurance," says Gregory. "But the maximum amount that anybody can have is $250,000." Her contents were also insured at the max of $100,000, but their home is worth $700,000. "I can’t go anywhere else in this neighborhood and buy a home for $250,000," she says. Where will her family get the funds they need to rebuild or repurchase a new home? And how quickly will they burn through their cushion of emergency funds?

"I’ve got 16 people here in my house and I want to feed them," she says, "but I don’t know if I’m going to have money to do things. Before I wouldn’t have thought twice about bringing in 10 pizzas to feed people, but now I'm having to nickel and dime everything—everything counts. I can’t imagine people who are in a lesser economic bracket than we are. It’s overwhelming."

LaCoste is already feeling the stress of unknown financial loss too. Like many Houstonians hit by the oil and gas downturn, he was unemployed for two years before finally finding a new job in April. "We worked hard, we saved our money, we bought a nice house, had a nice emergency fund, which I used while I was unemployed for two years," he says, "so most of our emergency fund went to that."

Worse, he points out, are the untold numbers of other Houstonians in the same position: unemployed, and now without a home, without vehicles, without any clear path forward.

"People will be walking away from houses they just can’t afford—houses they’ve lived in for 20 years," says LaCoste. Like Gregory, he filed a claim with FEMA but has yet to hear anything in response from either that agency nor any others. "I would definitely like the government to step up and tell us if they’re going to help us or not. If we’re on our own, we’ll be on our own."

Flood waters over 16 feet deep covered the main lanes of Beltway 8 at Kimberley until yesterday.

Image: Katharine Shilcutt

FEMA expects more than 450,000 Houstonians to file for federal relief, though it's anyone's guess as to when the agency will be able to access and appraise the thousands of flooded-out homes in Memorial and the Energy Corridor. "September 15 is supposed to be the magical deadline when the bayou is back to its regular level," says Gregory, who's equally concerned about what FEMA's eventual response may be.

"What’s going to happen with all of these properties?" she asks. "Is FEMA going to condemn them?" What will happen to the thousands of oak and pine trees currently dying in flood waters? The roads that are developing sinkholes? The subsidence occurring around bridges throughout the neighborhoods that skirt both sides of Buffalo Bayou? The inevitable worsening of gridlock when Houston ISD and Spring Branch ISD resume classes for the semester?

"Nobody’s got any answers," she sighs. "Nobody knows what’s going to happen."

More than anything, Gregory says, she just wants to know how Houstonians will gain access to the millions of dollars being raised for hurricane relief. "I don’t want a lot," she says. "I just want something—a piece of the pie if it’s supposedly going to Harvey relief victims." But so far, answers to all of these questions are still up in the air.

For LaCoste, whose family has been taken in by his boss for now, the biggest concern right now is that so many factors are still unknown. The one and only time they've been back to their home was Thursday, August 31, when they were allowed 10 minutes to grab essentials; during their harried evacuation the previous Monday, they'd only been able to grab milk and a single toy for their toddler son.

The LaCostes still don't know when they'll be able to return, though—like Gregory—they're hoping September 15 will be the day they can finally begin to assess the amount of rebuilding ahead of them.

"It’s gonna look like a disaster area," says LaCoste, a native of southern Louisiana. "I’ve seen parts of New Orleans six months to a year after Katrina and the recovery is just incredibly slow when you get this much water. How are we going to rebuild? It’s going to take money for people to start rebuilding things, and money through the recovery channels will be very slow going. It’s going to be tough."

Even rebuilding, he says, seems so far away as to be ridiculous. There are more pressing short-term concerns: "How are we even going to make our house livable?" he asks.

Barry LaCoste's Memorial Thicket subdivision remains flooded. He hopes to gain access to his family's home sometime in the next 10 days.

Image: Courtesy of Barry LaCoste

The same Thursday he was allowed back to his house for a brief window of time, LaCoste spotted U.S. Representative John Culberson getting his own first-hand look at the devastation within his congressional district. But outside of this brief interaction and a neighborhood meeting attended by Greg Travis, the Houston city councilman for District G, LaCoste says communication from local, state and federal agencies has been extremely limited in scope and information.

Travis will be presenting a Town Hall meeting on Saturday, September 9 with representatives from FEMA, CenterPoint, the public works and solid waste departments, and the HPD and HFD, during which many residents can expect to begin asking their biggest questions. Travis also went on a tour of affected Memorial neighborhoods yesterday afternoon with Mayor Turner himself, though residents are still waiting to see what immediate assistance that will bring.

"No one in our area has seen any tangible help," he says. "Right now we’re talking financial assistance. We'd love a plan, an idea of how it’s going, and how we’re going to get back to our homes. Are we going to rebuild or are we going to abandon them?"

Lacking answers, a frustrated LaCoste penned a blog post on LinkedIn on September 4 he titled "Deliberately Flooded—Our Hurricane Harvey Story." It's since received over 130,000 views, and generated thousands of comments and responses.

"I’ve gotten so many calls and private messages from people who say this is their story," says LaCoste. "Our entire neighborhood wants to get back in their homes, to figure out a way to rebuild. But there's a lot of confusion about what comes next."